The Pacific Fleet

Overview

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a Pacific Ocean theater-level component command of the United States Navy that provides naval forces to the United States Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Pearl Harbor Naval Station, Hawaii, with large secondary facilities at North Island, San Diego Bay on the Mainland.

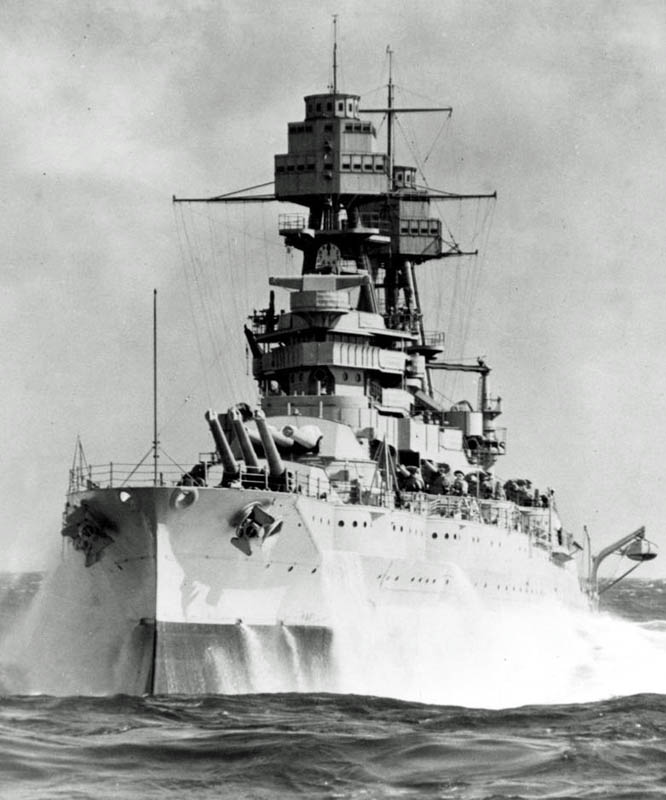

USS Arizona (BB-39), early 1941.

Click on any image to zoom.

Origins

A Pacific Fleet was created in 1907 when the Asiatic Squadron and the Pacific Squadron were combined. In 1910, the ships of the First Squadron were organized back into a separate Asiatic Fleet. The General Order 94 of 6 December 1922 organized the United States Fleet, with the Battle Fleet as the Pacific presence. Until May 1940, the Battle Fleet was stationed on the west coast of the United States (primarily at San Diego). During the summer of that year, as part of the U.S. response to Japanese expansionism, it was instructed to take an "advanced" position at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Long-term basing at Pearl Harbor was so strongly opposed by the commander, Admiral James O. Richardson, that he personally protested in Washington. Political considerations were thought sufficiently important that he was relieved by Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who was in command at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Pacific Fleet was formally recreated on 1 February 1941. On that day General Order 143 split the United States Fleet into separate Atlantic, Pacific, and Asiatic Fleets.

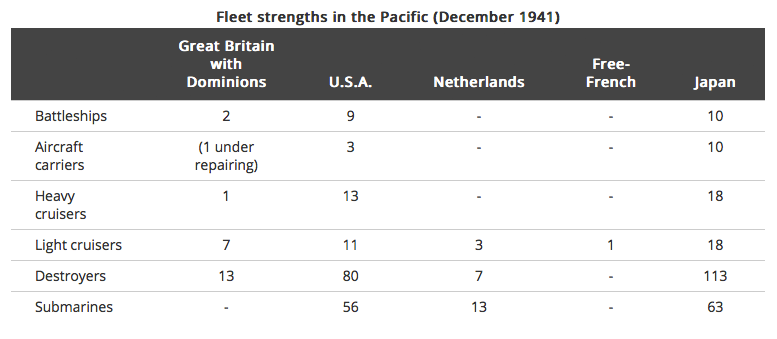

The Navy Expands

In December 1941, the fleet consisted of nine battleships, three aircraft carriers, 12 heavy cruisers, eight light cruisers, 50 destroyers, 33 submarines, and 100 patrol bombers. This was approximately the fleet's strength at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. That day, the Japanese Combined Fleet carried out the attack on Pearl Harbor, drawing the United States into World War II in the Pacific. The Pacific Fleet's Battle Line took the brunt of the attack, with two battleships destroyed, two salvageable but requiring lengthy reconstruction, and four more lightly to moderately damaged, forcing the U.S. Navy to rely primarily on aircraft carriers and submarines for many months afterward.

When the attack on Pearl Harbor took place, all three carriers were absent - Saratoga was in San Diego collecting her air group following a major refit, Enterprise was en route back to Hawaii following a mission to deliver aircraft to Wake Island, while Lexington had just departed on a similar mission to Midway.

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

The Pacific Fleet: December 1941

On 7 December, the Fleet consisted of the Battle Force, Scouting Force, Base Force, Amphibious Force (ComPhibPac), Cruiser Force (COMCRUPAC), Destroyer Force (COMDESPAC), and the Submarine Force (COMSUBPAC).

At the beginning of the Pacific War, the United States Pacific Fleet based at Pearl Harbor consisted of nine battleships and three aircraft carriers. After the attack on 7 December the Japanese sunk four battleships, severely damaged three others, and one was beached.

In all, 2,403 Americans were killed and 1,176 wounded. Fortunately, the three fleet carriers, Enterprise, Lexington and Saratoga were absent from Pearl Harbor and survived unscathed along with five cruisers and twenty-nine destroyers to form the nucleus of the new expanded Pacific Fleet.

