The Pacific Strategy, 1941-1944

Prelude

In December 1941 the Imperial Japanese Navy combined ships, aircraft, and doctrine in a unified package that would burst on the global scene in a stunning display of naval airpower. America and the U.S. Navy would have to shake off the shock of that blow, adjust to a new reality, and take the war to the enemy.

At the end of 1941, the aircraft carrier was proven to be the most important capital ship in any fleet. America had eight. Japan led the field with ten ships. Japan also possessed over a thousand front-line aircraft; the United States merely 668. The war in the Pacific would be fought on the sea and in the air, and the Allies were woefully behind in the race.

The Pacific Ocean covers some sixty-four million square miles, more than twice the size of the Atlantic and containing nearly half the earth’s water. The 2,400 statute miles from San Francisco to Honolulu is 50 percent farther than the direct line from Paris to Moscow. The expanse from Hawaii to Tokyo is nearly three times farther still, making the Pacific the largest combat arena in history and war in the Pacific occupying the largest battlefield.

Distances in the Pacific

The oceanic chessboard was defined by squares composed of lines of longitude and latitude. On that strategic surface, aircraft carriers became the leading players—technically marvelous queens with range, mobility, and striking power. In the forty-four months between December 1941 and September 1945, the United States, Britain, and Japan committed immense resources to the naval contest, with the Anglo-Americans dividing their flattops between the Atlantic and Pacific. But the huge majority of carriers of all types were produced in American shipyards. Including escort carriers delivered to Britain, the United States accounted for 71 percent of the world total from 1939 through 1945.

But before the enormous U.S. industrial base could take effect, the sudden war in the Pacific forced its chilling reality upon a marginally prepared fleet.

Unprepared

On December 7, 1941, Japan staged a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, severely damaging the US Pacific Fleet. When Germany and Italy declared war on the United States days later, America found itself in a global war. Japan launched a relentless assault that swept through the US territories of Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, as well as British-controlled Hong Kong, Malaya, and Burma. Yet, with much of the US fleet destroyed and a nation unprepared for war, America and its allies decided they needed to save Great Britain and defeat Germany first.

The Japanese, meanwhile, sought to complete what they began at Pearl Harbor. They aimed to destroy the US carrier fleet in a victory so decisive that the United States would negotiate for peace. With its battleship fleet crippled in Hawaii, the US Navy turned to two surviving assets. Aircraft carriers and submarines mounted a serious challenge to Japan’s triumphant fleet and were critical to protecting mainland America. But as US attacks on Japanese naval forces and merchant ships escalated from isolated raids to full-scale battles, the learning curve proved costly and deadly.

Blunting the Japanese Onslaught

Throughout the winter and spring of 1942 the war news reaching the United States from the Pacific was grim. The Japanese amassed a vast new empire with a defensive perimeter that ranged from western Alaska to the Solomon Islands. In the southwest Pacific, Japan threatened American supply lines to Australia, complicating US plans to use Australia as a staging ground for offensive action.

But within months, the tide of battle started to turn as the United States and its allies in Australia and New Zealand first blunted Japan’s advance and then began a long counterattack across the Pacific. The amphibious invasion soon became the hallmark of the Allied counterattack. As they advanced westward toward Japan, Allied forces repeatedly bombed and stormed Japanese-held territory, targeting tiny islands as well as the jungles of New Guinea and the Philippines. The goal was to dislodge the enemy and to secure airfields and supply bases that could serve as the launching points for future attacks.

USS Arizona burned for two days after being hit by a Japanese bomb in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In early May 1942, US and Japanese carrier forces clashed in the Battle of the Coral Sea. While both sides suffered major losses, the US Navy checked a major Japanese offensive for the first time. Then, in the Battle of Midway the following month, US carrier aircraft dealt a devastating blow to the Japanese navy, destroying four aircraft carriers. The battle marked the first major US victory against Japan and was a turning point in the war.

By shifting the balance of naval power in the Pacific, Midway allowed US forces to take the offensive for the first time. The Allies soon set their sights on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands and on New Guinea.

