Elmore and the 24th Infantry Division at Leyte Gulf

Elements of the 24th Division were transported aboard USS Elmore as part of the invasion of Leyte in October, 1944.

In the first days of October 1944, USS Elmore was anchored at Humboldt Bay off the Northern Coast of New Guinea, in preparation for the upcoming invasion of the Philippines. As this was an Army operation under General Douglas MacArthur, the ship would be transporting army troops to the beaches of Leyte Gulf. From 8 October to 11 October, Elmore loaded combat troops of the First Army Corps, 3rd Battalion, 24th Division. For the next week, the troops practiced amphibious landing operations at nearby Sko Beach, preparing for the upcoming invasion.

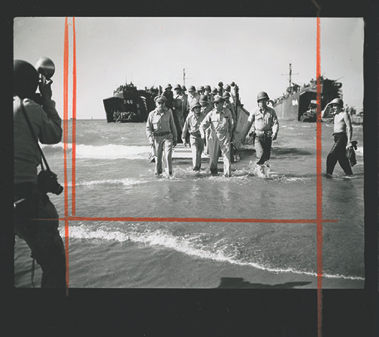

The famous image of General Douglas MacArthur making his return to the Philippines.

The Army's 24th Infantry Division at Leyte

The Army’s 24th Infantry Division was among the first US Army divisions to see combat in World War II and among the last to stop fighting. The division was headquartered at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, when the Japanese launched their attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The 24th suffered casualties during the attack. In May 1943, the 24th Infantry Division staged to New Guinea. Despite resistance from the isolated Japanese forces in the area, the 24th Infantry Division advanced rapidly through the region. In two months, the 24th Division crossed the entirety of New Guinea. After occupation duty in the Hollandia area, the 24th Division was assigned to X Corps of the Sixth Army in preparation for the invasion of the Philippines.

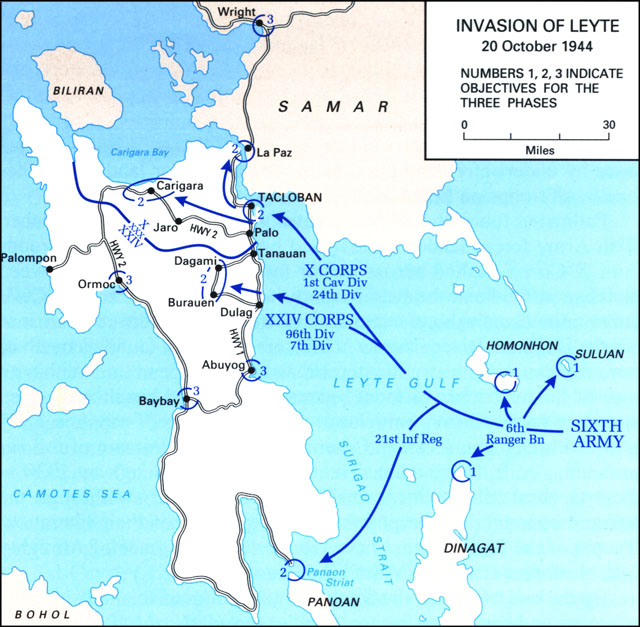

Upon landing on “Red Beach,” the 24th Division’s immediate objective was to seize the town of Palo and advance rapidly to the northwest. The seizure of these areas would secure the important coastal airstrips for future air operations, cut off any Japanese attempts at reinforcement from the southern Philippines, secure the important eastern entrances into the interior, and enable the American forces to control San Pedro Bay and San Juanico Strait.

On 20 October, Elmore arrived in the Transport Area of Leyte Gulf in San Pedro Gulf and began unloading troops and cargo as part of the invasion. During the day, the ship had five seamen injured and one killed from mortar fire on the beach. Enemy aircraft triggered an Air Flash “Red” alert resulting in the ship going to General Quarters. This was the beginning of Japan’s desperate kamikaze scourge.

