The Pacific War

Overview

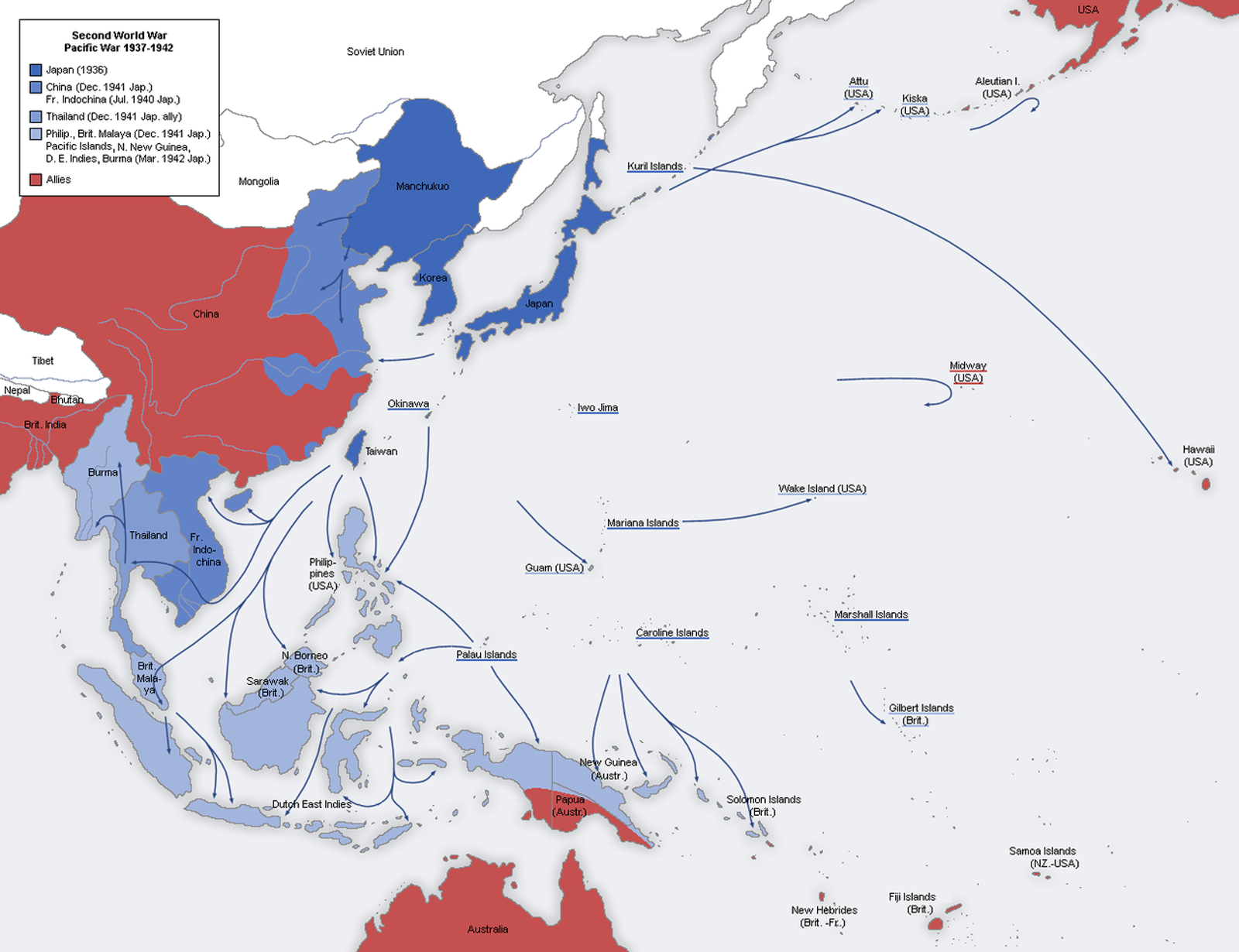

The Pacific War was the theater of World War II that was fought in the Pacific and Asia. It was fought over a vast area that included the Pacific Ocean and islands, the South West Pacific, South-East Asia, and in China (including the 1945 Soviet–Japanese conflict).

The Second Sino-Japanese War between the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China had been in progress since 7 July 1937, with hostilities dating back as far as 19 September 1931 with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. However, it is more widely accepted that the Pacific War itself began on 7/8 December 1941, when Japan invaded Thailand and attacked the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong as well as the United States military and naval bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines.

The Pacific War saw the Allies pitted against Japan and culminated in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Other large aerial bomb attacks by the Allies, accompanied by the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria on 9 August 1945, resulting in the Japanese announcement of intent to surrender on 15 August 1945. The formal surrender of Japan ceremony took place aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945.

After the war, Japan lost all rights and titles to its former possessions in Asia and the Pacific, and its sovereignty was limited to the four main home islands. Japan's Shinto Emperor was forced to relinquish much of his authority and his divine status through the Shinto Directive in order to pave the way for extensive cultural and political reforms.

Theaters

Between 1942 and 1945, there were four main areas of conflict in the Pacific War: China, the Central Pacific, South-East Asia and the South West Pacific. US sources refer to two theaters within the Pacific War: the Pacific theater and the China Burma India Theater (CBI). However these were not operational commands.

In the Pacific, the Allies divided operational control of their forces between two supreme commands, known as Pacific Ocean Areas [Nimitz] and Southwest Pacific Area [MacArthur]. In 1945, for a brief period just before the Japanese surrender, the Soviet Union and its Mongolian ally engaged Japanese forces in Manchuria and northeast China.

The Imperial Japanese Navy did not integrate its units into permanent theater commands. The Imperial Japanese Army, which had already created the Kwantung Army to oversee its occupation of Manchukuo and the China Expeditionary Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War, created the Southern Expeditionary Army Group at the outset of its conquests of South East Asia. This headquarters controlled the bulk of the Japanese Army formations which opposed the Western Allies in the Pacific and South East Asia.

South West Pacific Theater

The South West Pacific theatre, during World War II, was a major theatre of the war between the Allies and the Empire of Japan. It included the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies (except for Sumatra), Borneo, Australia and its mandate Territory of New Guinea (including the Bismarck Archipelago) and the western part of the Solomon Islands. This area was defined by the Allied powers' South West Pacific Area (SWPA) command.

In the South West Pacific theatre, Japanese forces fought primarily against the forces of the United States and Australia. New Zealand, the Netherlands (mainly the Dutch East Indies), the Philippines, United Kingdom, and other Allied nations also contributed forces.

