The Story of Hill 522

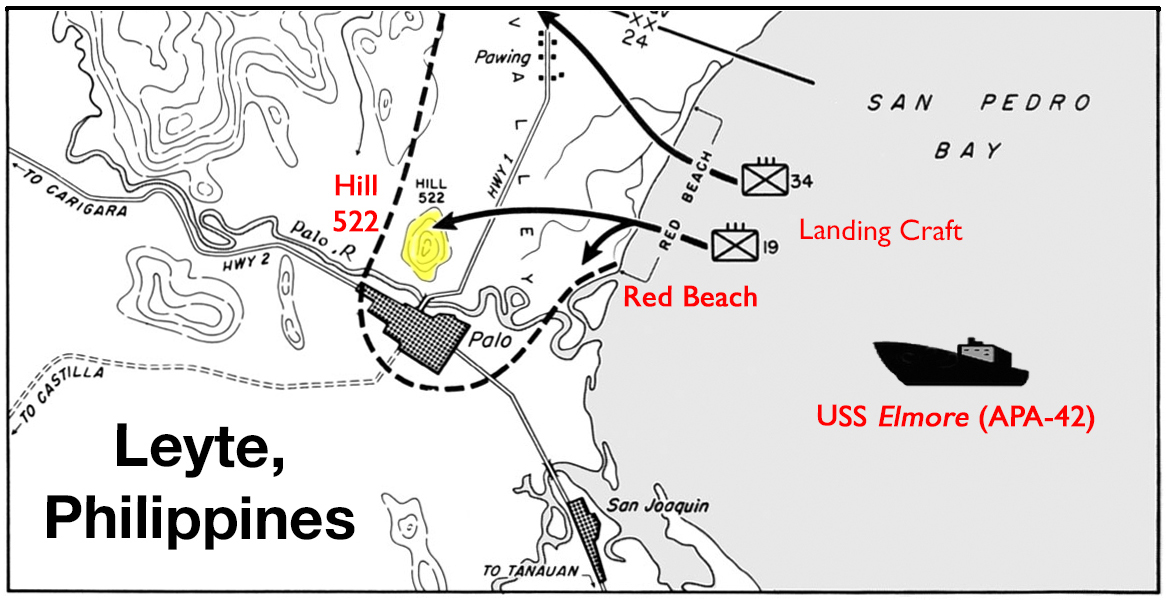

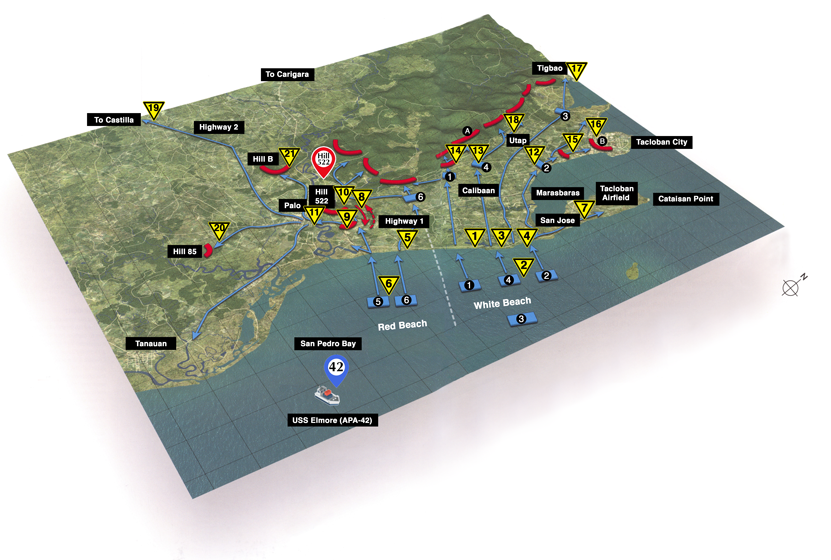

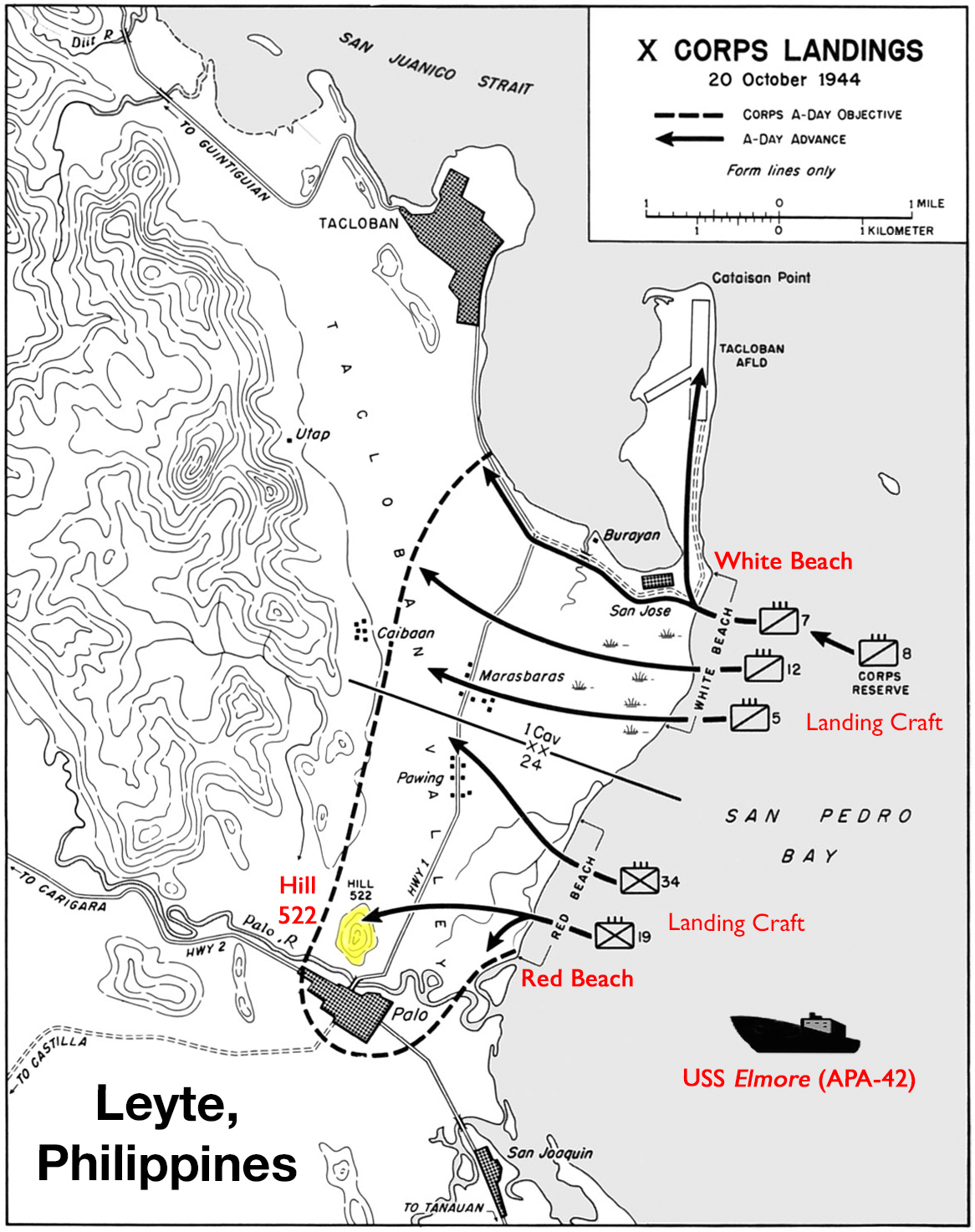

General Douglas MacArthur, in his unrelenting quest to liberate the Philippines after four years of Japanese occupation, landed at Palo “Red” Beach, Leyte, on 20 October 1944. USS Elmore (APA-42) was there at Red Beach, landing troops of the U.S. Army’s 19th Infantry, 3rd Battalion, several hours ahead of MacArthur’s triumphant return. The Japanese defenders were ready, having built a fortress to repel the invaders at Hill 522, just inland from Red Beach, alongside the town of Palo.

