Landing Craft Pilot Faced Heavy Fire in Pacific Battles

Mike O’Connor as a young sailor in the U.S. Navy during WWII.

Mike O’Connor piloted a Higgins boat throughout the Pacific in World War II, serving on USS Elmore (APA-42)

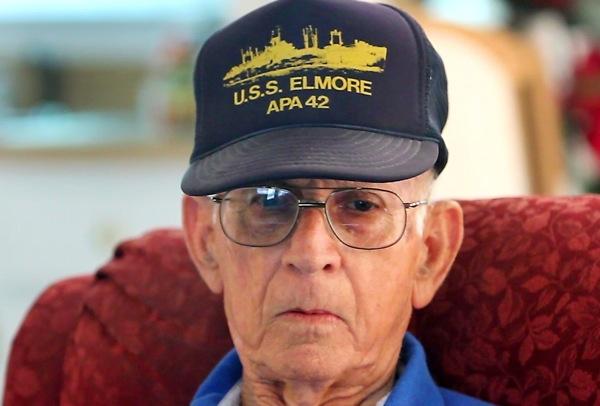

Sometimes Mike O’Connor, 86, has a “smell memory” that takes him back decades.

“Every once in a while, I smell those blowers blowing” fumes from the engines of a landing craft, the Lakeland resident said.

O’Connor piloted a specialized type of landing craft, known as a Higgins boat, throughout the Pacific in World War II under heavy fire while delivering Marines and soldiers to occupied beach heads.

The boats carried 36 troops and a crew of four and the ramp opened in the front, giving the enemy a clear shot at what was inside.

“They were plywood boats and it was easy, in those waters, to knock holes in them,” he said. “And then you’d have to haul them out, haul them up and repair them on ship. They gave me a jeep (to land) in Guam. I couldn’t get the boat up to the shore, so we opened the front and the water came in and swamped it.

“We hid under a drag line on shore until the shooting from the Japanese died down,” O’Connor recalled, “then pumped the water out and got a tow by the ship.”

O’Connor joined the Navy on Dec. 8, 1942, and was sent to boot camp in Bainbridge, Md., where he saw his first snow. It was a shock to a kid who had known only tropical and subtropical climates.

O’Connor and his three sisters were born in Honduras. Their father, Michael Ronald O’Connor, had gone there from the States to be a train engineer for United Fruit Company. He met and married their mother, Petrona, who traced her ancestry back to the Mayan Indians.

The elder O’Connor died when Mike was 13. The children had been in American schools and had lived in an American complex. Their mother moved them to Tampa after their father’s death so they could continue to be schooled in English and could live under better conditions.

Mike O’Connor’s service tag he wore while serving in the Navy during WWII.

Young O’Connor’s American roots ran deep, however.

“When the Japanese hit Pearl Harbor, I didn’t know where that was. Neither did many others, but we knew they had hit Americans and we wanted revenge,” he said.

The Navy was an easy choice.

“I love the ocean and I love going on ships, he said.

After basic training, he was sent to Fort Pierce for advanced training in landing the Higgins boats. When officers discovered that O’Connor had carpentry experience, they offered to let him stay permanently in Fort Pierce, working in the boat shop.

But what 19-year-old would want to stay behind?

“I said, ‘No, I want to see some action,’” he said.

He got his wish many times over.

He was assigned to the USS Elmore, a Bayfield-class attack transport that delivered troops on Pacific battlefields with the use of landing craft.

Mike O’Connor served in the Pacific on the U.S.S. Elmore during WWII.

His first experience in battle was landing troops at Enewetak, an island in the Marshall Islands.

“That one was kind of rough,” he said.

“We didn’t have the line (of ships) back far enough. My blood felt like it was boiling, I was so scared,” he said.

“We headed in to an old dock. There was a large light pole at the end and there was a sniper in there. He was shooting down at us and went unnoticed for a while because of so much machine gun fire. The Marines then saw him and got him,” O’Connor said.

The landing crafts, several abreast, kept running continuously from the transport to the shore, taking troops in or taking in ammunition or gas for the vehicles.

“When you went in there, you never knew which would be the worst; the first wave (of troops being unloaded) or the fifth wave,” he said, referring to one Japanese tactic of sometimes waiting until all the troops had been delivered before opening their counterattack.