The South Pacific became a major theatre of the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Initially, US warplans called for a counteroffensive across the Central Pacific, but this was disrupted by the loss of battleships at Pearl Harbor. During the First South Pacific Campaign, US forces sought to establish a defensive perimeter against additional Japanese attacks. This was followed by the Second South Pacific Campaign, which began with the Battle of Guadalcanal.

The U.S. General Douglas MacArthur had been in command of the American forces in the Philippines in what was to become the South West Pacific theatre, but was then part of a larger theatre that encompassed the South West Pacific, the Southeast Asian mainland (including Indochina and Malaya) and the North of Australia, under the short lived American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM). Shortly after the collapse of ABDACOM, supreme command of the South West Pacific theatre passed to MacArthur who was appointed Supreme Allied Commander South West Pacific Area on 30 March 1942.

Pacific Ocean Theater

The Pacific Ocean theater, during World War II, was a major theater of the war between the Allies and the Empire of Japan. This area was defined by the Allied powers' Pacific Ocean Area command, which included most of the Pacific Ocean and its islands. Mainland Asia was excluded, as were the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Borneo, Australia, most of the Territory of New Guinea and the western part of the Solomon Islands.

It officially came into existence on March 30, 1942, when US Admiral Chester Nimitz was appointed Supreme Allied Commander Pacific Ocean Areas. In the other major theater in the Pacific region, known as the South West Pacific theatre, Allied forces were commanded by US General Douglas MacArthur. Both Nimitz and MacArthur were overseen by the US Joint Chiefs and the Western Allies Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCoS).

Tensions between Japan and the West

From as early as 1935 Japanese military strategists had concluded the Dutch East Indies were, because of their oil reserves, of considerable importance to Japan. By 1940 they had expanded this to include Indochina, Malaya, and the Philippines within their concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japanese troop build ups in Hainan, Taiwan, and Haiphong were noted, Imperial Japanese Army officers were openly talking about an inevitable war, and Admiral Sankichi Takahashi was reported as saying a showdown with the United States was necessary.

In an effort to discourage Japanese militarism, Western powers including Australia, the United States, Britain, and the Dutch government in exile, which controlled the petroleum-rich Dutch East Indies, stopped selling oil, iron ore, and steel to Japan, denying it the raw materials needed to continue its activities in China and French Indochina. In Japan, the government and nationalists viewed these embargos as acts of aggression; imported oil made up about 80% of domestic consumption, without which Japan's economy, let alone its military, would grind to a halt. The Japanese media, influenced by military propagandists, began to refer to the embargoes as the "ABCD ("American-British-Chinese-Dutch") encirclement" or "ABCD line".

Faced with a choice between economic collapse and withdrawal from its recent conquests (with its attendant loss of face), the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (GHQ) began planning for a war with the Western powers in April or May 1941.

Japanese Preparations

Japan's key objective during the initial part of the conflict was to seize economic resources in the Dutch East Indies and Malaya which offered Japan a way to escape the effects of the Allied embargo. This was known as the Southern Plan. It was also decided—because of the close relationship between the United Kingdom and United States, and the belief the US would inevitably become involved—Japan would also require taking the Philippines, Wake and Guam.

Japanese planning was for fighting a limited war where Japan would seize key objectives and then establish a defensive perimeter to defeat Allied counterattacks, which in turn would lead to a negotiated peace. The attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with carrier-based aircraft of the Combined Fleet was to give the Japanese time to complete a perimeter.

The early period of the war was divided into two operational phases. The First Operational Phase was further divided into three separate parts in which the major objectives of the Philippines, British Malaya, Borneo, Burma, Rabaul and the Dutch East Indies would be occupied. The Second Operational Phase called for further expansion into the South Pacific by seizing eastern New Guinea, New Britain, Fiji, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area. In the Central Pacific, Midway was targeted as were the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific. Seizure of these key areas would provide defensive depth and deny the Allies staging areas from which to mount a counteroffensive.

By November these plans were essentially complete, and were modified only slightly over the next month. Japanese military planners' expectation of success rested on the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union being unable to effectively respond to a Japanese attack because of the threat posed to each by Germany; the Soviet Union was even seen as unlikely to commence hostilities.

The Japanese leadership was aware that a total military victory in a traditional sense against the US was impossible; the alternative would be negotiating for peace after their initial victories, which would recognize Japanese hegemony in Asia. In fact, the Imperial GHQ noted, should acceptable negotiations be reached with the Americans, the attacks were to be canceled—even if the order to attack had already been given. The Japanese leadership looked to base the conduct of the war against America on the historical experiences of the successful wars against China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–05), in both of which a strong continental power was defeated by reaching limited military objectives, not by total conquest.

They also planned, should the United States transfer its Pacific Fleet to the Philippines, to intercept and attack this fleet en route with the Combined Fleet, in keeping with all Japanese Navy prewar planning and doctrine. If the United States or Britain attacked first, the plans further stipulated the military were to hold their positions and wait for orders from GHQ. The planners noted attacking the Philippines and British Malaya still had possibilities of success, even in the worst case of a combined preemptive attack including Soviet forces.

Japanese offensives, 1941–42

Following prolonged tensions between Japan and the Western powers, units of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army launched simultaneous surprise attacks on Australian, British, Dutch and US forces on 7 December (8 December in Asia/West Pacific time zones).

The locations of this first wave of Japanese attacks included: Hawaii, Malaya, the Kingdom of Sarawak, Guam, Wake Island, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. Japanese forces also simultaneously invaded southern and eastern Thailand and were resisted for several hours, before the Thai government signed an armistice with Japan.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

In the early hours of 7 December (Hawaiian time), Japan launched a major surprise carrier-based air strike on Pearl Harbor without explicit warning, which crippled the US Pacific Fleet, leaving eight American battleships out of action, American aircraft destroyed, and 2,403 American citizens dead. At the time of the attack, the US was not officially at war anywhere in the world as the Japanese embassy failed to decipher and deliver the Japanese ultimatum to the American government before noon December 7 (Washington time), which means that the people killed or property destroyed at Pearl Harbor by the Japanese attack had a non-combatant status. The Japanese had gambled that the United States, when faced with such a sudden and massive blow, would agree to a negotiated settlement and allow Japan free rein in Asia. This gamble did not pay off. American losses were less serious than initially thought: the American aircraft carriers, which would prove to be more important than battleships, were at sea, and vital naval infrastructure (fuel oil tanks, shipyard facilities, and a power station), submarine base, and signals intelligence units were unscathed. Japan's fallback strategy, relying on a war of attrition to make the US come to terms, was beyond the IJN's capabilities.