Naval building had been increasing in tempo since the ‘Two Ocean’ Act of 1940, but the Navy was hard-put to match the Japanese forces in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. The immediate reaction of the United States was to construct, with great speed, four fast carriers of the Essex-class (which carried 90 aircraft each) and five carriers carrying 40 aircraft each.

USS Essex (CV-9) deck loaded with aircraft fighters during World War II.

Post-Attack Ship Salvage

During the weeks following the Japanese raid, a great deal of repair work was done by the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, assisted by tenders and ships' crewmen. These efforts, lasting into February 1942, put the battleships Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Tennessee; cruisers Honolulu, Helena, and Raleigh; destroyers Helm and Shaw, seaplane tender Curtiss, repair ship Vestal and the floating drydock YFD-2 back into service, or at least got them ready to steam to the mainland for final repairs. The most seriously damaged of these ships, Raleigh and Shaw, were returned to active duty by mid-1942.

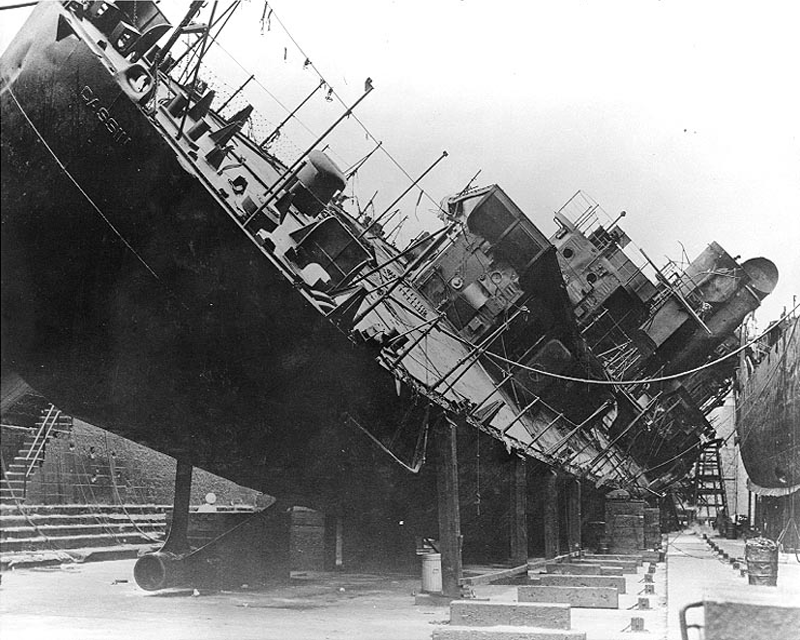

Five more battleships, two destroyers, a target ship and a minelayer were sunk, or so severely damaged as to represent nearly total losses. These required much more extensive work just to get them to a point where repairs could begin. Starting in December 1941 and continuing into February 1942, the Navy Yard stripped the destroyers Cassin and Downes of servicable weapons, machinery and equipment. This materiel was sent to California, where it was installed in new hulls. These two ships came back into the fleet in late 1943 and early 1944.

Capsized USS Cassin (DD-372) – a Mahan-class destroyer – under salvage at Pearl Harbor, 23 January 1942.

To work on the remaining seven ships, all of them sunk, a salvage organization was formally established a week after the raid to begin what would clearly be a huge job. Commanded from early January 1942 by Captain Homer N. Wallin, previously a member of the Battle Force Staff, this Salvage Division labored hard and productively for over two years to refloat five ships and remove weapons and equipment from the other two. Among its accomplishments were the refloating of the battleships Nevada in February 1942, California in March, and West Virginia in June, plus the minelayer Oglala during April-July 1942. After extensive shipyard repairs, these four ships were placed back in the active fleet in time to help defeat Japan. The Salvage Division also righted and refloated the capsized battleship Oklahoma, partially righted the capsized target ship Utah and recovered materiel from the wreck of the battleship Arizona. However, these three ships were not returned to service, and the hulls of the last two remain in Pearl Harbor to this day.

All this represented one of history's greatest salvage jobs. Seeing it to completion required that Navy and civilian divers spend about 20,000 hours underwater in about 5,000 dives. Long and exhausting efforts were expended in recovering human remains, documents, ammunition and other items from the oil-fouled interiors of ships that had been under water for months. Uncounted hours went into cleaning the ships and otherwise getting them ready for shipyard repair. Much of this work had to be carried out in gas masks, to guard against the ever-present risk of toxic gasses, and nearly all of it was extremely dirty.

USS Oklahoma being righted to about 30 degrees, on 29 March 1943, while she was under salvage at Pearl Harbor. She had capsized and sunk during the 7 December 1941 Japanese air raid. Naval Air Station Ford Island is in the background.

Salvage of the USS Oklahoma (BB-37)

The righting and refloating of the capsized battleship Oklahoma was the largest of the Pearl Harbor salvage jobs, and the most difficult. Since returning this elderly and very badly damaged warship to active service was not seriously contemplated, the major part of the project only began in mid-1942, after more immediately important salvage jobs were completed. Its purpose was mainly to clear an important mooring berth for further use, and only secondarily to recover some of Oklahoma's weapons and equipment.