Mike O’Connor’s medals from serving in the Navy during WWII.

But there were some times between invasion runs when the ships would pull into the Fiji Islands for a short respite. Sailors and Marines were given tickets for beer or treats.

“I didn’t drink, so I would trade my beer tickets for ice cream,” O’Connor said with a laugh. “Some of those folks would drink a lot of beer. I’d eat a lot of ice cream.”

The next invasion moving along the Pacific was Guam, and the practice of staying out in the harbor away from the armed transports became too dangerous.

“I cranked up the boat and we went out to sea with maybe three or four other boats and we tied each together for the night. When we woke up the next morning, there was no land in sight; the tide had carried us way out.”

With maps and compasses in the boats, they made it back safely.

In late 1944, the American forces began to take back the Philippines from the Japanese.

The first landing was in the Leyte Gulf.

Adm. William “Bull” Halsey had been lured with his carriers to the North by a Japanese decoy fleet, leaving behind the destroyers and cruisers and the transport ships.

The combat ships then faced off against a Japanese fleet bent on stopping the landings.

“If they (Japanese ships) had gone after the transports, it would have been a disaster, ” O’Connor said.

In May 1945, the battle for Okinawa began and O’Connor’s boat was among three picked to take Navy frogmen in close to shore to blow up coastline defenses.

“My crew wouldn’t speak to me for a long time,” he said. “They thought I had volunteered the boat for the job.”

Mike O’Connor’s Boatswains Pipe from his Navy service during WWII.

It was one of the time when O’Connor heard the orders he didn’t want to hear.

“They’d say, ‘Take out all the stuff you wouldn’t want you family to see and leave your key in your locker,’” he said.

The meaning was obvious: The key was left in the locker so if the sailor didn’t return, his personal items could be returned to his family.

In one of the runs on the beach there, he was in formation and could not turn left or right.

“We were headed straight for a pillbox (a concrete machine gun bunker) and there was no way I could move out of its path. Fortunately, it was not occupied,” he said.

Shortly after the successful Okinawa battles, the transport on which O’Connor served was damaged in a typhoon.

The Elmore returned to the U.S. for repairs and was there when the Japanese surrendered.

Mike O’Connor’s ball cap with his ship, the U.S.S. Elmore, which he served with in the Navy during WWII.

The war was over for O’Connor, but not his service in the Navy.

“I was 19 when I joined and I didn’t know that if you joined the reserves, you signed up for four years, but regular the Navy that I signed up for was longer. They hooked me for six years,” he said.

He did not get out of the Navy until December 1948, but he did travel. He even went to Antarctica on a ship carrying famed Navy explorer Adm. Richard E. Byrd.

He came back to Tampa in December of 1948 and found that Ann, a little girl in his old neighborhood, had grown up. They fell in love and married the next year, in 1949.

With his carpentry skills, O’Connor built homes in the postwar housing boom. But in 1951, he and Ann moved to Lakeland, where he took a job as a trainman for Atlantic Coastline Railroad. He was a conductor for more than 30 years and retired in 1985.

Retirement didn’t sit well for Mike O’Connor. To keep busy, he worked for a laundry and then for Walmart, not really retiring until the late 1990s, he said.

The couple had two sons born and raised in Lakeland: Ron, who still lives in Lakeland, and Glenn, who lives in Ocala. A year ago, Ann died. The O’Connors had been married almost 60 years.

“I’m proud to have served when I did. A lot of teenage boys were quitting school and joining up. And a lot of them didn’t come back, but the good Lord was looking after me,” he said.

Mike O’Connor talks about his days serving in the Navy during WWII.

Source: The Ledger (Lakeland, FL)

By Bill Rufty

May 23, 2010

Want to learn more?

Pictured at left: An LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) or “Higgins boat” unloading troops. They served everywhere — from the wind-swept coastlines of Northern France to the far-flung tropical shores of the Pacific — ultimately changing the very nature of amphibious warfare. The 'driver' for these boats was called a "coxswain" (pronounced 'Cox N.' That is what Mike O'Connor did as part of Elmore's crew. Click to zoom.