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 800,000-member America First Committee vehemently opposed any American intervention in the European conflict, even as America sold military aid to Britain and the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program. Opposition to war in the US vanished after the attack. On 8 December, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Netherlands declared war on Japan, followed by China and Australia the next day. Four days after Pearl Harbor, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, drawing the country into a two-theater war. This is widely agreed to be a grand strategic blunder, as it abrogated both the benefit Germany gained by Japan's distraction of the US and the reduction in aid to Britain, which both Congress and Hitler had managed to avoid during over a year of mutual provocation, which would otherwise have resulted.

Threat to Australia

In late 1941, as the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor, most of Australia's best forces were committed to the fight against Hitler in the Mediterranean Theatre. Australia was ill-prepared for an attack, lacking armaments, modern fighter aircraft, heavy bombers, and aircraft carriers. While still calling for reinforcements from Churchill, the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin called for American support with a historic announcement on 27 December 1941:

"The Australian Government ... regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies' fighting plan. Without inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."

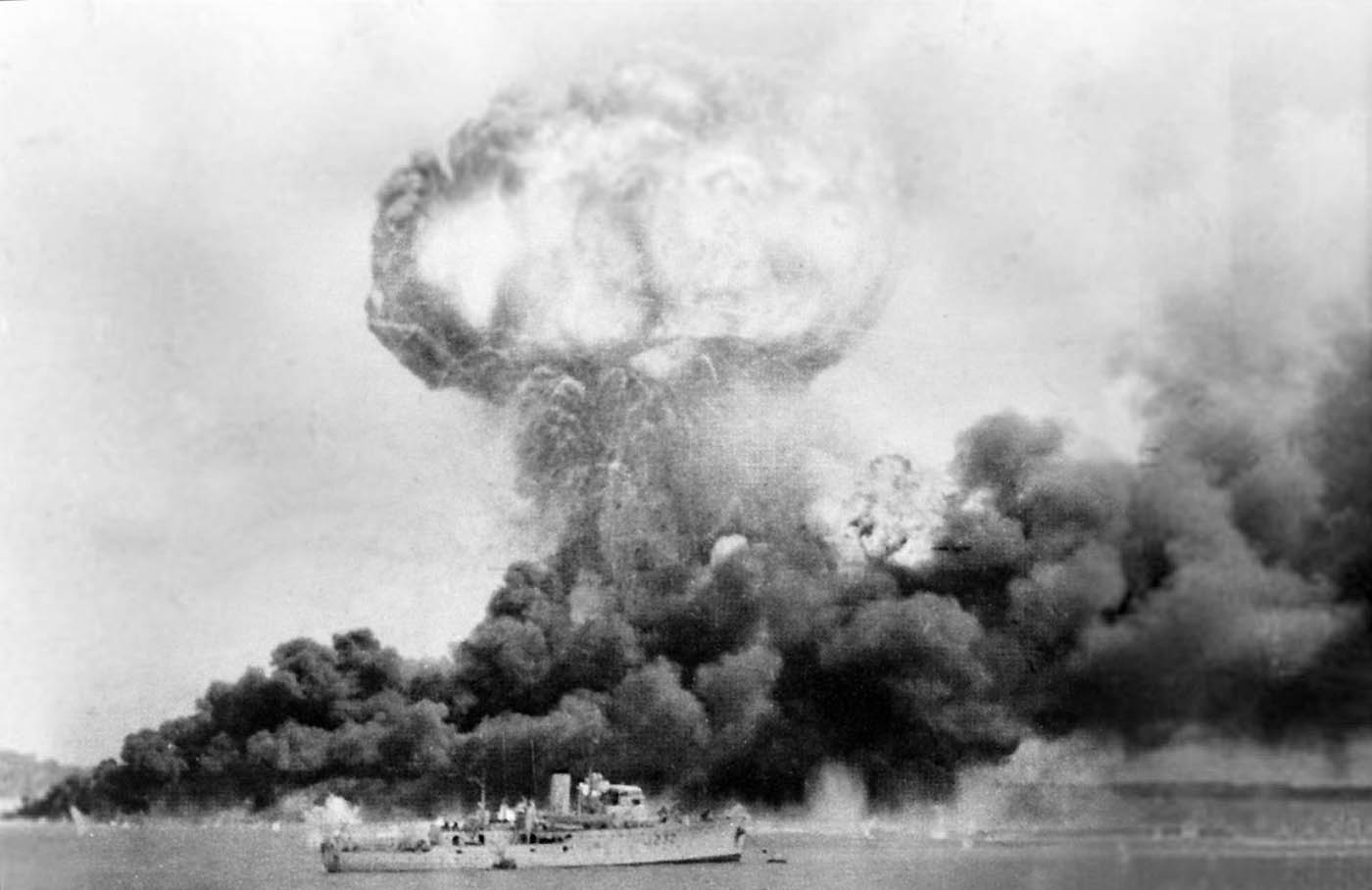

Australia had been shocked by the speedy collapse of British Malaya and Fall of Singapore in which around 15,000 Australian soldiers became prisoners of war. Curtin predicted the "battle for Australia" would now follow. The Japanese established a major base in the Australian Territory of New Guinea in early 1942. On 19 February, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid, the first time the Australian mainland had been attacked. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times.

Two battle-hardened Australian divisions were steaming from the Mid-East for Singapore. Churchill wanted them diverted to Burma, but Curtin insisted on a return to Australia. In early 1942 elements of the Imperial Japanese Navy proposed an invasion of Australia. The Imperial Japanese Army opposed the plan and it was rejected in favor of a policy of isolating Australia from the United States via blockade by advancing through the South Pacific. The Japanese decided upon a seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, capital of the Australian Territory of Papua which would put Northern Australia within range of Japanese bomber aircraft.

Allies Re-Group, 1942–43

President Franklin Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines to formulate a Pacific defense plan with Australia in March 1942. Curtin agreed to place Australian forces under the command of MacArthur who became Supreme Commander, South West Pacific. MacArthur moved his headquarters to Melbourne in March 1942 and American troops began massing in Australia. Enemy naval activity reached Sydney in late May 1942, when Japanese midget submarines launched a daring raid on Sydney Harbor. On 8 June 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and the city of Newcastle.