The first task was turning Oklahoma upright. During the latter part of 1942 and early 1943, an extensive system of righting frames (or "bents") and cable anchors was installed on the ship's hull, twenty-one large winches were firmly mounted on nearby Ford Island, and cables were rigged between ship and shore. Fuel oil, ammunition and some machinery were removed to lighten the ship. Divers worked in and around her to make the hull as airtight as possible. Coral fill was placed alongside her bow to ensure that the ship would roll, and not slide, when pulling began. The actual righting operation began on 8 March and continued until mid-June, with rerigging of cables taking place as necessary as the ship turned over.

To ensure that the ship remained upright, the cables were left in place during the refloating phase of the operation. Oklahoma's port side had been largely torn open by Japanese torpedos, and a series of patches had to be installed. This involved much work by divers and other working personnel, as did efforts to cut away wreckage, close internal and external fittings, remove stores and the bodies of those killed on 7 December 1941. The ship came afloat in early November 1943, and was drydocked in late December, after nearly two more months of work.

Once in Navy Yard hands, Oklahoma's most severe structural damage was repaired sufficiently to make her watertight. Guns, some machinery, and the remaining ammuniton and stores were taken off. After several months in Drydock Number Two, the ship was again refloated and moored elsewhere in Pearl Harbor. She was sold to a scrapping firm in 1946, but sank in a storm while under tow from Hawaii to the west coast in May 1947.

New Construction

The weight of American naval effort was directed to the Pacific and, in this theatre of war, naval power, usually expressed in terms of carrier-based aircraft, was to be absolutely crucial. The great influence of American manufacturing capacity was nowhere more clearly shown than in the Pacific naval battles, where the US superiority in building aircraft carriers quickly became the decisive factor.

While not “rebuilding”, the US Navy started adding to the fleet before the Pearl Harbor attack and declaration of war in December of 1941.

Two North Carolina-class battleships were started in 1937 and commissioned in May and June of 1941. Four of the follow-on South Dakota-class were started in 1939 with several commissioned by mid-1942. The first Iowa-class battleships (6 ordered, 4 built) were laid down in 1940 though they were commissioned starting in early 1943.

For aircraft carriers the Naval Expansion Act of Congress passed on 17 May 1938, the first Essex-class was laid down in 1941, but the orders for the first 11 were placed before the Pearl Harbor attack.

The build-up was not just capital ships. The Brooklyn-class light cruisers were first ordered in 1933 with the first commissioned in 1937. Similarly with the destroyer build up with the Benson/Gleaves first ordered in 1938, and commissioned starting in 1938.

Some of this buildup was due to the the “battleship building holiday” of the Washington Treaty and follow on treaties ending in 1935, and invoking the escalator clause when Italy and Japan did not sign (or withdrew) from the last of those treaties. It was also a response to other country’s navies launching new more powerful ships and the related awareness that the USA might have to fight another war.

However, once war was declared and US industry got into a “war footing” the rate of naval construction was vastly increased. Warships take longer to build than Liberty ships, but the pace of ships being commissioned was very high starting in 1943 (and to be commissioned in 1943, the ship had to be ordered and construction started (laid down) well before that.

Long Range Shipbuilding Program

The Long Range Shipbuilding program was implemented by the U.S. Maritime Commission shortly after its establishment in 1937 as part of the mandate of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 which stated that:

United States shall have a merchant marine

(a) sufficient to carry its domestic water-borne commerce and a substantial portion of the water-borne export and import foreign commerce of the United States and to provide shipping service on all routes essential for maintaining the flow of such domestic and foreign water-borne commerce at all times

(b) capable of serving as a naval and military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency,

(c) owned and operated under the United States flag by citizens of the United States insofar as may be practicable, and

(d) composed of the best-equipped, safest, and most suitable types of vessels, constructed in the United States and manned with a trained and efficient citizen personnel. It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States to foster the development and encourage the maintenance of such a merchant marine.

Prior to the passage of the act, the U.S.'s merchant fleet was primarily made up of ships which had been built as part of the Emergency Fleet Program at the end of World War I. Because of technological advances in hull construction and propulsion machinery, these ships were rapidly becoming obsolete and non-competitive in the commercial market and of limited value to the Navy as auxiliary support vessels. Additionally, U.S. shipyards had been suffering atrophy from more than 15 years of little to no new construction with either Navy nor commercial orders and it was felt by the Roosevelt Administration that rebuilding the commercial shipbuilding capacity in the U.S. was in the nation's strategic interest.

Videos

How A Cargo Ship Helped Win WW2: The Liberty Ship Story

During World War Two, hundreds of cargo ships raced across the Atlantic in an effort to keep Britain supplied. But these ships were being sunk by German U-boats, warships and aircraft. In 1940 alone, over a thousand allied ships were lost on their way to Britain.

Liberty Ship - Victory Ship Comparison

This is a look at the main differences between the Liberty ships and the later Victory ships.

Sources: Wikipedia and The Naval History and Heritage Command

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II. Though British in conception, the design was adapted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Mass-produced on an unprecedented scale, the Liberty ship came to symbolize U.S. wartime industrial output.

Maritime Commission

In order to remedy this situation and to facilitate the mission given to it by the act, the Maritime Commission devised a program to build 500 new design merchant freighters powered with either steam turbines or diesels. The 500 total ships were to be built over a 10-year period and contracts for their construction went to both established and new shipyards on the East, West and Gulf Coasts. The new ships would be broken into two groups. First were those constructed to contracts placed by the individual shipping companies to their own designs but where the construction differential between a US and foreign yards to be subsidized by the Maritime Commission. The second group were ships built to standard designs of the Commission and where the contract for the construction of the ships would be to Federal Government's account. It was this shipbuilding effort which became known as the Long Range Program. It was intended that this latter group of ships would be chartered to commercial operators who would use the ships in peacetime but that the ships would be available for use by the Navy in wartime. These included the type C1 ships, type C2 ships and type C3 ships.