Background

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of about 7,641 islands spanning more than 300,000 square kilometers of territory. Japan had conquered the Philippines in 1942. Controlling it was vital for Japan's survival in World War II because it commanded sea routes to Borneo and Sumatra by which the vital war materials of rubber and petroleum were shipped to Japan.

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, there was an extensive native resistance movement which opposed the Japanese and their collaborators with active underground and guerrilla activity. The guerrillas were so effective that the Japanese Empire only controlled 12 out of 48 provinces. During the occupation, many Filipino soldiers and guerrillas never lost hope of the United States returning. Their objective was to both continue the fight against the Japanese and prepare for the return of the Americans. They were instrumental in helping the United States liberate the Philippines from the Japanese.

Japanese Defenses

Red Beach was narrow but consisted of firm sand. Further inland was flat, marshy ground covered with palm trees and jungle growth. The Japanese had converted a small stream bed in this area into a wide and deep tank trap which paralleled the beach for 1,500 yards. Several large, well-camouflaged pillboxes, connected by tunnels and constructed of palm logs and earth, were scattered throughout the area. Between the swamp and a low range of hills one-and-a-quarter miles inland were open fields and rice paddies. The most prominent terrain feature was Hill 522 which rose directly from the river's edge, north of the small town of Palo. This hill, at a height of 522 feet, commanded the beach area, the town of Palo, and Highway 2, leading into the interior. It was partly wooded, and the Japanese 33d Infantry Regiment had interlaced it with tunnels, trenches, and pillboxes.

Hill 522 presented the most significant terrain feature which would have to be overcome before the American liberation forces could push into the interior from Palo and it constituted one of the chief objectives for ‘A Day’ (20 Oct. 1944). Three months earlier, Japanese General Shiro Makino, who commanded the 16th Division in the Battle of Leyte, had started to fortify it, impressing nearly all of the male population of Palo for the task. By ‘A Day,’ they had constructed five well-camouflaged pillboxes of rocks, planking, and logs, covered with earth. Numerous tunnels honeycombed the hill; the communications trenches were seven feet deep. During the preliminary bombardments of Leyte, the U.S. Navy had delivered some of its heaviest blows to the area, but the bombardment proved to be ineffective in destroying the entrenched Japanese garrison on Hill 522.

U.S. Army X Corp (pronounced as "tenth core") troops delivered by USS Elmore (APA-42) and her sister ships at Palo "Red" Beach on Leyte, 20 October 1944.

Landing at Red Beach

The 24th Infantry Division under Maj. Gen. Frederick A. Irving, was to land on Red Beach on the morning of ‘A Day’ (20 Oct 1944). The 24th Division was to occupy Palo, and secure Highway 1 between Palo and Tanauan. The 19th Infantry on the left (south) was to establish an initial beachhead, advance to the west and south, seize Hill 522, and move on and capture Palo. The 34th Infantry on the right (north) was to establish an initial beachhead, then move westward into the interior and be prepared to assist the 19th Infantry in the capture of Hill 522.

The U.S. Army assaulting forces, having been transferred to landing craft from USS Elmore and her sister ships, met at the line of departure 5,000 yards from shore. After grouping, they dashed for the landing beaches, each regiment in column of battalions. The division landed at 1000 (ten hundred hours or 10:00 am) with regiments abreast according to plan. The Japanese allowed the first five waves to land, but when the other waves were 3,000 to 2,000 yards offshore, they initiated strong artillery and mortar fire against the Americans.