Japanese Strategy and the Doolittle Raid

Having accomplished their objectives during the First Operation Phase with ease, the Japanese now turned to the second. The Second Operational Phase planned to expand Japan's strategic depth by adding eastern New Guinea, New Britain, the Aleutians, Midway, the Fiji Islands, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area. However, the Naval General Staff, the Combined Fleet, and the Imperial Army, all had different strategies on the next sequence of operations. The Naval General Staff advocated an advance to the south to seize parts of Australia. However, with large numbers of troops still engaged in China combined with those stationed in Manchuria facing the Soviet Union, the Imperial Japanese Army declined to contribute the forces necessary for such an operation, this quickly led to the abandonment of the concept.

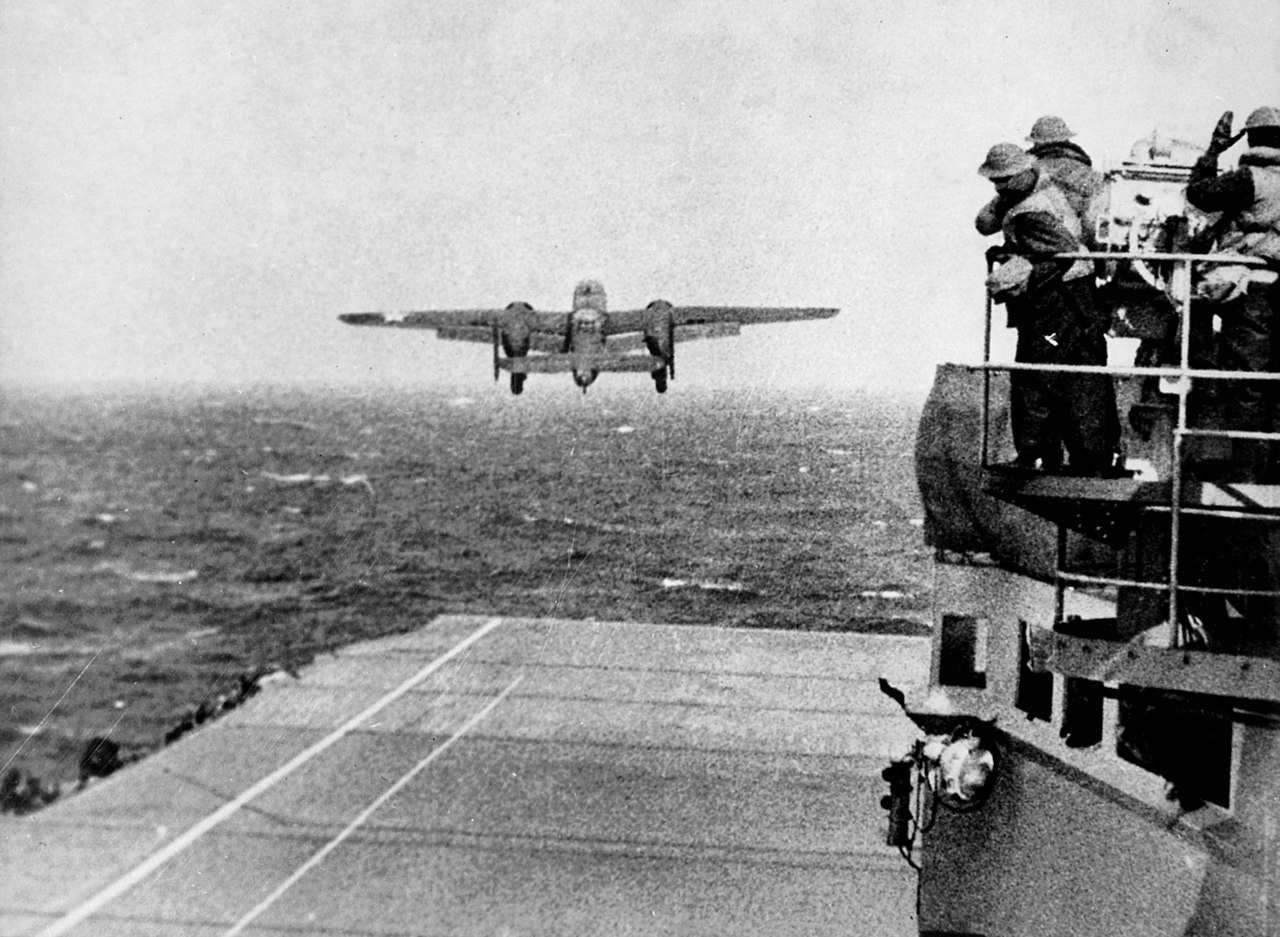

The Naval General Staff still wanted to cut the sea links between Australia and the United States by capturing New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. Since this required far fewer troops, on March 13 the Naval General Staff and the Army agreed to operations with the goal of capturing Fiji and Samoa. The Second Operational Phase began well when Lae and Salamaua, located in eastern New Guinea, were captured on March 8. However, on March 10, American carrier aircraft attacked the invasion forces and inflicted considerable losses. The raid had major operational implications since it forced the Japanese to stop their advance in the South Pacific, until the Combined Fleet provided the means to protect future operations from American carrier attack. Concurrently, the Doolittle Raid occurred in April 1942, where 16 bombers took off from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, 600 miles (970 km) from Japan. The raid inflicted minimal material damage on Japanese soil but was a huge morale boost for the United States, it also had major psychological repercussions in Japan, in exposing the vulnerabilities of the Japanese homeland. As the raid was mounted by a carrier task force, it consequently highlighted to the dangers the Japanese home islands could face until the destruction of the American carrier forces was achieved. With only Marcus Island and a line of converted trawlers patrolling the vast waters that separate Wake and Kamchatka, the Japanese east coast was left open to attack.

Admiral Yamamoto now perceived that was it was essential to complete the destruction of the United States Navy, which had begun at Pearl Harbor. His proposal to achieve this was by attacking and occupying Midway Atoll an objective, which he assessed, the Americans would be certain to fight for as they would be forced to contest a Japanese invasion there since it was close enough to Hawaii. During a series of meetings held from April 2–5, between the Naval General Staff and representatives of the Combined Fleet reached a compromise. Yamamoto got his Midway operation, but only after he had threatened to resign. In return, however, Yamamoto had to agree to two demands from the Naval General Staff both of which had implications for the Midway operation. In order to cover the offensive in the South Pacific, Yamamoto agreed to allocate one carrier division to the operation against Port Moresby. Yamamoto also agreed to include an attack to seize strategic points in the Aleutian Islands simultaneously with the Midway operation, these were enough to remove the Japanese margin of superiority in the coming Midway attack.