Those ships, like their predecessors in the prewar Long Range Program, were built to government contract and then chartered to commercial shipping firms or transferred to the Navy for use as auxiliaries.

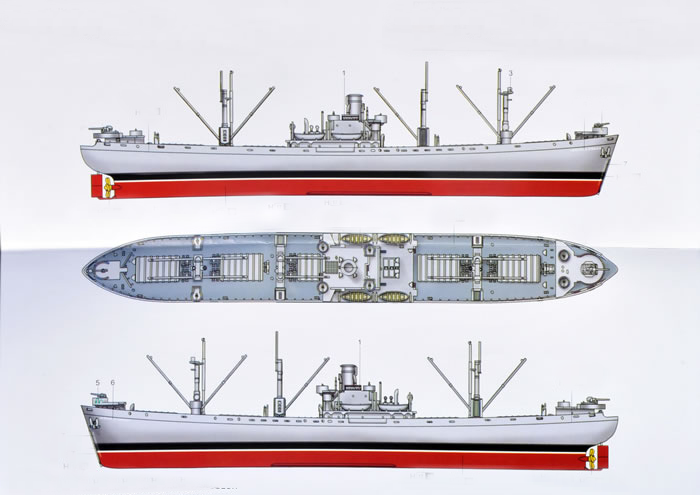

U.S. Maritime Commission C1 standard type cargo vessel

U.S. Maritime Commission C2 standard type cargo vessel

U.S. Maritime Commission C3 standard type cargo vessel

USS Elmore (APA-42) was a Maritime Commission type (C3-S-A2) hull built under a Maritime Commission contract (MC Hull 390) at Ingalls Shipbuilding Corp., Pascagoula, MS.

Since war appeared to be drawing closer by the year, the Long Range Program grew in importance and in 1940 was accelerated to deliver more of the 500 planned ships sooner than originally scheduled. The fall of France in May 1940 was a watershed for the Commission and the Long Range Program for when Germany was able to move its U-Boat bases to the Brittany coast of France, the Battle of the Atlantic turned drastically against Great Britain's attempts to keep her supply lines open. With losses of merchant vessels far exceeding the ability to replace then in UK shipyards, the British Merchant Shipping Mission arrived in North America with the intention of ordering replacement cargo vessels in the U.S. and Canada. Permission to do so in the U.S. was sought and granted by the Maritime Commission for the U.K. to fund the construction of two new shipyards in South Portland, Maine and Richmond, California and for each to build 30 vessels to UK design. This was the genesis of the Emergency Shipbuilding program which would soon eclipse the Long Range Program in both scope and scale.

Although it was clear that the Emergency Program would be much larger than the Long Range Program, the Commissioners led by Admiral Emory S. Land fought to ensure that the smaller program not be allowed to whither to nothing. All five members of the Maritime Commission realized that the war would come to an end someday and the Liberty ships would not be capable of fulfilling what would be required of the postwar U.S. Merchant fleet. Although by mid-1941 ships were no longer being ordered by commercial operators, ships of the standard designs continued to be ordered by the Commission. As shipbuilding accelerated in 1941 with more ships being ordered for both the Long Range and Emergency Programs, by March 1942 the oversight of shipbuilding was decentralized by the Maritime Commission into four regional offices, one on each of the three seacoasts and the last for the Great Lakes region. With this move the Long Range Program was combined with the Emergency Program for the duration as both programs were supervised as one by the individual Regional offices.

Emergency Shipbuilding Program

The Emergency Shipbuilding Program (late 1940-September 1945) was a United States government effort to quickly build simple cargo ships to carry troops and material to allies and foreign theatres during World War II. Run by the U.S. Maritime Commission, the program built almost 6,000 ships.

With the defense of both the U.S. and its overseas possessions along with a very strong national interest in assisting Britain in its struggle to keep its supply lines open to both North America and its overseas Colonies, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced what was to become known as the Emergency Shipbuilding Program on January 3, 1941 for the construction of 200 ships very much similar to those being built for the British. He designated that the Program be implemented and administered by the Maritime Commission which since 1937 had been the Federal government department tasked with Merchant Marine development and which had worked very closely with the British Mission in placing its 60 ship order. Immediately the Commission authorized that the two yards building for the British build ships for the U.S. upon completion of their current contracts.

The Maritime Commission also funded the yards to add building ways and realizing that more than two yards would be needed for the program they were expecting to enter into contracts to build new shipyards on the Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific coasts of the U.S. In this first wave of expansion seven additional yards were added to those in Maine and California and like those yards were to be for the sole purpose of building only the Emergency type of ships. While all the yards were to be built by private contractors and operated by commercial shipbuilding companies, the new yards were financed by the Maritime Commission with funds authorized by Congress and thus owned by Federal Government.

The Emergency Ships

The ships which all the yards were contracted to build were first designated by the Maritime Commission as EC2-S-C1 but because they were designed for capacity and rapid construction as opposed to speed and gracefulness lacked streamlined appearance of the more modern ship designs of the Maritime Commission such as the standard freighters type C2 ships or type C3 ships, the President had declared them to be "dreadful looking objects" and from that the term "Ugly Duckling" became the unofficial name for the emergency vessels. It was not until April 1941 that the vessels collectively were being officially referred to as the "Liberty Fleet" ships and not long after the term "Liberty Ship" became the standard name applied to all vessels of the class.

