Magic: Breaking the Japanese Code

Magic was an Allied cryptanalysis project during World War II. The U.S. used the codename "Magic" for its decrypts from Japanese sources including the so-called "Purple" cipher.

Codebreaking

Magic was set up to combine the US government's cryptologic capabilities in one organization dubbed the Research Bureau. Intelligence officers from the Army and Navy (and later civilian experts and technicians) were all under one roof. Although they worked on a series of codes and cyphers, their most important successes involved RED, BLUE, and PURPLE.

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well. Every Japanese code was eventually broken, and the intelligence gathered made possible such operations as the victorious American ambush of the Japanese Navy at Midway (JN-25b) and the shooting down of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in Operation Vengeance.

RED

In 1923, a US Navy officer acquired a stolen copy of the Secret Operating Code codebook used by the Japanese Navy during World War I. Photographs of the codebook were given to the cryptanalysts at the Research Desk and the processed code was kept in red-colored folders (to indicate its Top Secret classification). This code was called "RED".

BLUE

In 1930, the Japanese government created a more complex code that was codenamed BLUE, although RED was still being used for low-level communications. It was quickly broken by the Research Desk no later than 1932. US Military Intelligence Signal Intelligence listening stations began monitoring command-to-fleet, ship-to-ship, and land-based communications.

PURPLE

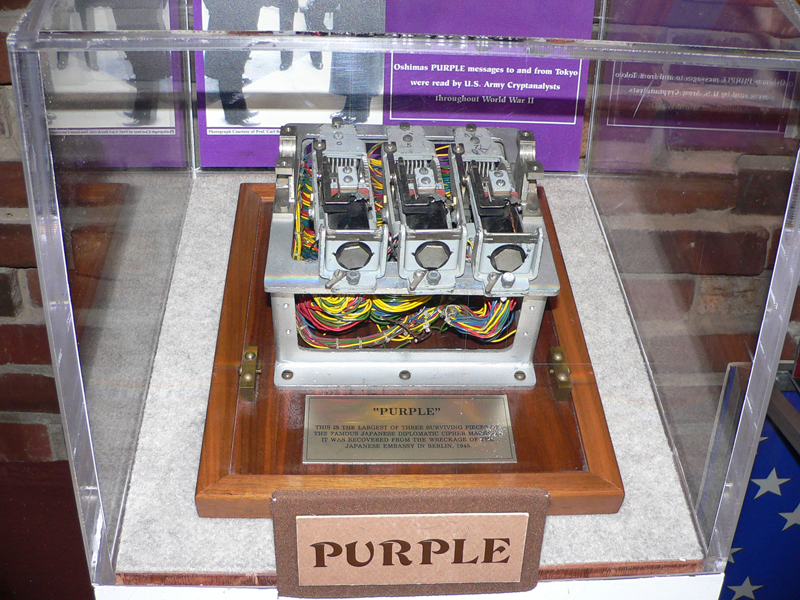

After Japan's ally Germany declared war in the fall of 1939, the German government began sending technical assistance to upgrade their communications and cryptography capabilities. One part was to send them modified Enigma machines to secure Japan's high-level communications with Germany. The new code, codenamed PURPLE (from the color obtained by mixing red and blue), was baffling.

PURPLE, like Enigma, the German coding system, began its communications with the same line of code but then became an unfathomable jumble. Codebreakers tried to break PURPLE communiques by hand but found they could not. Then the codebreakers realized that it was not a manual additive or substitution code like RED and BLUE, but a machine-generated code similar to Germany's Enigma cipher. Decoding was slow and much of the traffic was still hard to break. By the time the traffic was decoded and translated, the contents were often out of date.

A reverse-engineered machine created in 1939 by a team of technicians led by William Friedman and Frank Rowlett could figure out some of the PURPLE code by replicating some of the settings of the Japanese Enigma machines. This sped up decoding and the addition of more translators on staff in 1942 made it easier and quicker to decipher the traffic intercepted.