Mortars from the Japanese garrison on Hill 522 had no difficulty in finding their mark on the incoming landing craft. A number of the landing craft carrying the 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry, were hit and four of them sunk. There were numerous casualties: the commanding officer of Company C was killed; a squad of the Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon was almost wiped out; and the Cannon Company suffered the loss of two section leaders, a platoon leader, and part of its headquarters personnel.

Two of USS Elmore’s landing craft were hit by enemy mortar fire, killing Coxswain Franklin Burgess. He was the only battle casualty that Elmore suffered throughout the war. Two U.S. Army soldiers were also killed: Dale H. Hutson and Rosario S. Raniolo. It is uncertain if the two men were in the same LCVP (Higgins boat) as Burgess. The men were buried at sea later that day from the deck of the Elmore.

The destruction continued. Among the vessels hit by Japanese artillery were four LST's, one of which was set on fire. Of the five remaining, two were driven away and three did not get in until much later. The enemy fired upon the retiring LST's, which carried with them the artillery and most of the tanks. The commanding officer of Headquarters Company and the division quartermaster, together with the latter's executive officer, were wounded. Many of the division headquarters personnel were killed or wounded.

The first elements of the 3d Battalion, 34th Infantry, inadvertently landed 300 yards north of the assigned area and were immediately pinned down by heavy machine gun and rifle fire. The commanding officer of the regiment, Col. Aubrey S. Newman, arrived on the beach and, noting the situation, shouted to his men, "Get the hell off the beach. Get up and get moving. Follow me." Thus, urgently prompted, the men followed him into the wooded area.

The Assault on Hill 522

As the day progressed, Army troops of the 19th Infantry Regiment began their assault on Hill 522. The 1st Battalion of the 19th Infantry sent reconnaissance parties to locate a northern route to the hill. The plan had been to move inland from the extreme south of the beachhead, but that area was still in Japanese hands. At 1430, when scouts reported finding a covered route on the northern side of the hill, the 1st Battalion immediately moved out in a column of companies. The column had barely started when Company A, in the lead, was held up by enemy fire from the five pillboxes. The remainder of the battalion moved north around Company A, and, skirting the woods, attacked Hill 522 from the northeast, with Company C on the right and Company B on the left.

The men, although tired from the day's activity and strain, made steady progress up the slope. At dusk Company B reached the first crest of the hill and was halted by fire from two enemy bunkers. The company thereupon dug in.

At the same time scouts from Company C reached the central and highest crest of the hill and observed two platoons of Japanese coming up the other side. They shouted for the remainder of the company to hurry. Company C got to the top of the hill barely ahead of the Japanese, and a sharp engagement took place in which about fifty Japanese were killed. Company C held the highest crest of the hill. During this attack, 1st Lt. Dallas Dick was struck in the leg and his carbine was shot from his hands, but he continued to command his unit until his evacuation forty-eight hours later.

During the night the Japanese made frequent but unsuccessful attempts to infiltrate the company area and, in the darkness, they carried away their dead and wounded. During the action to secure Hill 522, fourteen men of the 1st Battalion were killed and ninety-five wounded; thirty of the latter eventually rejoined their units.

By the evening of 20 October, the Tacloban airfield and Hill 522, overlooking the town of Palo at the northern entrance to Leyte Valley, were in the hands of the X Corps [pronounced as "tenth core"]. Maj. Gen. Frederick A. Irving, who had assumed command of the 24th Division ashore at 1420 hours [2:20 pm], later said that if Hill 522 had not been secured when it was, the Americans might have suffered a thousand casualties in the assault.