Like their British counterparts, the Ocean-class, the Liberty ships were of a 5 hatch design of approximately 10000 tons loaded displacement powered by the same size triple expansion reciprocating steam engines but using more modern oil fired water-tube boilers. Overall they were somewhat antiquated for the era and there was some quiet objection on the part of some of the members of the Maritime Commission to devoting so many valuable resources to their construction. Some believed that fewer although faster ships would be able to move as much cargo since with their added speed they could make more voyages in any given year, but faster and more complex ships required more time to build and more importantly, required steam turbines in order to gain the additional speed.

In 1941, the manufacturers of steam turbines in the U.S., companies such as General Electric, Westinghouse and Allis-Chalmers, did not have adequate production capacity to build all the turbines demanded by the Navy or for the Maritime Commissions standard dry cargo ships or tankers it was intending to still build. In the end, it was decided that what the looming war was going to require were ships which could be built quickly using prefabrication by workers relatively unskilled in shipbuilding and in greatest numbers with the available resources. With that, the Liberty ship was adopted as the only emergency type to be built and thus shared by all of the new emergency shipyards. While all the new yards were able to get their first keels laid in a very short period of time, the first of the Liberty ships to be launched was the SS Patrick Henry which rolled down the ways at the Bethlehem-Fairfield yard on September 27, 1941.

Liberty ship Joseph M. Terrel at Brunswick, GA c. 1944

The December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent entry of the U.S. into the war caused all previously established production schedules to be further revised dramatically upward. With the need to assist Britain replace its lost tonnage and to provide adequate ships to the Army to transport troops and supplies to foreign theaters, in January 1942 President Roosevelt asked that 8 million tons of shipping be built in 1942 and 10 million in 1943.

While this rapid expansion was taking place, all other defense industries were also in a maximum production mode to accommodate the orders being placed by the Federal Government for all other manner of military equipment which included the massive wartime Naval Expansion program begun in 1940 with the passage of the Two Ocean Navy Act. So much growth in demand happening simultaneously in industries sharing common materials inevitably led to shortages in steel, propulsion machinery and most all other manner of ship equipment. In many cases the shortages affected the Emergency Program more than it did the Navy's since its programs were deemed of higher priority in the eyes of the many wartime boards set up for deciding on where scarce resources would be allocated. All along the way, the Navy made claim to as much of the raw materials, steel, machinery, manufacturing plant allocations, and labor that it could get.

For the most part, this imbalance occurred because the Maritime Commission lacked the clout that the Military Branches possessed and that clout ultimately swayed entities such as the Supply Priorities and Allocation Board (SPAB) to decide in favor of the Navy's demands. This disproportionate allocation regime often left the Maritime Commission without the resources needed to accomplish the goals established for it by President Roosevelt and it was only through direct appeal to FDR by Admiral Land that enough of the critical resources made it to the Emergency Program.

