The USS DuPage: Braving Kamikazes From Air And Sea

By Don Smart

Warfare History Network

August 21, 2015

The crew of the attack transport DuPage braved kamikaze attacks while supporting American landings in the Philippines.

The mighty invasion armada for the main thrust at Luzon in the Philippine Islands was being assembled on December 28, 1944. The troops came from widely dispersed staging areas—Bougainville, New Britain, Hollandia, Aitape, Sansapor, and the farthest away, New Caledonia. Loading elements of the 43rd Infantry Division at Aitape, New Guinea, were the attack transport USS DuPage (APA 41) and her sister ships [including USS Elmore (APA-42)]. For the DuPage this invasion would produce a traumatic event that the ship’s crew had witnessed but never experienced.

A Multi-Purpose Vessel

The basic design for the DuPage was a five-hatch cargo ship powered by an 8,500-horsepower steam turbine that could move it up to a speed of 16.5 knots. This hull configuration was used for escort carriers and troop transports (AP) in addition to attack transports (APA). The APA had many purposes, but the main one was to load troops and equipment, transport them to an invasion area, and put them ashore.

A memorable description of the attack transport was given by author Sidney Carrol in a 1940’s edition of Coronet Magazine. “An APA is a tenement, a moving van, a freight car, a garage, a fighting ship, a hospital, an ambulance and a hearse.” In a few short days the DuPage would learn that one more item could be added to the list: target of the divine wind, better known as the kamikaze.

Rough Start To The Pacific War For Americans

For America, the early months of the war in the Pacific meant one defeat after another. This was climaxed in May 1942 with the fall of the Philippine Islands. For the thousands of soldiers who went into captivity at this time, their only hope was a statement from General Douglas MacArthur: “I shall return.” By late 1942 the Allied armies had started forward. The forces of General MacArthur had driven up the north coast of New Guinea all the way to Morotai Island, lying just south of the Philippines. At the same time, the forces of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz had started a drive through the islands to the east that included the Solomons, Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas. By mid-1944 the Allied forces were ready to take the next step toward the Home Islands of Japan.

MacArthur developed a three-phase plan for recapture of the Philippines: First, seize the island of Leyte to be used as a marshaling area and supply base; second, invade and clear the Japanese from the main island of Luzon; and third, occupy the bypassed islands at a later date. The main invasion of Luzon would proceed via the Lingayen Gulf. This area had excellent beaches, plus access to the island’s central plain and a direct road to the Manila Bay region.

Forty-Mile Convoy Forms A Protective Shield For The Invasion

The Allies had to invade and secure the small island of Mindoro before the main invasion could go forward, because two airfields there could support Japanese attacks on the invasion fleet. Mindoro was taken by mid-December and the airfields converted for Army Air Force use. With the sea lanes protected, the Luzon invasion moved forward. The overall force commander was Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid. In command of the fire support groups was Vice Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, and Vice Adm. Daniel E. Barby was over the transport groups.

The first elements of the attack force, Task Group 77.6, consisting of minesweeping and hydrographic units, departed on January 2, 1945. This force was followed by Task Group 77.2, the bombardment and fire support vessels accompanied by 12 escort carriers and their screening destroyers and destroyer escorts. By January 5 the entire 7th Amphibious Force carrying I Army Corps, followed by the 3rd Amphibious Force carrying XIV Army Corps, was moving out of Leyte Gulf into Surigao Strait. This armada of transports and their protective shield formed a convoy over 40 miles long.

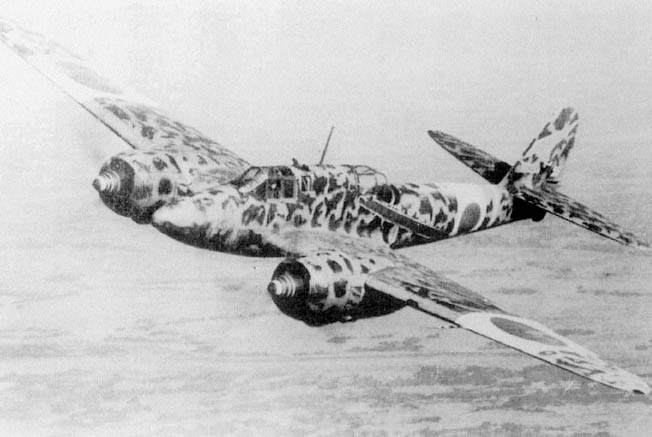

Kamikazes Set Sights On Convoy

The kamikazes—Japanese suicide planes piloted by fliers bent on sacrificing themselves by diving their aircraft into American naval vessels—soon found the strung-out convoy. The leading elements of the task force were bombed, and six kamikazes jumped the force, damaging an oiler and minesweeper. As the main force moved ahead, the attacks continued. A heavy cruiser was damaged, and an escort carrier was sunk. The American commanders were in a quandary as to where the attacks were originating. MacArthur believed the planes were from air bases on Luzon, while Oldendorf assumed they had come from Formosa. To support the convoy, Admiral William F. Halsey committed the aircraft of his Third Fleet against installations on Luzon as far south as Clark Field.

