10 Facts About the Kamikaze You Probably Didn’t Know

Kamikaze suicide attacks were one of the most frightful tactics of the Pacific theater during World War II. Named after the divine wind of a hurricane that repelled Mongol invaders in Japan’s ancient past, these planes and pilots are often thought of as nothing more than fanatics, brainwashed into giving their lives, but the truth is more nuanced. These pilots were as human as any and often battled between loyalty and their fear of death. The details of the Kamikaze attacks are a history lesson that we should not forget.

10

The First Kamikaze Attack Was Not Planned

During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec 7, 1941, 28-year-old Lieutenant Fusata Iida was hit. His plane, a Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero, had sustained heavy damage, and he signaled the rest of his air group to go on without him. He pointed to the ground, indicating his intention to crash his plane at a suitable target. He targeted Hanger 101, the base’s primary hanger, which he intended to ram in a suicide run. American ground fire ripped his plane apart and instead of hitting the hanger his plane overshot and crashed.

Fusata Iida is widely considered the first Kamikaze, though that was not his intention setting out. His body was buried by Americans at the Heleloa burial area, and a memorial now marks the site of his crash. His remains have since been returned to Japan.

9

The First Planned Kamikazes Weren’t Until Three Years Later

Conventional naval and aerial tactics failed to stop the American offensive after Pearl Harbor. This desperate situation led to a new tactic. Japanese naval Captain Motoharu Okamura said of the matter, “I firmly believe that the only way to swing the war in our favor is to resort to crash-dive attacks with our planes . . . There will be more than enough volunteers for this chance to save our country.”

The first wave of Kamikazes were made up of 24 volunteer pilots from Japan’s 201st Air Group. They specifically target US escort carriers. The St. Lo was one such carrier that was struck and sunk in less than one hour, killing 100 Americans.

8

Battle of Okinawa’s Heavy Loses

The Battle of Okinawa was an intense 82-day campaign involving more than 287,000 US and 130,000 Japanese troops. It was considered the bloodiest battle of the Pacific Theater, and more than 90,000 men died from both sides, along with almost 100,000 civilian casualties. During this conflict, Kamikazes inflicted the greatest damage ever sustained by the US Navy in a single battle, killing almost 5,000 men.

All told, Kamikazes sank 34 ships and damaged hundreds of others during the entire war.

7

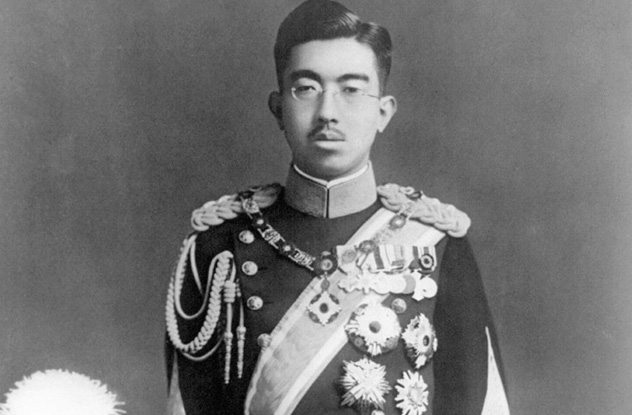

The Emperor Personally Visited Them

Hisao Horiyama is one of the few surviving Kamikaze pilots. At the time, he was a 21-year-old airmen caught in a faltering war. Horiyama has said, “We didn’t think too much about dying. We were trained to suppress our emotions. Even if we were to die, we knew it was for a worthy cause. Dying was the ultimate fulfillment of our duty, and we were commanded not to return. We knew that if we returned alive that our superiors would be angry.

“When we graduated from army training school, the Showa emperor visited our unit on a white horse. I thought then that this was a sign that he was personally requesting our services. I knew that I had no choice but to die for him.”

As for why his duty insisted he volunteer, he added, “At that time, we believed that the emperor and nation of Japan were one and the same.” Ultimately, the war was over before Horiyama was sent into battle as a Kamikaze pilot.

6

Pilots Wrote Their Family Final Letters

Like all Kamikaze pilots, Horiyama was asked to pen a letter and will, which were to be sent to his family after his death. He said, “I was a disrespectful child and got poor grades at school. I told my father that I was sorry for being such a bad student, and for crashing three planes during training exercises. And I was sorry that the course of the war seemed to be turning against Japan. I wanted to prove myself to him, and that’s why I volunteered to join the special attack unit.

“But my mother was upset. Just before she died, she told me that she would never have forgiven my father if I had died in a kamikaze attack. So I’m grateful to the emperor that he stopped the war.”

Another such letter, written by 23-year-old Adachi Takuya to his parents before his death as a Kamikaze pilot on April 28, 1945, has been preserved in its entirety:

Honorable Mother and Father,

The difficulty of the journey you made to see me was clearly evident in your disheveled hair and in the hollows under your eyes-it made me want to bend my knees and worship before you. In the wrinkles on your brows was vivid testimony of the pains you took to raise me. Words could not express my feelings, and what little I did say was superficial in the extreme.

Yet, although acutely conscious of how little time we had, I saw in your eyes and in your gaze all you wanted to say but couldn’t.