Aftermath

The campaign for Leyte proved to be the first and most decisive operation in the American reconquest of the Philippines. Japanese losses in the campaign were heavy, with the army losing four divisions and several separate combat units, while the navy lost 26 major warships and 46 large transports and hundreds of merchant ships. The struggle also reduced Japanese land-based air capability in the Philippines by more than 50%. Some 250,000 troops still remained on Luzon, but the loss of air and naval support at Leyte so narrowed the Japanese options that they now had to fight a passive defensive of Luzon, the largest and most important island in the Philippines. In effect, once the decisive battle of Leyte was lost, the Japanese gave up hope of retaining the Philippines, conceding to the Allies a critical bastion from which Japan could be easily cut off from outside resources, and from which the final assaults on the Japanese home islands could be launched.

Primary Source: U.S. Army in WWII, The War in the Pacific. Leyte: The Return to the Philippines. By M. Hamlin Cannon. Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. Washington, D.C., 1993. Provided online by the HyperWar Foundation.

Additional Source: Wikipedia

Additional Source: Manilla Bulletin newspaper online

Read the Chicago Tribune article about a soldier revisiting Leyte, 25 years later

Return to Leyte (1970)

Where is this place?

See the battlefield in 3-D

The story in photos

Crewmen of the USS Elmore (APA-42) hoisting LCVPs as part of disembarking United States Army troops of the 19th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion for the beaches at Leyte, Philippines, 20 Oct 1944. (Photographer: Robert Sorace, United States Army Signal Corps.)

United States Army soldiers in LCVP [Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel] heading towards a smoke-covered beach during an amphibious invasion. Official caption on front: "Assault troops head for the Leyte beach. US Army Photo 150-2." Leyte, Philippines. 20 Oct 1944.

First wave of American liberation forces storming ashore from amphibious landing craft, Leyte, Philippine Islands, 20 Oct 1944. (United States National Archives)

US infantrymen move cautiously toward a Japanese machine gun nest. (United States National Archives)

1st Cavalry Division crossing a swamp during the Battle of Leyte. (United States National Archives)

Hill 522 today

Webmaster's Note: Both the brief slide show (above) and the YouTube video (below) highlight modern-day Palo in the Philippine providence of Leyte. The focus is on Hill 522 which has become a tourist attraction in the area. The visuals really help to give you a sense of being there and grasping the size and scope of Hill 522 relative to the rest of the town. After seeing these images, I recalled the comments made by Chicago Tribune reporter, Arthur Veysey. He was an army war correspondent in the landing at Red Beach (transported on USS Elmore) and the subsequent fighting in Leyte. He returned to Leyte 25 years later (1970) and, upon seeing Hill 522, incredulously observed that, "It didn't seem nearly as tall or steep as I remembered it." But nobody was shooting at him this time around. Context changes perception.

Today, Hill 522, also called Guinhangdan Hill, is a quiet park. In 2018, the local government of Palo designated Guinhangdan Hill as a tourist attraction. The area around the town of Palo is best known as the site of the historic landing of Gen. Douglas MacArthur at Palo (Red) Beach.

With a height of 522 feet, the hill was the entrance to the first liberated town of Palo in 1944 after having been heavily bombarded to destroy the garrisons built by the Japanese artillery units. Fierce fighting on the hill lasted for two days from October 20 to 21,1944 and claimed the lives of about 50 Japanese soldiers and at least three American soldiers.

A large cross is located at the top of Guinhangdan Hill, which is a favorite pilgrimage site during Holy Week. Thousands of Catholic devotees climb the 522 steps leading to the cross where they offer candles and flowers. The site offers a panoramic view of Palo town, which was one of the places Pope Francis visited in 2015.

Hill 522 YouTube Video Tour

This is a short video tour of Hill 522. There are some great aerial drone shots throughout the video. It is done by a local 12-year-old Filipino boy who has some serious talent. He is speaking in Filipino although the video has English titles interspersed throughout so that you will get the idea. Guinhangdan Hill (Hill 522) is a favorite pilgrimage site during Holy Week where thousands of Roman Catholic devotees in Leyte climb the 522 steps leading to the cross to offer candles and flowers.