By January 5, as Halsey’s fast carriers were in position to strike Luzon, Oldendorf’s forward groups were having a rough time. Two escort carriers, two heavy cruisers, two destroyers, a destroyer escort, and several other ships were damaged by kamikaze attacks. The invasion force reached Lingayen Gulf on January 6 and commenced sweeping operations and fire support. The kamikazes kept coming. A minesweeper was sunk; two battleships, two heavy cruisers, and other smaller vessels were damaged. The Japanese had killed 300 American sailors, wounded 760, and sunk two ships, but they could not stop the operation.

Transports Ferried Invasion Troops To Philippines

The DuPage was steaming as flagship for her division in Task Unit 78.1.2 along with 15 other APAs and APs. At Aitape Roads, New Guinea, the DuPage had embarked the 1st Battalion, 172nd Regiment, 43rd Division, a total of 79 officers, 997 enlisted men, and 416 tons of equipment.

Captain G.M. Wauchape was in command of the DuPage with Lt. Cmdr. W.P. Toran as executive officer. The fast attack transports carried a crew of 50 officers and 600 seamen. The landing craft complement for the ship included two 50-foot LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized) on the aft deck with a 36-foot LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel) nested in each LCM. Also, the aft deck contained two racks on each side of the ship with 16 LCVPs. On the forward deck, three racks contained eight more LCVPs. The invasion troops were quartered amidships on lower decks 1 and 2. Forward, the heavy equipment, trucks, jeeps, and howitzers were on lower decks 3 and 4.

The trip lasted 11 days and proceeded through the Surigao Strait, Mindanao Sea, Sulu Sea, Mindoro Strait, South China Sea, and into Lingayen Gulf. On the DuPage the crew continuously heard the general quarters’ call and rushed to man battle stations as enemy aircraft were sighted. Seaman 1st Class Rudolph Daniel Wells’ battle station was a 40mm antiaircraft gun.

A Rather Impressive Set Of Guns

“My station was on the rear starboard side,” Wells said. “The quad-40 had a crew of four, two loaders, gunner and trainer. The gunner ran the elevation transverse and trigger, the trainer ran the azimuth transverse.”

The attack transport had a formidable array of antiaircraft weapons. In addition to the quad-40 stations, there were 20mm gun tubs, dual 50-caliber machine guns, and a 5-inch cannon. The defensive configuration of the guns was situated on both the bow and stern of the ship.

Far to the rear, the amphibious assault forces were having problems with Japanese aircraft and submarines. Several torpedoes were fired at the convoy to no effect. As the transports got closer to Lingayen Gulf, they began to come under intense air attack.

New And More Deadly Group Of Suicide Pilots

The DuPage deck log stated, “Enemy aircraft appeared many times; several were shot from the air, one managed to crash into a transport and the rest were repulsed.”

Admiral Oldendorf and the other commanders were worried, with good cause. Previous kamikaze attacks were executed by relatively untrained pilots. Although dangerous, they did not take precautions to avoid detection and antiaircraft fire. The new attacks were different in that the pilots were more skilled, the aircraft larger and more heavily armored. They approached low, out of the evening sun, and would execute radical maneuvers to confuse the ships’ defenders.

On January 9, S-day, the transport division continued to steam into Lingayen Gulf during the early morning hours. The DuPage, with her contingent of transports carrying the troops of the 43rd Division, anchored in the transport area by 7 am. They were 12,000 yards offshore opposite the small town of San Fabian. At 7:15 word came down from division command: “Lower all boats.” The crew immediately commenced lowering all landing craft, and this was completed by 7:49 am.

Critical Landing Craft Timing

The first boat lowered and the last to be retrieved was the LCC (Landing Craft, Command). This boat was manned by a crew of five and coordinated all movements of the LCVPs. The LCVPs were stored in racks on the fore and after decks of the attack transport. Each rack had two davits to attach and lower the boats to the water. This unloading process was accomplished in 30 minutes. In the middle of troop loading, a Japanese fighter plane appeared, and the ship opened fire with all guns to drive it away.