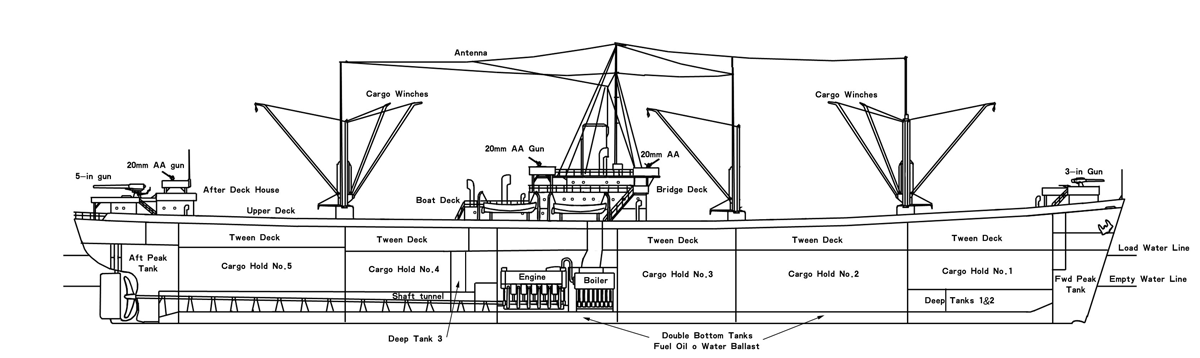

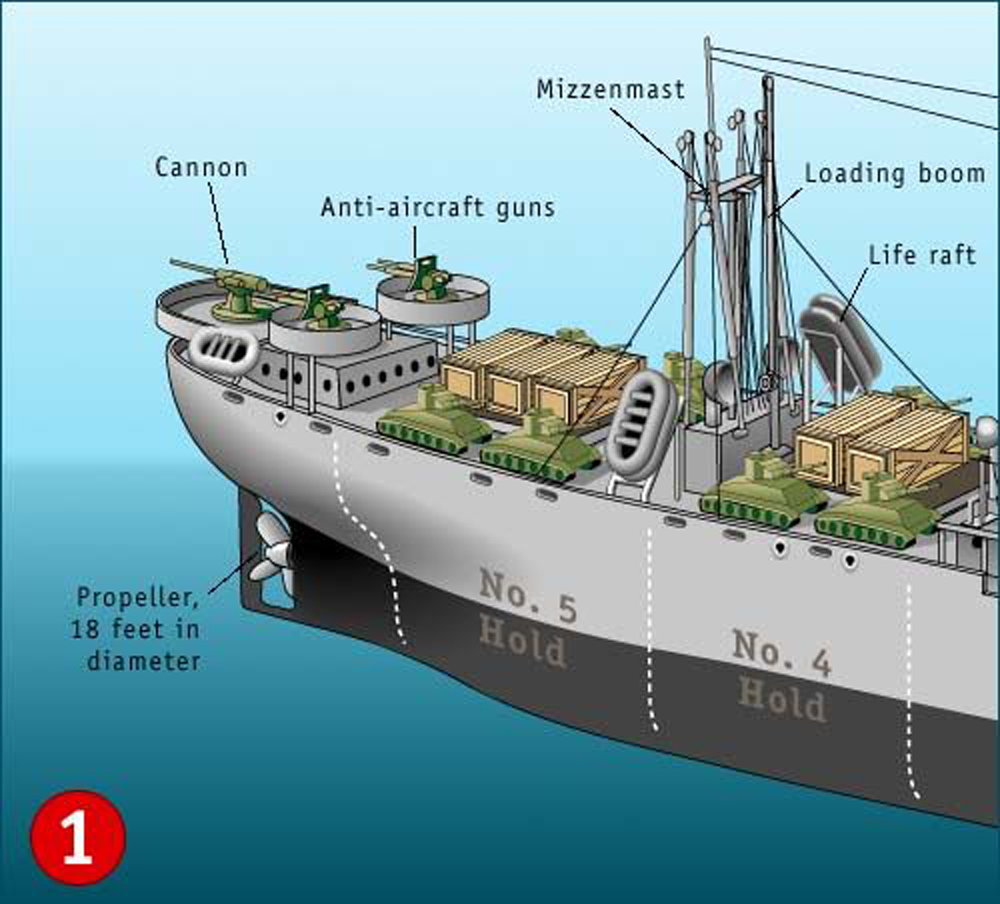

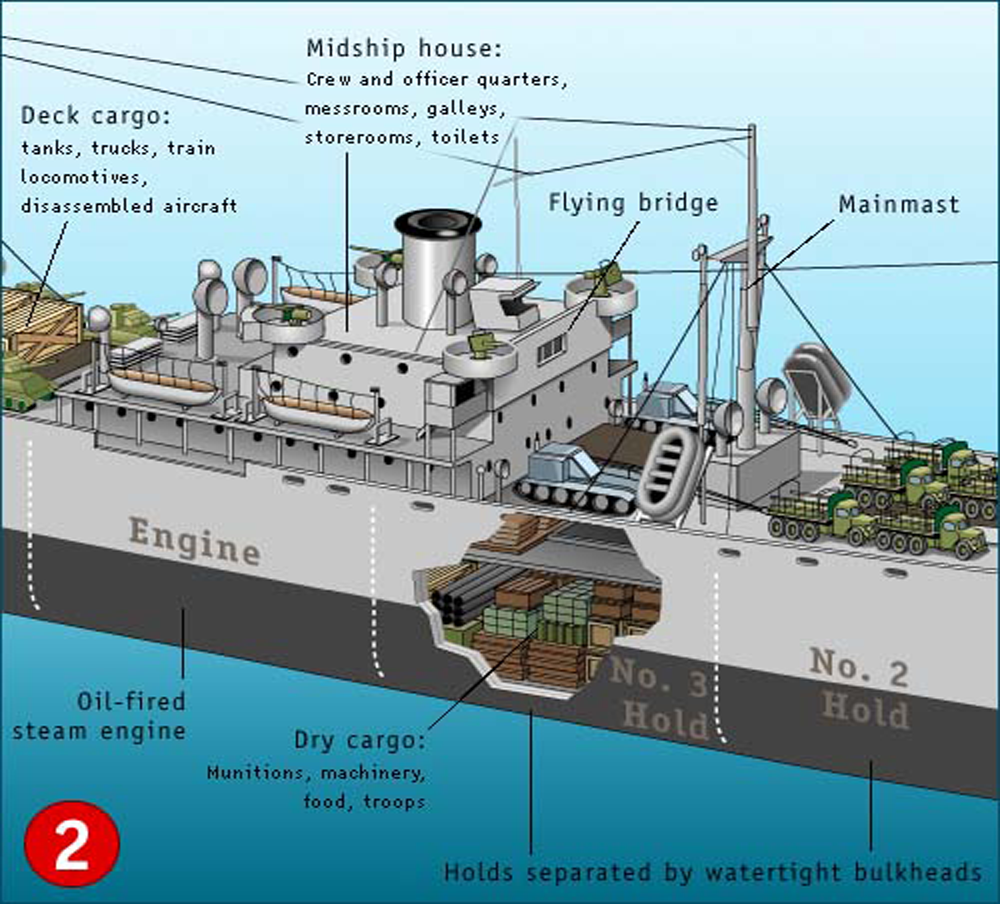

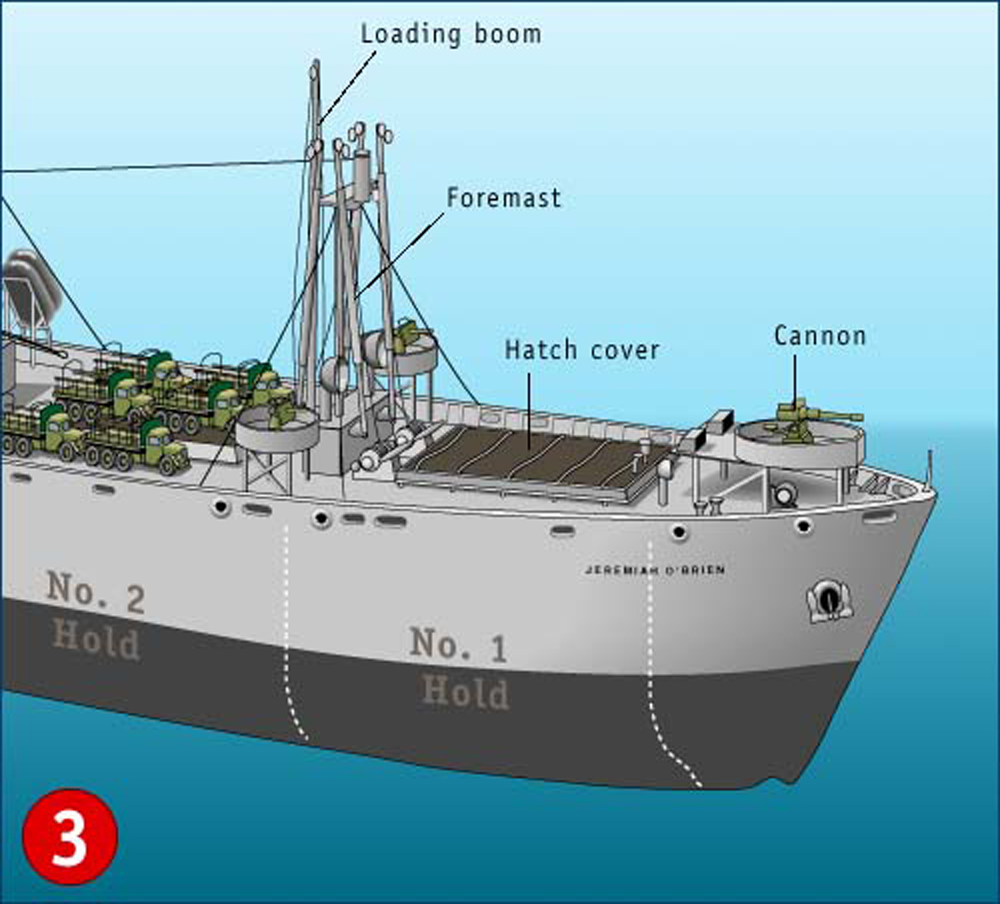

Liberty Ship diagram

Liberty Production

By the 2nd half of 1942 the yards contracted in the first waves of expansion were fully built and those yards had completed three or more ships per building way. The time for building the ships fell dramatically as experience was gained by the workers in their jobs and by the management in each yard in the most effective means to do the construction. One factor which played a major part in getting the productivity so high was the use of welding and prefabrication in which large sections of each ship's hull or superstructure would be built off the building ways and then moved into position only when the assemblers were ready. This method became so efficient that a single Liberty ship to be fully assembled, launched, outfitted and delivered went from a program average of almost 240 days at the beginning of 1942 to only 56 days at the end of the year. At the most productive yards on the West Coast, Oregon Ship and Richmond #2, the time a single vessel spent on the ways before launching was only a little more than two weeks. Two particular ships were built in record breaking amounts of time. First in September 1942 the Liberty ship SS Joseph N. Teal was built Oregon Shipbuilding in 10 days. Two months later in November at Richmond yard #2, the SS Robert E. Peary was launching in only 4 days, 15 hours, 29 minutes from the time her keel was laid. While not every ship met or repeated these feats during the remainder of World War II, these "stunt" ships came only a little more than one year after the first ships ordered as part of the Emergency Program were launched themselves.

Click on any image to zoom.