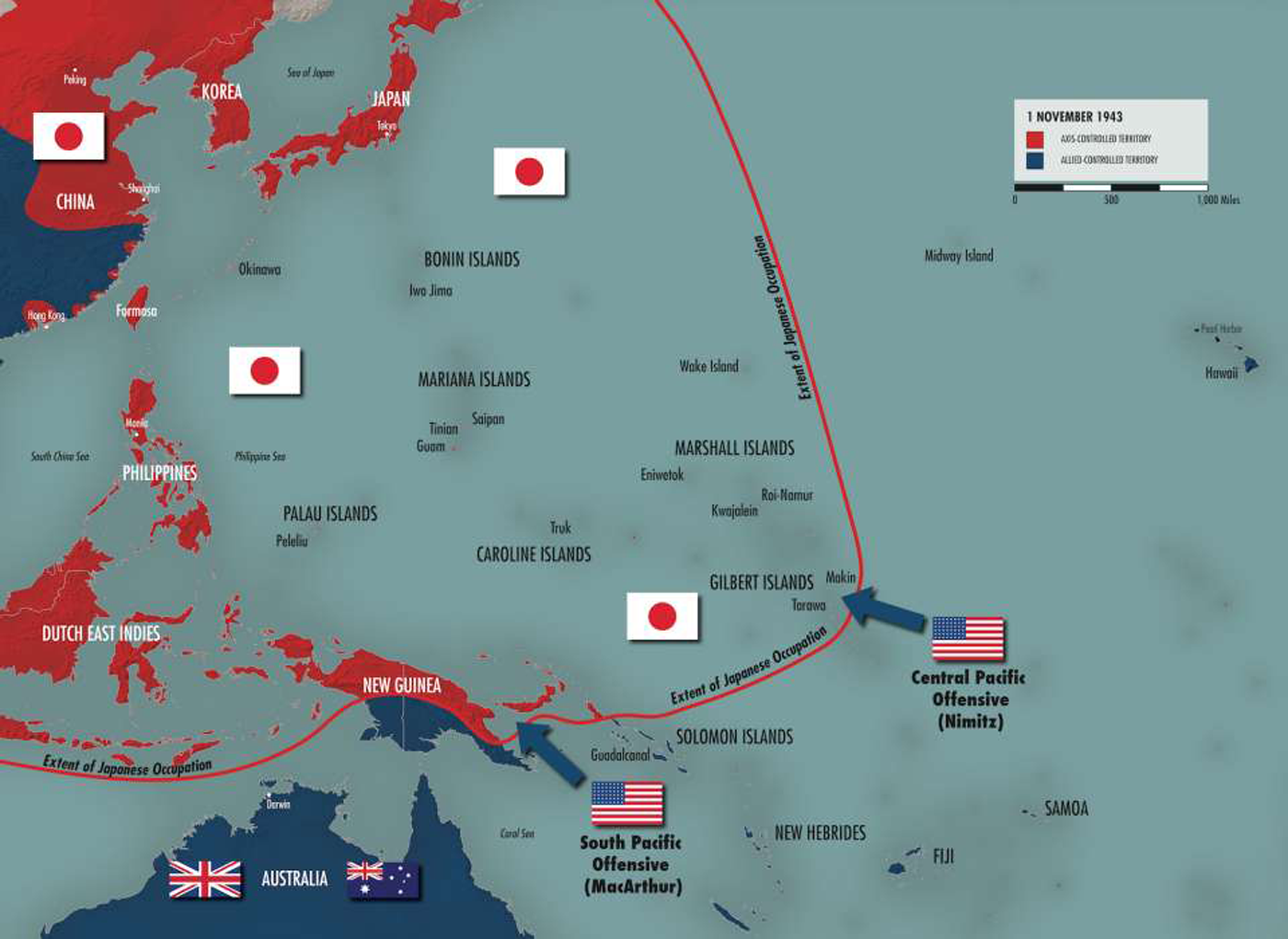

The two-pronged strategy of Nimitz and MacArthur.

Amphibious Invasions

But to win in the vast expanse of the Pacific, the U.S. would need to develop new forms of mobile warfare. They would be based on amphibious landings supported by aircraft flying from carriers.