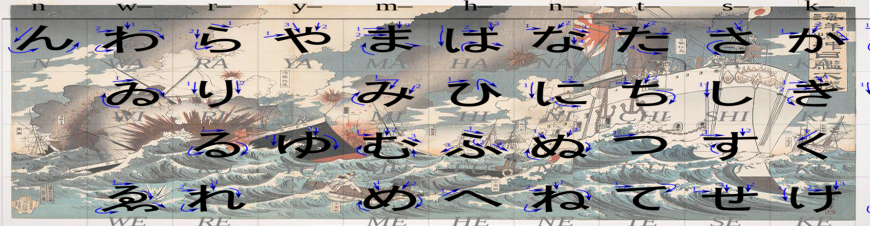

Japanese “ENIGMA” type rotor cipher

PURPLE Traffic

The Japanese Foreign Office used a cipher machine to encrypt its diplomatic messages. The machine was called "PURPLE" by U.S. cryptographers. A message was typed into the machine, which enciphered and sent it to an identical machine. The receiving machine could decipher the message only if set to the correct settings, or keys. American cryptographers built a machine that could decrypt these messages.

The PURPLE machine itself was first used by Japan in 1940. U.S. and British cryptographers had broken some PURPLE traffic well before the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, the PURPLE machines were used only by the Foreign Office to carry diplomatic traffic to its embassies. The Japanese Navy used a completely different crypto-system, known as JN-25.

U.S. analysts discovered no hint in PURPLE of the impending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor; nor could they, as the Japanese were very careful not to discuss their plan in Foreign Office communications. In fact, no detailed information about the planned attack was even available to the Japanese Foreign Office, as that agency was regarded by the military, particularly its more nationalist members, as insufficiently "reliable". U.S. access to private Japanese diplomatic communications (even the most secret ones) was less useful than it might otherwise have been because policy in prewar Japan was controlled largely by military groups like the Imperial Way Faction, and not by the Foreign Office. The Foreign Office itself deliberately withheld from its embassies and consulates much of the information it did have, so the ability to read PURPLE messages was less than definitive regarding Japanese tactical or strategic military intentions.

U.S. cryptographers had decrypted and translated the 14-part Japanese diplomatic message breaking off ongoing negotiations with the U.S. at 1 p.m. Washington time on 7 December 1941, even before the Japanese Embassy in Washington could do so. As a result of the deciphering and typing difficulties at the embassy, the note was delivered late to American Secretary of State Cordell Hull. When the two Japanese diplomats finally delivered the note, Hull had to pretend to be reading it for the first time, even though he already knew about the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Throughout the war, the Allies routinely read both German and Japanese cryptography. The Japanese Ambassador to Germany, General Hiroshi Ōshima, often sent priceless German military information to Tokyo. This information was routinely intercepted and read by Roosevelt, Churchill and Eisenhower. According to Lowman, "The Japanese considered the PURPLE system absolutely unbreakable.... Most went to their graves refusing to believe the [cipher] had been broken by analytic means.... They believed someone had betrayed their system."

Remnant of the Japanese Purple cipher recovered from their bombed-out embassy in Berlin in 1945.

Distribution Prior to Pearl Harbor

Even so, the diplomatic information was of more limited value to the U.S. because of its manner and its description. "Magic" was distributed in such a way that many policy-makers who had need of the information in it knew nothing of it, and those to whom it actually was distributed (at least before Pearl Harbor) saw each message only briefly, as the courier stood by to take it back, and in isolation from other messages (no copies or notes being permitted). Before Pearl Harbor, they saw only those decrypts thought "important enough" by the distributing Army or Navy officers. Nonetheless, being able to read PURPLE messages gave the Allies a great advantage in the war; for instance, the Japanese ambassador to Germany, Baron Hiroshi Ōshima, produced long reports for Tokyo which were enciphered on the PURPLE machine. They included reports on personal discussions with Adolf Hitler and a report on a tour of the invasion defenses in Northern France (including the D-Day invasion beaches). General Marshall said that Ōshima was "our main basis of... information regarding Hitler's intentions in Europe".

Dewey and Marshall

During the 1944 presidential election, Republican candidate Thomas Dewey threatened to make Pearl Harbor a campaign issue, until General Marshall sent him a personal letter which said, in part:

To explain the critical nature of this set-up, which would be wiped out in an instant if the least suspicion were aroused regarding it, the Battle of Coral Sea was based on deciphered messages and therefore our few ships were in the right place at the right time. Further, we were able to concentrate our limited forces to meet their naval advance on Midway when otherwise we almost certainly would have been some 3000 miles out of place. We had full information on the strength of their forces.