Wells was a crewman on one of the LCVPs. He described the activity getting ready to head for the beach. “Once we got loaded with troops the assault LCVPs would move away from the ship and form up in a large circle. We had to wait until all landing craft from the transports were ready to head in as a part of an assault wave. Once the order came down to the Command Boat that all LCVPs were loaded and ready, we got the order to head for the beach. We came out of the circle, line abreast going in. It was important that all LCVPs hit the beach at the same time.”

The last boats with assault troops were away by 8:12 am.

The first assault wave hit Beach White 1 by 9:35 am, and all assault waves were on the beach by 10. The LCVP had a crew of three. The coxswain was the pilot while the other crewmen manned the two .30-caliber machine guns. As they hit the beach, one crewman would trip the ramp at the front of the LCVP to let the troops off. The second crewman manned the winch to crank up the ramp as they pulled off the beach. Wells’ boat was coming in as part of the third assault wave, and was interspersed with a group of LSTs (Landing Ship Tank).

Dropping Off The Troops, Taking Back the Dead

“I told the Coxswain he should wait until the LSTs got through because the Japanese loved to fire mortars at them,” Wells remembered. “An army lieutenant kept hollering to get them to the beach. We were right in between two LSTs when a mortar shell exploded right in front of the boat. We were lifted about five feet out of the water and slammed back down. No damage except my buddy manning the ramp lever swallowed his chew of tobacco.”

When the DuPage crew got all the assault troops ashore, the laborious process of unloading cargo from the ship holds got under way. This included the battalions’ vehicles stored in holds 2 and 4. These large items were transferred via ship booms to an LSM (Landing Ship, Medium) anchored alongside. This process was delayed by another LSM that brought wounded and dead from the beachhead.

At 2:30 pm, the DuPage moved into the inner transport area to take on casualties and complete equipment unloading. The first load of casualties consisted of three dead and 10 wounded. Later, three more dead and 40 wounded were taken from an LSM. The ship rushed one officer and 25 seamen ashore as a beach working party to assist in unloading the incoming boats. All troop cargo was transferred to the beachhead by 5 pm. The beach party returned to the ship, and the DuPage commenced to rehoist all boats.

Throughout the invasion operations, the ship was undergoing continuous alerts. “FLASH RED-CONTROL GREEN” or “FLASH RED-CONTROL YELLOW” kept the crew hopping to man the antiaircraft batteries. The guns would open fire with a cacophony of noise as the enemy planes approached. All Japanese aircraft were driven away from the invasion armada during S-day.

Suicide Boats And Swimmers Also Posed A Threat

At 6:30 pm, the DuPage weighed anchor and moved to the outer transport area. The DuPage crew now mustered to perform a sad but necessary service, burying the dead at sea. The chaplain conducted the service in which five U.S. Army and two U.S. Navy casualties were buried.

During the invasion, reports of suicide attacks other than those by kamikazes began to come in. “We were ordered to shoot up all floating boxes and trash with the .30-calibers as we went to and from the beach,” recalled Wells. “There had been reports of Japanese swimmers trying to reach the ships under the boxes. They had explosives strapped around their waists to detonate against the side of the ship.”

As night settled over the anchored transports, the Japanese resorted to still another suicide method. This threat was the suicide boat, or Shinyo. In the area with the DuPage, the transport USS War Hawk was riding at anchor. In the early hours of January 10, lookouts reported hearing the sound of a boat approaching. In the dark nothing could be seen, and the Shinyo rammed the port side of the ship. The explosion killed 61 men and tore a 25-foot hole in the hull. The resulting flooding knocked out the engine, leaving the ship dead in the water. The crew fought all through the next day to keep her afloat and restore power.

DuPage Keeps Busy While Troops Move Inland

The War Hawk was repaired enough to make the trip back to Leyte Gulf. Two landing craft, LCI(G)-365 and LCI(M)-974, were sunk on January 10 by suicide boats.

January 10 found the infantry units up to eight miles inland, moving forward against very little resistance. The 172nd Infantry Regiment, landing on the extreme left beach, White 1, had the most hazardous and difficult task. A line of low, grass-covered hills gave the Japanese good defensive positions, with two more low ridges behind the first. These problems notwithstanding, the 43rd Division moved out and expanded its beachhead by two miles.

The DuPage was anchored in the outer transport area going through cleanup routines in preparation for getting underway later in the day. The crew had refueled a destroyer, transferred provisions to an LCI, and continued to care for wounded in its infirmary. Enemy aircraft continued to be a threat, requiring continuous general quarters calls.