Coral Sea

The attack on Port Moresby was codenamed the MO Operation and was divided into several parts or phases. In the first, Tulagi would be occupied on May 3, the carriers would then conduct a wide sweep through the Coral Sea to find and attack and destroy Allied naval forces, with the landings conducted to capture Port Moresby scheduled for May 10.[100] The MO Operation featured a force of 60 ships led by the two carriers: Shōkaku and Zuikaku, one light carrier (Shōhō), six heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and 15 destroyers. Additionally, some 250 aircraft were assigned to the operation including 140 aboard the three carriers. However, the actual battle did not go according to plan, although Tulagi was seized on May 3, the following day, aircraft from the American carrier Yorktown struck the invasion force. The element of surprise, which had been present at Pearl Harbor, was now lost due to the success of Allied codebreakers who had discovered the attack would be against Port Moresby. From the Allied point of view if Port Moresby fell, the Japanese would control the seas to the north and west of Australia and could isolate the country.

An Allied task force under the command of Admiral Fletcher, with the carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown was assembled to stop the Japanese advance. For the next two days, both the American and Japanese carrier forces tried unsuccessfully to locate each other. On May 7, the Japanese carriers launched a full strike on a contact reported to be enemy carriers, the report though turned out to be false. The strike force found and struck only an oiler, the Neosho and the destroyer Sims. The American carriers also launched a strike with incomplete reconnaissance, instead of finding the main Japanese carrier force, they only located and sank the Shōhō. On May 8, the opposing carrier forces finally found each other and exchanged air strikes. The 69 aircraft from the two Japanese carriers succeeded in sinking the carrier Lexington and damaging Yorktown, in return the Americans damaged the Shōkaku. Although Zuikaku was the left undamaged, aircraft and personnel losses to Zuikaku were heavy and the Japanese were unable to support a landing on Port Moresby. As a result, the MO Operation was cancelled, and the Japanese were subsequently forced to abandon their attempts to isolate Australia.

Although they managed to sink a carrier, the battle was a disaster for the Japanese. Not only was the attack on Port Moresby halted, which constituted the first strategic Japanese setback of the war, but all three carriers that were committed to the battle would now be unavailable for the operation against Midway. The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first naval battle fought in which ships involved never sighted each other, with attacks solely by aircraft.

After Coral Sea, the Japanese had four fleet carriers operational—Sōryū, Kaga, Akagi and Hiryū—and believed that the Americans had a maximum of two—Enterprise and Hornet. Saratoga was out of action, undergoing repair after a torpedo attack, while Yorktown had been damaged at Coral Sea and was believed by Japanese naval intelligence to have been sunk. She would, in fact, sortie for Midway after just three days' of repairs to her flight deck, with civilian work crews still aboard, in time to be present for the next decisive engagement.

Midway

Admiral Yamamoto viewed the operation against Midway as the potentially decisive battle of the war which could lead to the destruction of American strategic power in the Pacific, and subsequently open the door for a negotiated peace settlement with the United States, favorable to Japan. For the operation, the Japanese had only four carriers; Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū and Hiryū. Through strategic and tactical surprise, the Japanese would knock out Midway's air strength and soften it for a landing by 5,000 troops. After the quick capture of the island, the Combined Fleet would lay the basis for the most important part of the operation. Yamamoto hoped that the attack would lure the Americans into a trap. Midway was to be bait for the USN which would depart Pearl Harbor to counterattack after Midway had been captured. When the Americans arrived, he would concentrate his scattered forces to defeat them. An important aspect of the scheme was Operation AL, which was the plan to seize two islands in the Aleutians, concurrently with the attack on Midway. Contradictory to persistent myth, the Aleutian operation was not a diversion to draw American forces from Midway, as the Japanese wanted the Americans to be drawn to Midway, rather than away from it. However, in May, Allied codebreakers discovered the planned attack on Midway. Yamamoto's complex plan had no provision for intervention by the American fleet before the Japanese had expected them. Planned surveillance of the American fleet in Pearl Harbor by long-ranged seaplane did not happen as a result of an abortive identical operation in March. Planned detection of the American departure by submarine patrol line faltered on their late departure, a product of Nagumo's hasty sortie.

The battle began on June 3, when American aircraft from Midway spotted and attacked the Japanese transport group 700 miles (1,100 km) west of the atoll. On June 4, the Japanese launched a 108-aircraft strike on the island, the attackers brushing aside Midway's defending fighters but failing to deliver a decisive blow to the island's facilities. Most importantly, the strike aircraft based on Midway had already departed to attack the Japanese carriers, which had been spotted. This information was passed to the three American carriers and a total of 116 carrier aircraft, in addition to those from Midway, were on their way to attack the Japanese. The aircraft from Midway attacked, but failed to score a single hit on the Japanese. In the middle of these uncoordinated attacks, a Japanese scout aircraft reported the presence of an American task force, but it was not until later that the presence of an American carrier was confirmed.

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, was put in a difficult tactical situation in which he had to counter continuous American air attacks and prepare to recover his Midway strike, while deciding whether to mount an immediate strike on the American carrier or wait to prepare a proper attack. After quick deliberation, he opted for a delayed but better-prepared attack on the American task force after recovering his Midway strike and properly arming aircraft. However, beginning at 10.22am, American SBD Dauntlesses surprised and successfully attacked three of the Japanese carriers. With their decks laden with fully fueled and armed aircraft, Sōryū, Kaga, and Akagi were turned into blazing wrecks. A Japanese single carrier, Hiryū, remained operational, and launched an immediate counterattack. Both of her attacks hit Yorktown and put her out of action. Later in the afternoon, aircraft from the two remaining American carriers found and destroyed Hiryū. The crippled Yorktown, along with the destroyer Hammann, were both sunk by the Japanese submarine I-168. With the striking power of the Kido Butai having been destroyed, Japan's offensive power was blunted. Early on the morning of June 5, with the battle lost, the Japanese cancelled the Midway operation and the initiative in the Pacific was in the balance. Although losing four carriers, Parshall and Tully note losses at Midway did not radically degrade the fighting capabilities of Japanese naval aviation as a whole.

New Guinea and the Solomons

Japanese land forces continued to advance in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. From July 1942, a few Australian reserve battalions, many of them very young and untrained, fought a stubborn rearguard action in New Guinea, against a Japanese advance along the Kokoda Track, towards Port Moresby, over the rugged Owen Stanley Ranges. The militia, worn out and severely depleted by casualties, were relieved in late August by regular troops from the Second Australian Imperial Force, returning from action in the Mediterranean theater. In early September 1942 Japanese marines attacked a strategic Royal Australian Air Force base at Milne Bay, near the eastern tip of New Guinea. They were beaten back by Allied (primarily Australian Army) forces.