In August 1942, the United States mounted its first major amphibious landing in World War II at Guadalcanal, using innovative landing craft built by Higgins Industries in New Orleans. By seizing a strategic airfield site on the island, the United States halted Japanese efforts to disrupt supply routes to Australia and New Zealand. The invasion ignited a ferocious struggle marked by seven major naval battles, three major land battles, and almost continuous air combat as both sides sought to control Henderson Field, named after Loy Henderson, an aviator killed at the Battle of Midway. For six long months US forces fought to hold the island. In the end they prevailed, and the Allies took the first vital step in driving the Japanese back in the Pacific theater.

With Guadalcanal in American hands, Allied forces continued to close in on Rabaul in New Britain. As forces under the command of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey moved north through the Solomons, General Douglas MacArthur’s troops pushed west along the northern coast of Papua New Guinea, grinding out a hard-fought victory by March 1943.

By early 1943, the Japanese Empire was at its height. The country had occupied Malaya and Burma, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, Indonesia today. These territories had become vital sources of strategic supplies such as oil and rubber.

Now the United States laid plans to roll back the Japanese gains. The aim was to cut the country’s supply lines by seizing the occupied territories. Japan could then be gradually strangled to death.

But to win in the vast expanse of the Pacific, the U.S. would need to develop new forms of mobile warfare. They would be based on amphibious landings supported by aircraft flying from carriers.

Two Strategic Options

Back in the Spring of 1943, the US military chiefs faced a dilemma. They had been presented with two options for the defeat of Japan. The flamboyant U.S. Army General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the US and Australian forces in the Southwest Pacific, favored a primarily land-based route. His idea was to seize the Solomon Islands, Papua, New Guinea and the Philippines. They could then be turned into a strategic barrier that would cut off Japan from its newly conquered lands in Burma, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Japan would be starved into surrender. Equally importantly, this plan mean that MacArthur could repay a debt. Earlier in the war, he had been kicked out of the Philippines by the Japanese and he had promised to return to liberate the country.

But the US Navy had a different idea. It would bypass the heavily-defended Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines. Instead, it would seize a string of smaller islands scattered across the Central Pacific and close to the Japanese homeland. This strategy was possible in part because the Allies used submarine and air attacks to blockade and isolate Japanese bases, weakening their garrisons and reducing the Japanese ability to resupply and reinforce them. Thus, troops on islands which had been bypassed, such as the major base at Rabaul, were useless to the Japanese war effort and left to "wither on the vine".

Rather than a barrier, the US would have a series of strategic bases from which to attack Japan’s supply lines. They argued that it would be swifter and much more economic. The American military command put off the decision. Both the Army and the Navy were told to go ahead.

Island Hopping

The Navy’s strategy was termed “leapfrogging” or “island hopping”. The idea was to bypass heavily-fortified Japanese positions and instead concentrate the limited Allied resources on strategically important islands that were not well defended but capable of supporting the drive to the main islands of Japan. Leapfrogging would allow the United States forces to reach Japan quickly and not expend the time, manpower, and supplies to capture every Japanese-held island on the way. It would give the Allies the advantage of surprise and keep the Japanese off balance.

Advancing on Two Fronts

In addition to hopping from one less-defended island to another, the Allies’ Pacific strategy developed another key feature: soldiers, sailors, and US Marines pressed forward on two fronts. As MacArthur’s troops leapt from island to island in the southwest Pacific, a central Pacific campaign began with the invasion of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands in November 1943. By the end of the year, a two-pronged assault on Japan was well underway.

As 1944 began, the southwest Pacific was largely under Allied control. By February, the Allies were also making progress in the central Pacific. Naval and air strikes reduced most of the Japanese bases throughout the area, and after several intense, bloody campaigns, most of the central Pacific was secure. As the islands in the Marshall and Mariana chains fell to US Army and Marines forces by that summer, troops constructed airfields in preparation for air strikes on Japan itself. The Marianas were a particularly valuable asset since they were close enough to Japan for the United States’ new, technologically advanced B-29 bombers to reach the Japanese mainland.

The American military strategy turned the vast Pacific distances into an American ally, and the United States used it to leapfrog across the Pacific towards Japan. The only question that remained for military planners was the determination of the Japanese leaders to resist. Could the isolation of Japan, starvation and deprivation, force a surrender or would a full-scale military invasion be required?

Sources: Wikipedia and The National World War II Museum