When you took my hand and passed it over your chilblains, I experienced a sense of profound peacefulness unlike anything I have experienced since joining up -like being a baby again and longing for the warmth of a mother’s love. It is because I bask in the beauty of your deep devotion that I can martyr myself for you-for in death I will sleep in the world of your love. Washed down with my tears was the sushi you prepared with such loving care, for it was like putting your love to my lips. Though I ate but little, it was the most delicious meal of my life.

Honorable Mother, even if I was never able to fully accept the love you gave me, I received so much wisdom from you. And Father, your silent words are carved deeply into my heart. With this I will be able to fight together with you both. Even if I should die, it will be with a peaceful spirit. I mean this with all my heart.

The war zone is where these beautiful emotions are put to the test. If death means a return to this world of love, there is no need for me to fear. There is nothing left to do but press on and fulfill my duty.

At 1600 hours our meeting was over. Watching you walk out the gate, I quietly waved goodbye.

5

Not All Kamikaze Pilots Were Willing

Horiyama was disappointed he survived, feeling he failed in his duties. He said, “I felt bad that I hadn’t been able to sacrifice myself for my country. My comrades who had died would be remembered in infinite glory, but I had missed my chance to die in the same way. I felt like I had let everyone down.” But not all of his fellows felt the same.

Takehiko Ena, another surviving Kamikaze pilot, relates that when he received his assignment as a Kamikaze, “I felt the blood drain from my face. The other pilots and I congratulated each other when the order came through that we were going to attack. It sounds strange now, as there was nothing to celebrate. On the surface, we were doing it for our country. We made ourselves believe that we had been chosen to make this sacrifice. I just wanted to protect the father and mother I loved. And we were all scared.”

4

Kamikazes Were Often Mechanically Unsound

Takehiko Ena, who is now in his nineties, survived World War II only because of ongoing technical problems with the aging planes forced into service toward the end of the war. Many such planes had been stripped and adapted into Kamikazes. Ena’s first attempt at flying a Kamikaze ended before the plane could get airborne. His second mission also ended without success when his plane’s engine suffered from mechanical problems and forced him to make an emergency landing, still carrying the bomb meant to kill himself and the enemy.

In his third and final attempt, engine trouble forced another emergency landing, this time into the sea. Ena and two others with him survived by swimming to a nearby island and were rescued some two months later by a Japanese submarine. Soon thereafter, the war was over. Ena’s salvation came from the poor condition of the Kamikaze fleet.

3

Kamikaze Pilots Were Used As Propaganda

One famous case of this was with Arima Masafumi, who served as the commander of the 26th Air Flotilla. He was described as a personable commanding officer who took the time to greet his crew every day with a “good morning” and as the “picture of dignity,” even wearing his full uniform in the topical heat.

Masafumi personally participated in a suicide attack against the US fleet off the Philippine Islands. He specifically targeted carrier Franklin but was reportedly shot down before he was able to crash into her. Despite this, a report was made from Tokyo that he had succeeded in crippling the ship and in so doing, “lit the fuse of the ardent wishes of his men.” He was posthumously promoted to the rank of vice admiral.

2

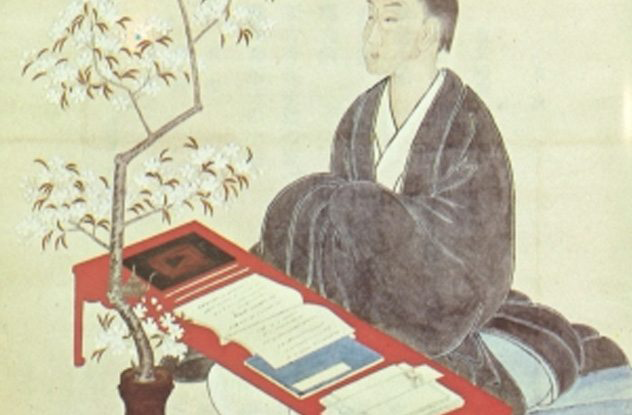

Kamikaze Units Were Named from a Poem

“Tanka” is Japanese for “short poem.” One of the most famous was written by the scholar Motoori Norinaga in the Edo era. It reads:

Shikishima no

yamato-gokoro o

hito towaba

asahi ni niou

yamazakura-bana

If someone inquires

about the Japanese soul

of these Blessed Isles,

say mountain cherry blossoms,

fragrant in the morning sun.

Shikishima (Islands of Japan), Yamato (A traditional name for Japan), Asahi (rising sun), and Yamazakura (mountain cherry) were the names of the first four Kamikaze units.

1

Kamikaze Pilots Were Given a Manual

They kept these manuals in their cockpit, which contained both a guide on how to handle their mission and a series of inspiring thoughts and reassurance. One paragraph explains what to do in the event of an aborted mission: “In the event of poor weather conditions when you cannot locate the target, or under other adverse circumstances, you may decide to return to base. Don’t be discouraged. Do not waste your life lightly. You should not be possessed by petty emotions. Think how you can best defend the motherland. Remember what the wing commander has told you. You should return to the base jovially and without remorse.

”The Manual also explained a Kamikaze pilot’s mission: “Transcend life and death. When you eliminate all thoughts about life and death, you will be able to totally disregard your earthly life. This will also enable you to concentrate your attention on eradicating the enemy with unwavering determination, meanwhile reinforcing your excellence in flight skills.”

And it also contained this short message: “Be always pure-hearted and cheerful. A loyal fighting man is a pure-hearted and filial son.”

Source: listverse.com - A. C. Lu - February 5, 2017