By late 1942, Japanese headquarters decided to make Guadalcanal their priority. They ordered the Japanese on the Kokoda Track, within sight of the lights of Port Moresby, to retreat to the northeastern coast of New Guinea. Australian and US forces attacked their fortified positions and after more than two months of fighting in the Buna–Gona area finally captured the key Japanese beachhead in early 1943.

In June 1943, the Allies launched Operation Cartwheel, which defined their offensive strategy in the South Pacific. The operation was aimed at isolating the major Japanese forward base at Rabaul and cutting its supply and communication lines. This prepared the way for Nimitz's island-hopping campaign towards Japan.

Guadalcanal

At the same time as major battles raged in New Guinea, Allied forces became aware of a Japanese airfield under construction at Guadalcanal through coastwatchers. On 7 August 1943, US Marines landed on the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Solomons. Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, commander of the newly formed Eighth Fleet at Rabaul, reacted quickly. Gathering five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer, sailed to engage the Allied force off the coast of Guadalcanal. On the night of August 8–9, 1943, Mikawa's quick response resulted in a brilliant victory during which four Allied heavy cruisers were sunk in the Battle of Savo Island. No Japanese ships were lost, it was one of the worst Allied naval defeats of the war. The battle was colloquially known among Allied Guadalcanal veterans as "The Battle of the Five Sitting Ducks."

The victory was only mitigated by the failure of the Japanese to attack the vulnerable transports. Had it been done so, the first American counterattack in the Pacific could have been stopped. The Japanese originally perceived the American landings as nothing more than a reconnaissance in force.

With Japanese and Allied forces occupying various parts of the island, over the following six months both sides poured resources into an escalating battle of attrition on land, at sea, and in the sky. Most of the Japanese aircraft based in the South Pacific were redeployed to the defense of Guadalcanal. Many were lost in numerous engagements with the Allied air forces based at Henderson Field as well as carrier based aircraft. Meanwhile, Japanese ground forces launched repeated attacks on heavily defended US positions around Henderson Field, in which they suffered appalling casualties. To sustain these offensives, resupply was carried out by Japanese convoys, termed the "Tokyo Express" by the Allies. The convoys often faced night battles with enemy naval forces in which they expended destroyers that the IJN could ill-afford to lose. Later fleet battles involving heavier ships and even daytime carrier battles resulted in a stretch of water near Guadalcanal becoming known as "Ironbottom Sound" from the multitude of ships sunk on both sides. However, the Allies were much better able to replace these losses. Finally recognizing that the campaign to recapture Henderson Field and secure Guadalcanal had simply become too costly to continue, the Japanese evacuated the island and withdrew in February 1943. In the six-month war of attrition, the Japanese had lost Guadalcanal as a result of failing to commit enough forces in sufficient time.

Allied offensives, 1943–44

Midway proved to be the last great naval battle for two years. The United States used the ensuing period to turn its vast industrial potential into increased numbers of ships, planes, and trained aircrew. At the same time, Japan, lacking an adequate industrial base or technological strategy, a good aircrew training program, or adequate naval resources and commerce defense, fell further and further behind. In strategic terms the Allies began a long movement across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like Truk, Rabaul, and Formosa, were neutralized by air attack and bypassed. The goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks, improve the submarine blockade, and finally (only if necessary) execute an invasion.

In November 1943 US Marines sustained high casualties when they overwhelmed the 4,500-strong garrison at Tarawa. This helped the Allies to improve the techniques of amphibious landings, learning from their mistakes and implementing changes such as thorough pre-emptive bombings and bombardment, more careful planning regarding tides and landing craft schedules, and better overall coordination.

The US Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest (and as Japan hoped); the Allied advance could only be stopped by a Japanese naval attack, which oil shortages (induced by submarine attack) made impossible.

Submarine Warfare

US submarines, as well as some British and Dutch vessels, operating from bases at Cavite in the Philippines (1941–42); Fremantle and Brisbane, Australia; Pearl Harbor; Trincomalee, Ceylon; Midway; and later Guam, played a major role in defeating Japan, even though submarines made up a small proportion of the Allied navies—less than two percent in the case of the US Navy. Submarines strangled Japan by sinking its merchant fleet, intercepting many troop transports, and cutting off nearly all the oil imports essential to weapons production and military operations. By early 1945, Japanese oil supplies were so limited that its fleet was virtually stranded.

The Japanese military claimed its defenses sank 468 Allied submarines during the war. In reality, only 42 American submarines were sunk in the Pacific due to hostile action, with 10 others lost in accidents or as the result of friendly fire. The Dutch lost five submarines due to Japanese attack or minefields, and the British lost three.

American submarines accounted for 56% of the Japanese merchantmen sunk; mines or aircraft destroyed most of the rest. American submariners also claimed 28% of Japanese warships destroyed. Furthermore, they played important reconnaissance roles, as at the battles of the Philippine Sea (June 1944) and Leyte Gulf (October 1944) (and, coincidentally, at Midway in June 1942), when they gave accurate and timely warning of the approach of the Japanese fleet. Submarines also rescued hundreds of downed fliers, including future US president George H. W. Bush.

Allied submarines did not adopt a defensive posture and wait for the enemy to attack. Within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, in retribution against Japan, Roosevelt promulgated a new doctrine: unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. This meant sinking any warship, commercial vessel, or passenger ship in Axis-controlled waters, without warning and without aiding survivors. At the outbreak of the war in the Pacific, the Dutch admiral in charge of the naval defense of the East Indies, Conrad Helfrich, gave instructions to wage war aggressively. His small force of submarines sank more Japanese ships in the first weeks of the war than the entire British and US navies together, an exploit which earned him the nickname "Ship-a-day Helfrich".

While Japan had a large number of submarines, they did not make a significant impact on the war. In 1942, the Japanese fleet submarines performed well, knocking out or damaging many Allied warships. However, Imperial Japanese Navy (and pre-war US) doctrine stipulated that only fleet battles, not commerce raiding could win naval campaigns. So, while the US had an unusually long supply line between its west coast and frontline areas, leaving it vulnerable to submarine attack, Japan used its submarines primarily for long-range reconnaissance and only occasionally attacked US supply lines. The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia in 1942 and 1943 also achieved little.

As the war turned against Japan, IJN submarines increasingly served to resupply strongholds which had been cut off, such as Truk and Rabaul. In addition, Japan honored its neutrality treaty with the Soviet Union and ignored American freighters shipping millions of tons of military supplies from San Francisco to Vladivostok, much to the consternation of its German ally.