Dewey promised not to raise the issue, and kept his word.

Post-War Debates

The break into the PURPLE system, and into Japanese messages generally, was the subject of acrimonious hearings in Congress post-World War II in connection with an attempt to decide who, if anyone, had allowed the disaster at Pearl Harbor to happen and who therefore should be blamed. During those hearings the Japanese learned, for the first time, the PURPLE cypher system had been broken. They had been continuing to use it, even after the War, with the encouragement of the American Occupation Government. Much confusion over who in Washington or Hawaii knew what and when, especially as "we were decrypting their messages," has led some to conclude "someone in Washington" knew about the Pearl Harbor attack before it happened, and, since Pearl Harbor was not expecting to be attacked, the "failure to warn Hawaii one was coming must have been deliberate, since it could hardly have been mere oversight". However, PURPLE was a diplomatic, not a military code; thus, only inferences could be drawn from PURPLE as to specific Japanese military actions.

History

When PURPLE was broken by the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS), several problems arose for the Americans: who would get the decrypts, which decrypts, how often, under what circumstances, and crucially (given interservice rivalries) who would do the delivering. Both the U.S. Navy and Army were insistent they alone handle all decrypted traffic delivery, especially to highly placed policy makers in the U.S. Eventually, after much to-ing and fro-ing, a compromise was reached: the Army would be responsible for the decrypts on one day, and the Navy the next.

The distribution list eventually included some — but not all — military intelligence leaders in Washington and elsewhere, and some — but, again, not all — civilian policy leaders in Washington. The eventual routine for distribution included the following steps:

- the duty officer (Army or Navy, depending on the day) would decide which decrypts were significant or interesting enough to distribute

- they would be collected, locked into a briefcase, and turned over to a relatively junior officer (not always cleared to read the decrypts) who would 'make the rounds' to the appropriate offices.

- no copies of any decrypts were left with anyone on the list. The recipient would be allowed to read the translated decrypt, in the presence of the distributing officer, and was required to return it immediately upon finishing. Before the beginning of the second week in December 1941, that was the last time anyone on the list saw that particular decrypt.

Decryption Process

There were several prior steps needed before any decrypt was ready for distribution:

- Interception. The Japanese Foreign Office used both wireless transmission and cables to communicate with its off shore units. Wireless transmission was intercepted (if possible) at any of several listening stations (Hawaii, Guam, Bainbridge Island in Washington state, Dutch Harbor on an Alaska island, etc.) and the raw cypher groups were forwarded to Washington, D.C. Eventually, there were decryption stations (including a copy of the Army's PURPLE machine) in the Philippines as well. Cable traffic was (for many years before late 1941) collected at cable company offices by a military officer who made copies and started them to Washington. Cable traffic in Hawaii was not intercepted due to legal concerns until David Sarnoff of RCA agreed to allow it during a visit to Hawaii the first week of December 1941. At one point, intercepts were being mailed to (Army or Navy) Intelligence from the field.

- Deciphering. The raw intercept was deciphered by either the Army or the Navy (depending on the day). Deciphering was usually successful as the cipher had been broken.

- Translation. Having obtained the plain text, in Latin letters, it was translated. Because the Navy had more Japanese-speaking officers, much of the burden of translation fell onto the Navy. And because Japanese is a difficult language, with meaning highly dependent upon context, effective translation required not only fluent Japanese, but considerable knowledge of the context within which the message was sent.

- Evaluation. The translated decrypt had to be evaluated for its intelligence content. For example, is the ostensible content of the message meaningful? If it is, for instance, part of a power contest within the Foreign Office or some other part of the Japanese government, its meaning and implications would be quite different from a simple informational or instructional message to an Embassy. Or, might it be another message in a series whose meaning, taken together, is more than the meaning of any individual message. Thus, the fourteenth message to an Embassy instructing that Embassy to instruct Japanese merchant ships calling at that country to return to home waters before, say, the end of November would be more significant than a single such message meant for a single ship or port. Only after having evaluated a translated decrypt for its intelligence value could anyone decide whether it deserved to be distributed.

In the period before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the material was handled awkwardly and inefficiently, and was distributed even more awkwardly. Nevertheless, the extraordinary experience of reading a foreign government's most closely held communications, sometimes even before the intended recipient, was astonishing. It was so astonishing, someone (possibly President Roosevelt) called it magic. The name stuck.