“The Bomber Was So Low He Was Pulling Water With His Props”

At 6 pm, the DuPage got underway in accordance with standard procedures for forming up the transport convoy. The DuPage was in formation as guide ship for the convoy of 17 transports and some smaller vessels. Set at thousand-yard intervals, on her left was the USS Fayette, on the right the USS Cavalier, and trailing, the USS Wayne. The destroyers Sumpter, Gascoyne and Pfeiffer were out in front providing protection for the convoy. At 7:02 pm, general quarters was sounded as two Japanese twin-engine bombers were sighted.

“I had just gotten cleaned up when general quarters sounded,” said Wells. “I got my pants and a skivvy shirt on and ran for the gun. My buddy, Waldript, was on the bridge and saw the Jap come in. He said, ‘The bomber was so low he was pulling water with his props.’”

From the deck log of the DuPage, the following notation was entered: “1800—Underway in accordance with ComTransRon 14 visual dispatch. Captain at the conn. 1841—secured from general quarters, set condition III. 1845—change course to 340T, 6 knots, 30 rpm. 1902—sounded general quarters, enemy planes in the vicinity. 1915—twin engine bomber sighted, heading dead on for the USS DuPage, screening destroyer escort USS Cavalier and USS Fayette opened fire on plane.”

A Kamikaze Finds Its Mark

The intense antiaircraft fire caused one aircraft to veer off. The second plane dived to just above the ocean surface, causing the ship’s lookouts to lose sight of it until it was almost on the DuPage, dead ahead at 200 yards. The forward 20mm gun tubs, 2, 4 and 10, commenced firing.

Storekeeper 2nd Class Oliver E. Moreau was stationed on the flying bridge to assist the fire-control officer. His duty was to relay messages to the various gun stations as to targets and position. The aircraft banked slightly left, then turned back to the right, causing the forward gun crews to think the bomber was going to pull up and go over the ship. Moreau remembered the moment the DuPage and the kamikaze came together. He recalled:

“We saw it dive until it was skimming just above the ocean surface. The left wing first hit the barrel of the 20mm gun on the port side and spun the turret and gunner around at a tremendous rate. He was killed instantly. The wing then hit the boom cable, and the plane twisted to hit the port side of the navigation bridge just below us. I heard one 500-pound bomb go off as the plane careened down the ship’s side.”

At 7:15 pm, the left wing of the plane hung on one of the ship’s antimine Paravene boom cables and swung into the left side of the navigation bridge. The plane cartwheeled down the port side of the ship, exploding bombs and fuel.

Live Bomb On Deck With Fire All Around

Lieutenant George R. Cannon was the deck officer in charge of damage-control parties. During general quarters there were three damage control parties, the forward, amidships, and aft units. When the kamikaze hit, Cannon was in his office and in contact with the damage control sections via interphone. Several members of the amidships unit were killed or wounded during the ensuing collision. Cannon headed for the main deck to take charge of the firefighting.

“From the bridge to the aft end of the ship was a mass of flames,” Cannon said. “We had heard one bomb go off and had no idea what else the plane might have had. My forward unit got the fires on the bridge under control and as we started aft, a seaman rushed up and said we had a live bomb on deck, fire all around it.”

Cannon rushed his forward unit to the area and saw a 500-pound bomb in the midst of a sea of flames. He grabbed two men, and with the fire hoses soaking them down, started to get the bomb untangled from cables and beams.

Tossed Over the Side Just In Time

“The bomb was still very hot from the fire plus the three of us could not lift it over the ship’s rail,” Cannon continued. “I motioned to two more men and we manhandled the bomb over the side. About that time, I thought, ‘I’m going to be some damage control officer if this thing goes off when it hits the water.’ All this time the loudspeaker kept up a constant, ‘Lt. Cannon report to the bridge.’ I was a little too busy to stop right then.”

When Cannon made it to the bridge, the captain informed him there was a bomb on the deck and that it needed to be removed. Cannon was able to report the job already done. Seaman lst Class Vernon L. Neilson was a member of the Quartermaster section, stationed in the after steering control room. It was located in the ship’s stern just over the shaft alley. In case the steering controls on the bridge were disabled, the ship could be controlled from this area. Neilson had just stepped up to the deck above the control room and was standing behind the 5-inch gun, leaning on the bulkhead just below the Quad 40mm gun tubs, when the Japanese suicide plane hit the DuPage.

Kamikaze Calls Strike Two Against DuPage

“I saw the ships on either side of the DuPage shooting with their guns aimed just above the water,” remembered Neilson. “I had no idea what they were shooting at, then the kamikaze hit. Fire came rolling down the port side and over the top of me. My life jacket immediately caught fire, but I got it put out.”