Coming into play during this time was a de facto combining of both the Long Range Shipbuilding Program with the Emergency and oversight of the yards became decentralized into four separate Regional Directors. The Programs added together at the peak of output in mid 1943 ultimately employed 650,000 workers in all the Maritime Commission contracted yards and unknown tens of thousands more manufacturing the components need to assemble the ships. It was not without hurdles which needed to be overcome to reach the levels of production achieved. The Maritime Commission struggled throughout 1942 and the first half of 1943 to get enough steel allocated to it from the War Production Board. With plate mills around the country running beyond their normal capacity, the demand for plate by all war industries, but especially the Navy's shipbuilding was still more than could be made. It was not until the 2nd half of 1943 when new or expanded plate production facilities came online, that the shortage to steel plate abated. Additionally, there were constant shortages of many of the parts which were shared between Navy and Merchant vessels such as pumps and valves. Still with all the hurdles faced, the Maritime Commission and the yards contracted to it were able to deliver 8 million tons of shipping to the war effort by the end of 1942 and more than 12 million tons in 1943.

Victory Ships

By the time that Liberty ship construction was reaching its maximum output rate in early 1943, it became clear to military planners and the Maritime Commission that it was preferable to slow the rate of the building Liberty class vessels and begin building a class with a higher operating speed. What was decided was to begin building a class no larger than the Liberty class but with steam turbine propulsion. The shortage of turbines having been relieved by the expansion of turbine manufacturing capacity during 1941 and 1942. Beginning in March 1943, with enough turbines, the Victory ship or VC2 type cargo vessels were contracted for at all of the West Coast yards which had been previously building Liberties as well as at the Bethlehem-Fairfield yard. The first of the new class, the SS United Victory being completed and delivered at Oregon Shipbuilding in February 1944. Although initial deliveries were slow—only 15 had been delivered by May 1944—by the end of the war 531 had been constructed.