Other Japanese Ciphers

PURPLE was an enticing, but quite tactically limited, window into Japanese planning and policy because of the peculiar nature of Japanese policy making prior to the War. Early on, a better tactical window was the Japanese Fleet Code (an encoded cypher), called JN-25 by U.S. Navy cryptanalysts. Breaking into the version in use in the months after December 7, 1941 provided enough information to lead to U.S. naval victories in the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, stopping the initial Japanese advances to the south and eliminating the bulk of Japanese naval air power. Later, broken JN-25 traffic also provided the schedule and routing of the plane Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto would be flying in during an inspection tour in the southwest Pacific, giving USAAF pilots a chance to ambush the officer who had conceived the Pearl Harbor attack. And still later, access to Japanese Army messages from decrypts of Army communications traffic assisted in planning the island hopping campaign to the Philippines and beyond.

Another source of information was the Japanese Military Attaché code (known as JMA to the Allies) introduced in 1941. This was a fractionating transposition system based on two-letter code groups which stood for common words and phrases. The groups were written in a square grid according to an irregular pattern and read off vertically, similar to a disrupted columnar transposition. Then the letters were superenciphered using a pre-arranged table of alphabets. This system was broken by John Tiltman at Bletchley Park (England) in 1942.

How Secret Was Magic?

Public notice had actually been served that Japanese cryptography was dangerously inadequate by the Chicago Tribune, which published a series of stories just after Midway, starting on 7 June 1942, which claimed (correctly) that victory was due in large part to the U.S. breaking into Japanese crypto systems (in this case, the JN-25 cypher, though which system(s) had been broken was not mentioned in the newspaper stories). The Tribune claimed the story was written by Stanley Johnston from his own knowledge (and Jane's), but Ronald Lewin points out that the story repeats the layout and errors of a signal from Admiral Nimitz which Johnston saw while on the transport Barnett. Nimitz was reprimanded by Admiral King for sending the dispatch to Task Force commanders on a channel available to nearly all ships. The Lexington's executive officer, Commander Morton T. Seligman was assigned to shore duty and retired early.

However, neither the Japanese nor anyone who might have told them seem to have noticed either the Tribune coverage, or the stories based on the Tribune account published in other U.S. papers. Nor did they notice announcements made on the floor of the United States Congress to the same effect. There were no changes in Japanese cryptography connected with those newspaper accounts or Congressional disclosures.

Alvin Kernan was an aviation ordnanceman on board the aircraft carriers Enterprise and the Hornet during the war. During that time, he was awarded the Navy Cross. In his book, Crossing the Line, he states that when the carrier returned to Pearl Harbor to resupply before the Battle of Midway, the crew knew that the Japanese code had been broken and that U.S. naval forces were preparing to engage the Japanese fleet at Midway. He insists that he "...exactly remembers the occasion on which I was told, with full details about ships and dates..." despite the later insistence that the breaking of the code was kept secret.

U.S. Navy Commander I.J. Galantin, who retired as an Admiral, refers several times to Magic in his 1988 book about his Pacific theater war patrols as captain of the U.S. submarine Halibut. However, Galantin refers to Magic as "Ultra" which was actually the name given to the breaking of the German code. Upon receiving one message from Pacific Fleet command, directing him off normal station to intercept Japanese vessels due to a Magic message, Galantin writes. "I had written my night orders carefully. I made no reference to Ultra and stressed only the need to be very alert for targets in this fruitful area." Galantin had previously mentioned in his book that all submarine captains were aware of "Ultra" (Magic).

In addition, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall discovered early in the war that Magic documents were being widely read at the White House, and that "...at one time over 500 people were reading messages we had intercepted from the Japanese.... Everyone seemed to be reading them".

Source: Wikipedia

The Code Breakers That Halted The Japanese Invasion

Video [50:55]

Shortly after 1:30 am on the 7th of December 1941, the Naval Intercept Station at Bainbridge Island Washington, intercepted a message from Tokyo, bound for the Japanese embassy in Washington DC. The message was in purple, the most secret and complex of the Japanese diplomatic cyphers. As tensions mounted in the pacific, the importance of breaking the enigmatic cypher became all the more pressing. It would become one of the most infamous messages in history.