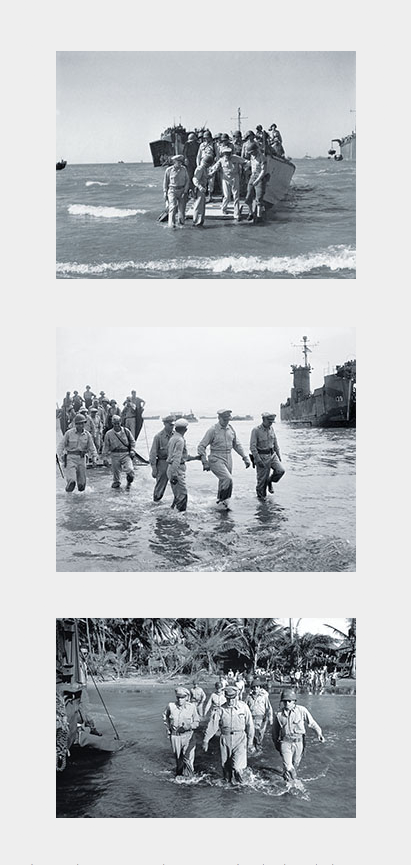

Landing barges loaded with troops sweep toward the beaches of Leyte Island as American and Jap planes duel to the death overhead. Troops watch the drama being written in the skies as they approach the hellfire on the shore on 20 October, 1944.

A number of the landing craft carrying the 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry, were hit and four of them sunk. There were numerous casualties: the commanding officer of Company C was killed; a squad of the Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon was almost wiped out; and the Cannon Company suffered the loss of two section leaders, a platoon leader, and part of its headquarters personnel.

The Japanese had constructed defensive positions in anticipation of an American assault. Several large, well-camouflaged pillboxes, connected by tunnels and constructed of palm logs and earth, were scattered throughout the area. The most prominent terrain feature was Hill 522 just north of Palo. This hill commanded the beach area, the town of Palo, and Highway 2, leading into the interior. It was partly wooded, and the Japanese had interlaced it with tunnels, trenches, and pillboxes.

By the end of the day, the 24th Division had established a firm beachhead near Palo, averaging a mile in depth, and had secured Hill 522 which overlooked Palo. During the action to secure Hill 522, fourteen men of the 1st Battalion were killed and ninety-five wounded. General Frederick A. Irving, in command of the 24th Division, came ashore at 1420. He later said that if Hill 522 had not been secured when it was, the Americans might have suffered a thousand casualties in the assault.

American troops advance towards San Jose on Leyte Island, Philippine Islands. 20 October 1944.

The 24th Division had secured Palo and the hill fortresses that blocked the entrance into northern Leyte Valley. The corps was now in a position to launch a drive into the interior of the valley. In the advance through northern Leyte Valley the 24th Division lost 210 killed, 859 wounded, and 6 missing in action, but it had killed an estimated 2,970 Japanese and taken 13 prisoners.

The island of Leyte was the first objective of the Philippine campaign and was captured by the end of December 1944. This was followed by the attack on Mindoro, and later, Luzon. Battles continued throughout the island of Luzon in the following weeks, with more U.S. troops having landed on the island. Filipino and American resistance fighters also attacked Japanese positions and secured several locations.

The Allies had taken control of all strategically and economically important locations of Luzon by early March,1945. Small groups of the remaining Japanese forces retreated to the mountainous areas in the north and southeast of the island, where they were besieged for months. Pockets of Japanese soldiers held out in the mountains—most ceasing resistance with the unconditional surrender of Japan, but a scattered few holding out for many years afterwards.

The MacArthur Landing Memorial National Park in Red Beach, Palo, marks the 1944 landing by the American liberation forces. It also has a lagoon where a life-size statue of General MacArthur stands. As a side note, MacArthur's true landing took place at Dulag, Leyte, a few miles to the south.