Death and destruction followed the big bomber down the side of the ship. In addition to killing members of the amidships damage control party, the crash killed all five crew members of the command boat aboard their craft.

“I heard the boy in the crow’s nest yelling in the interphone,” commented Wells. “I got up from my seat to see what he was hollering about. The aft section crew couldn’t see anything. Suddenly I was lifted off my feet and slammed into the bulkhead, knocking me out. When I came to seconds later, a sailor was kicking fire off me. Never did know who he was. I had a wound in my leg, and my right arm was burned.”

Death And Horror Onboard

Wells and his gun crew immediately started throwing the 5-inch ammunition overboard. Neilson could not remember what happened to the 5-inch gun crew, but saw the gun lift up and off its stand when the plane hit. He rushed to throw a shell and powder casing over the side. Then he saw the first wounded.

“A sailor stumbled out of the inferno and collapsed in my arms,” he recalled. “He was wounded and burned bad, real bad. I grabbed him and helped him to the rail. I planned to get both of us over the side in case the ship was sinking. Just then we got hit by water from the fire hose and pushed back against the bulkhead. The guy died in my arms before a corpsman arrived.”

The captain reported the suicide crash to the USS Cavalier and advised that the DuPage could maintain position as guide in cruising formation. The ship then sent out a voice radio message requesting all ships astern to be on the lookout for men blown overboard. The USS Wayne was steaming a thousand yards astern, and her crew members saw the kamikaze strike and several men go over the side. The Wayne crew scrambled to throw life preservers to the swimming sailors as the ship steamed by, since the transports in the convoy could not stop. By 7:37 pm damage control parties reported all fires extinguished and under control.

Assessing the Damage

The captain then started to assess the damage and determine casualties. The port wing of the navigation bridge was demolished, numbers 2 and 4 davits were demolished, and all LCVPs cradled in these davits wrecked. Gun tubs 16 and 18 were wrecked, decks along the port side were holed and bulkheads badly warped. All the wounded were ordered to the infirmary, and a crew count commenced. Wells and the gun crews in the aft section helped contain the fires and throw all explosive material overboard. When the ship was declared secure, they looked around their area for casualties.

“When we looked at the 20mm gun port on the deck above us, the boy in the gunner’s seat was dead,” said Wells. “A large chunk of the airplane had sliced through the area and took his head off. When I looked at my gun station, the seat I was sitting in was also blown off. I heaved a sigh of relief.”

The captain found 32 men killed outright with 160 sustaining various levels of wounds. Three of the wounded died the following day. There were also five men listed as missing and assumed blown over the side. Neilson remembered one of the five was a black sailor from the officers’ mess, who later stated, “I couldn’t swim at the time, however, I learned real fast.” At 11:30 pm, a message from the destroyer USS O’Brien came in reporting that five survivors from the DuPage had been picked up. As the hours of January 10 waned, the captain put out a call for medical assistance for his vessel.

Immense Losses On Both Sides

The next morning two boatloads of medical officers and pharmacists came aboard from the USS Wayne and USS Fuller. At 4 pm on January 11, the DuPage pulled out of station to the left of the column, assigning guide duties to the USS Cavalier. The ship’s chaplain officiated the service to bury the DuPage’s dead at sea.

January 13 brought the last significant kamikaze attacks on the Luzon attack force. For the Allied naval forces, a welcome respite followed. From December 13, 1944, to January 13, 1945, the Japanese succeeded in sinking 24 vessels and damaging 67 others in action off the Philippines. In accomplishing this, the Japanese lost 600 aircraft, with at least one-third of this number being kamikazes. With these losses, Japanese air power ceased to exist in the Philippines. Australian and U.S. naval forces suffered 1,230 men killed and 1,800 wounded by the kamikazes during the Philippine operation. The kamikazes were not through, however, as demonstrated in April during the Okinawa invasion. In that bloody struggle, damage to U.S. Navy vessels would far surpass that sustained at Luzon.

Transporting The Troops Home

The DuPage continued on with the convoy to Leyte Gulf, where she anchored on January 13. The wounded were transferred to hospital ships USS Mercy and USS Marigold. Emergency repairs were made from January 13-20, and the DuPage prepared to return to war. The DuPage continued her service of moving troops and supplies and supporting invasions until the end of the war. Her last orders assigned her to Operation Magic Carpet, transporting American veterans home.

The service of the USS DuPage was continuous and honorable throughout the war, but one particular incident stands out. Her crew will always remember January 10, 1945, as the day of the kamikaze.

Source: warfarehistorynetwork.com