The US Navy, by contrast, relied on commerce raiding from the outset. However, the problem of Allied forces surrounded in the Philippines, during the early part of 1942, led to diversion of boats to "guerrilla submarine" missions. Basing in Australia placed boats under Japanese aerial threat while en route to patrol areas, reducing their effectiveness, and Nimitz relied on submarines for close surveillance of enemy bases. Furthermore, the standard-issue Mark 14 torpedo and its Mark VI exploder both proved defective, problems which were not corrected until September 1943. Worst of all, before the war, an uninformed US Customs officer had seized a copy of the Japanese merchant marine code (called the "maru code" in the USN), not knowing that the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) had broken it. The Japanese promptly changed it, and the new code was not broken again by OP-20-G until 1943.

Thus, only in 1944 did the US Navy begin to use its 150 submarines to maximum effect: installing effective shipboard radar, replacing commanders deemed lacking in aggression, and fixing the faults in the torpedoes. Japanese commerce protection was "shiftless beyond description," and convoys were poorly organized and defended compared to Allied ones, a product of flawed IJN doctrine and training – errors concealed by American faults as much as Japanese overconfidence. The number of American submarines patrols (and sinkings) rose steeply: 350 patrols (180 ships sunk) in 1942, 350 (335) in 1943, and 520 (603) in 1944. By 1945, sinkings of Japanese vessels had decreased because so few targets dared to venture out on the high seas. In all, Allied submarines destroyed 1,200 merchant ships – about five million tons of shipping. Most were small cargo carriers, but 124 were tankers bringing desperately needed oil from the East Indies. Another 320 were passenger ships and troop transports. At critical stages of the Guadalcanal, Saipan, and Leyte campaigns, thousands of Japanese troops were killed or diverted from where they were needed. Over 200 warships were sunk, ranging from many auxiliaries and destroyers to one battleship and no fewer than eight carriers.

Underwater warfare was especially dangerous; of the 16,000 Americans who went out on patrol, 3,500 (22%) never returned, the highest casualty rate of any American force in World War II. The Joint Army–Navy Assessment Committee assessed US submarine credits. The Japanese losses, 130 submarines in all, were higher.

Beginning of the end in the Pacific, 1944

In May 1943, the Japanese prepared Operation Z or the Z Plan, which envisioned the use of Japanese naval power to counter American forces threatening the outer defense perimeter line. This line extended from the Aleutians down through Wake, the Marshall and Gilbert Islands, Nauru, the Bismarck Archipelago, New Guinea, then westward past Java and Sumatra to Burma. In 1943-44, Allied forces in the Solomons began driving relentlessly to Rabaul, eventually encircling and neutralizing the stronghold. With their position in the Solomons disintegrating, the Japanese modified the Z Plan by eliminating the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, and the Bismarck Archipelago as vital areas to be defended. They then based their possible actions on the defense of an inner perimeter, which included the Marianas, Palau, Western New Guinea, and the Dutch East Indies. Meanwhile, in the Central Pacific the Americans initiated a major offensive, beginning in November 1943 with landings in the Gilbert Islands. The Japanese were forced to watch helplessly as their garrisons in the Gilberts and then the Marshalls were crushed. The strategy of holding overextended island garrisons was fully exposed.

In February 1944, the US Navy's fast carrier task force, during Operation Hailstone, attacked the major naval base of Truk. Although the Japanese had moved their major vessels out in time to avoid being caught at anchor in the atoll, two days of air attacks resulted in significant losses to Japanese aircraft and merchant shipping. The Japanese were forced to abandon Truk and were now unable to counter the Americans on any front on the perimeter. Consequently, the Japanese retained their remaining strength in preparation for what they hoped would be a decisive battle. The Japanese then developed a new plan, known as A-GO. A-GO envisioned a decisive fleet action that would be fought somewhere from the Palaus to the Western Carolines. It was in this area that the newly formed Mobile Fleet along with large numbers of land-based aircraft, would be concentrated. If the Americans attacked the Marianas, they would be attacked by land-based planes in the vicinity. Then the Americans would be lured into the areas where the Mobile Fleet could defeat them.

The Marianas and the Philippine Sea

On 15 June 1944, 535 ships began landing 128,000 US Army and Marine Corps personnel on the island of Saipan in the Northern Marianas. The Allies aimed to establish airfields near enough the Japanese Home Islands, including Honshu, the location of Tokyo, to allow their bombing with the new Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The ability to plan and execute such a complex operation in the space of 90 days was indicative of Allied logistical superiority.

Japanese commanders saw holding Saipan as imperative. The only way to do so involved destroying the U.S. Fifth Fleet, which had 15 fleet carriers and 956 planes, 7 battleships, 28 submarines, and 69 destroyers, as well as several light and heavy cruisers. Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa attacked with nine-tenths of Japan's fighting fleet, which included nine carriers with 473 planes, 5 battleships, several cruisers, and 28 destroyers. Ozawa's pilots were outnumbered 2:1 and their aircraft were becoming or were already obsolete. The Japanese had considerable antiaircraft defenses but lacked proximity fuzes or good radar. With the odds against him, Ozawa devised an appropriate strategy. His planes had greater range because they were not weighed down with protective armor; they could attack at about 480 km (300 mi), and could search a radius of 900 km[citation needed] (560 mi). U.S. Navy Hellcat fighters could attack only within 200 miles (320 km) and search only within a 325-mile (523 km) radius. Ozawa planned to use this advantage by positioning his fleet 300 miles (480 km) out. The Japanese planes would hit the U.S. carriers, land at Guam to refuel, then hit the enemy again when returning to their carriers. Ozawa also counted on about 500 land-based planes at Guam and other islands.

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance had overall command of the U.S. Fifth Fleet. The Japanese plan would have failed if the much larger U.S. fleet had closed on Ozawa and attacked aggressively; Ozawa correctly inferred Spruance would not attack. U.S. Admiral Marc Mitscher, in tactical command of Task Force 58, with its 15 carriers, was aggressive, but Spruance vetoed Mitscher's plan to hunt down Ozawa because Spruance's orders made protecting the landings on Saipan his first priority.

The forces converged in the largest sea-battle of World War II up to that point - the Battle of the Philippine Sea (19–20 June 1944). Over the previous month American destroyers had destroyed 17 of 25 submarines out of Ozawa's screening force. Repeated US raids destroyed the Japanese land-based planes. Ozawa's main attack lacked coordination, with the Japanese planes arriving at their targets in a staggered sequence. Following a directive from Nimitz, the US carriers all had combat-information centers, which interpreted the flow of radar data and radioed interception orders to the Hellcats. The result was later dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. The few attackers to reach the US fleet encountered massive AA fire with proximity fuzes. Only one American warship was slightly damaged.