Invasion of Leyte Map

Source: Wikipedia

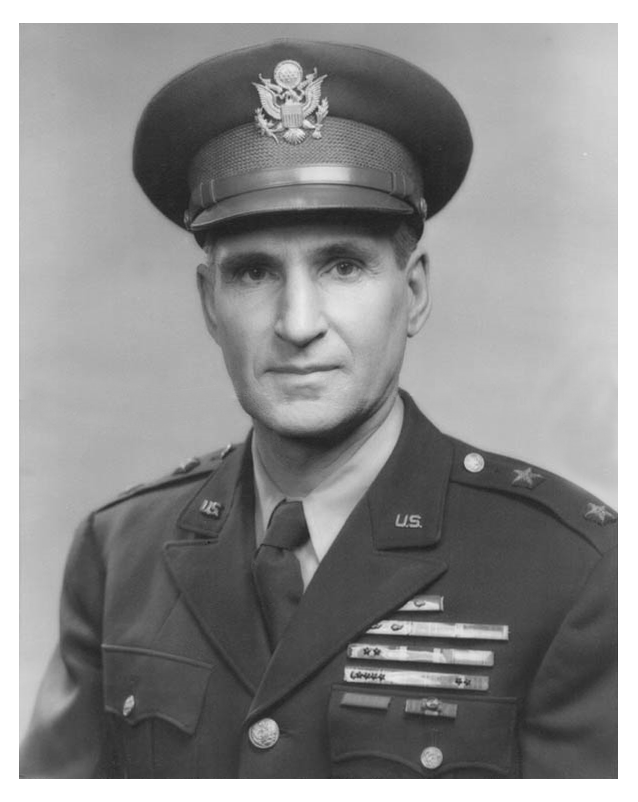

General Fred Irving, US Army

Biography

Major General Frederick Augustus Irving (September 3, 1894 – September 12, 1995) was a United States Army officer who served in both World War I and World War II and was superintendent of the United States Military Academy from 1951–1954.

Irving was a West Point graduate of the class of April 1917, and during the First World War he took part in the St. Mihiel offensive in France. He was wounded during battle and subsequently received the Silver Star for "leading his company through heavy artillery and machine gun fire."

Irving was also active during World War II, leading the 24th Infantry Division during the invasions of Hollandia, New Guinea and Leyte in the Philippines. He was commandant of cadets at West Point from 1941-1942.

Irving's service in the American military extended thirty-seven years, and he retired from service in 1954. He died in 1995 of congestive heart failure at Mount Vernon Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. He was 101.

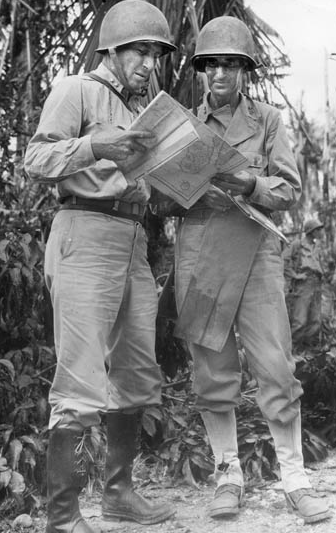

Maj. Gen. Franklin C. Sibert (left), X Corps commander, confers with Maj. Gen. Frederick A. Irving, commander of the 24th Division, at a forward command post, in the invasion of Leyte, Philippines.

"I Have Returned" Speech

In a speech, delivered via radio message from a portable radio set at Leyte, on October 20, 1944 General MacArthur sent this message:

This is the Voice of Freedom,

General MacArthur speaking.

People of the Philippines: I have returned.

By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil – soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come, dedicated and committed to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring, upon a foundation of indestructible strength, the liberties of your people.

At my side is your President, Sergio Osmena, worthy successor of that great patriot, Manuel Quezon, with members of his cabinet. The seat of your government is now, therefore, firmly re-established on Philippine soil.

The hour of your redemption is here. Your patriots have demonstrated an unswerving and resolute devotion to the principles of freedom that challenges the best that is written on the pages of human history.

I now call upon your supreme effort that the enemy may know from the temper of an aroused and outraged people within that he has a force there to contend with no less violent than is the force committed from without.

Rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on. As the lines of battle roll forward to bring you within the zone of operations, rise and strike!

For future generations of your sons and daughters, strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike!

Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of Divine God points the way. Follow in His name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory!

End of the 24th Division

The 24th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army. It was inactivated in October 1996, it was based at Fort Stewart, Georgia and later reactivated at Fort Riley, Kansas. Formed during World War II from the disbanding Hawaiian Division, the division saw action throughout the Pacific theater, first fighting in New Guinea before landing on the Philippine islands of Leyte and Luzon, driving Japanese forces from them.

Following the end of the war, the division participated in occupation duties in Japan, and was the first division to respond at the outbreak of the Korean War. For the first 18 months of the war, the division was heavily engaged on the front lines with North Korean and Chinese forces, suffering over 10,000 casualties. It was withdrawn from the front lines to the reserve force for the remainder of the war after the second battle for Wonju, but returned to Korea for patrol duty at the end of major combat operations.

After its deployment in the Korean War, the division was active in Europe and the United States during the Cold War, but saw relatively little combat until the Persian Gulf War, when it faced the Iraqi military. A few years after that conflict, it was inactivated as part of the post-Cold War U.S. military drawdown of the 1990's. The division was reactivated in October 1999 as a formation for training and deploying U.S. Army National Guard units before its deactivation in October 2006.