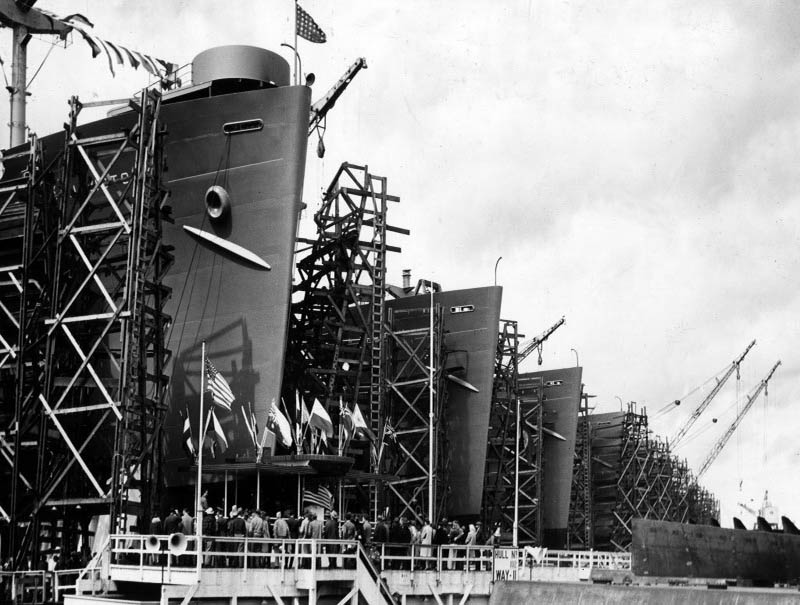

Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation, Victory ships 1944

The Navy projected a need for a substantial number of new attack transports for the planned invasion of Japan. With the ability to quickly produce the new Victory-class ships, the Navy authorized this class to serve as the basis of the Haskell-class transports.

The Haskell-class, Maritime Commission standard type VC2-S-AP5, is a sub‑type of the Victory ship design. 117 were launched in 1944 and 1945, with 14 more being finished as another VC2 type or canceled. These were built by the War Shipping Administration under the Emergency Shipbuilding program.

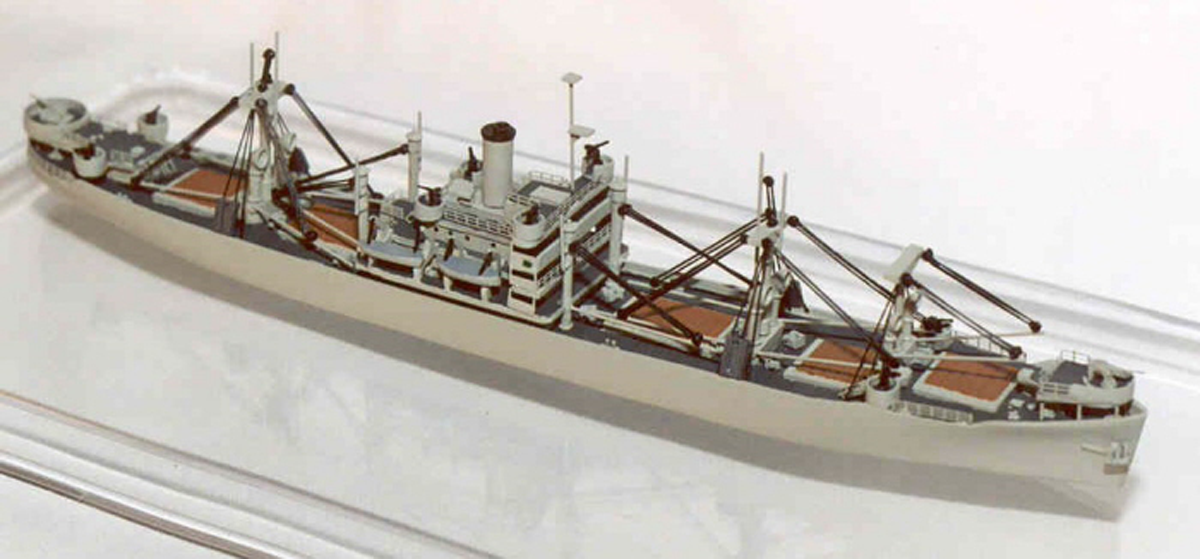

Model of a Victory ship

The AP5 type attack transports were named after United States counties, without "Victory" in their name, with the exception of USS Marvin H. McIntyre, which was named after President Roosevelt's late personal secretary.

The Haskells were very active in the Pacific Theater of Operations, landing Marines and Army troops and transporting casualties at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. These ships appeared in large numbers in early 1945 and would have been a significant factor in the planned invasion of Japan, scheduled for 1 November 1945. Ships of the class were among the first Allied ships to enter Tokyo Bay at the end of World War II, landing the first occupation troops at Yokosuka. After the end of World War II, most participated in Operation Magic Carpet, the massive sealift of US personnel back to the United States. A few of the Haskell-class were reactivated for the Korean War, with some staying in service into the Vietnam War.

Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation's USS Glynn (APA-239), a Haskell-class APA, was based on the Victory ship.