On the second day, US reconnaissance planes located Ozawa's fleet, 275 miles (443 km) away, and submarines sank two Japanese carriers. Mitscher launched 230 torpedo planes and dive bombers. He then discovered the enemy was actually another 60 miles (97 km) further off, out of aircraft range (based on a roundtrip flight). Mitscher decided this chance to destroy the Japanese fleet was worth the risk of aircraft losses due to running out of fuel on the return flight. Overall, the US lost 130 planes and 76 aircrew; however, Japan lost 450 planes, three carriers, and 445 aircrew. US aircraft had effectively destroyed the Imperial Japanese Navy's carrier force.

A month after the invasion of Saipan, the US recaptured Guam and captured Tinian.

Once captured, the islands of Saipan and Tinian were used extensively by the United States military as they finally put mainland Japan within round-trip range of American B-29 bombers. In response, Japanese forces attacked the bases on Saipan and Tinian from November 1944 to January 1945. At the same time and afterwards, the United States Army Air Forces based out of these islands conducted an intense strategic bombing campaign against the Japanese cities of military and industrial importance, including Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe and others.

Leyte Gulf, 1944

After the disaster at Philippine Sea the Japanese were left with two choices: either to commit their remaining strength in an all-out offensive or to sit by while the Americans occupied the Philippines and cut the sea lanes between Japan and the vital resources from the Dutch East Indies and Malaya. The plan devised by the Japanese was a final attempt to create a decisive battle by utilizing their last remaining strength, which the firepower of its heavy cruisers and battleships, which were to be all committed against the American beachhead at Leyte. The Japanese planned to use their remaining carriers as bait, in order to lure the American carriers away from Leyte Gulf long enough for the heavy warships to enter and destroy any American ships present.

The Japanese assembled a force totaling four carriers, nine battleships, 14 heavy cruisers, seven light cruisers, and 35 destroyers. They would be split into three forces. The "Center Force", under the command of Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, consisted of five battleships (including the Yamato and Musashi), 12 cruisers and 13 destroyers; the "Northern Force", under the command of Jisaburō Ozawa comprised four carriers, two battleships partly converted to carriers, three light cruisers and nine destroyers; the "Southern Force" contained two groups, one under the command of Shōji Nishimura consisting of two Fusō-class battleships, one heavy cruiser and four destroyers, the other under Kiyohide Shima comprised two heavy cruisers, a light cruiser and four destroyers. The main Center Force would pass through the San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea, turn southwards, and then attack the landing area. The two separate groups of the Southern Force would join up and strike at the landing area through the Surigao Strait, while Northern Force with the Japanese carriers was to lure the main American covering forces away from Leyte, the carriers only embarked a total of just 108 aircraft.

However, after departing from Brunei Bay on October 23, the Center Force was attacked by two American submarines which resulted in the loss of two heavy cruisers with another crippled. The next day, after entering the Sibuyan Sea on October 24, Center Force was assaulted by American carrier aircraft throughout the whole day leaving another heavy cruiser being forced to retire. The Americans then targeted the Musashi and sank it under a barrage of torpedo and bomb hits. Many other ships of Center Force were attacked, but continued on. Convinced that their attacks had made Center Force ineffective, the American carriers headed north to address the newly detected threat of the Japanese carriers of Ozawa's Force. On the night of October 24–25, the Southern Force under Nishimura, attempted to enter Leyte Gulf from the south through Surigao Strait where an American-Australian force led by Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf, of six battleships, eight cruisers, and 26 destroyers ambushed the Japanese. Utilizing radar-guided torpedo attacks, American destroyers sank one of the battleships and three destroyers while damaging the other battleship. Radar guided naval gunfire then finished off the second battleship, with only a single Japanese destroyer surviving. As a result of observing radio silence, Shima's group was unable to coordinate and synchronize its movements with Nishimura's group and subsequently arrived at Surigao Strait in the middle of the encounter; after making a haphazard torpedo attack Shima retreated.

Off Cape Engaño, the Americans launched over 500 aircraft sorties at the Northern force, followed up by a surface group of cruisers and destroyers. All four Japanese carriers were sunk, but this part of the Japanese plan succeeded in drawing the American carriers away from Leyte Gulf. On October 25, the final major surface action fought between the Japanese and the American fleets during the war, occurred off Samar, when Center Force fell upon a group of American escort carriers escorted by only destroyers and destroyer escorts. Both sides were surprised, but the outcome looked certain since the Japanese had four battleships, six heavy cruisers, and two light cruisers leading two destroyer squadrons. However, they did not press home their advantage, and were content to conduct a largely indecisive gunnery duel before breaking off. Japanese losses were extremely heavy with four carriers, three battleships, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers and eleven destroyers sunk, while the Americans lost one light carrier and two escort carriers, a destroyer and two destroyer escorts. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was arguably the largest naval battle in history and was the largest naval battle of World War II.

Philippines, 1944–45

On 20 October 1944 the US Sixth Army, supported by naval and air bombardment, landed on the favorable eastern shore of Leyte, north of Mindanao. The US Sixth Army continued its advance from the east, as the Japanese rushed reinforcements to the Ormoc Bay area on the western side of the island. While the Sixth Army was reinforced successfully, the US Fifth Air Force was able to devastate the Japanese attempts to resupply. In torrential rains and over difficult terrain, the advance continued across Leyte and the neighboring island of Samar to the north. On 7 December US Army units landed at Ormoc Bay and, after a major land and air battle, cut off the Japanese ability to reinforce and supply Leyte. Although fierce fighting continued on Leyte for months, the US Army was in control.

On 15 December 1944 landings against minimal resistance were made on the southern beaches of the island of Mindoro, a key location in the planned Lingayen Gulf operations, in support of major landings scheduled on Luzon. On 9 January 1945, on the south shore of Lingayen Gulf on the western coast of Luzon, General Krueger's Sixth Army landed his first units. Almost 175,000 men followed across the twenty-mile (32 km) beachhead within a few days. With heavy air support, Army units pushed inland, taking Clark Field, 40 miles (64 km) northwest of Manila, in the last week of January.

Two more major landings followed, one to cut off the Bataan Peninsula, and another, that included a parachute drop, south of Manila. Pincers closed on the city and, on 3 February 1945, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division pushed into the northern outskirts of Manila and the 8th Cavalry passed through the northern suburbs and into the city itself.

As the advance on Manila continued from the north and the south, the Bataan Peninsula was rapidly secured. On 16 February paratroopers and amphibious units assaulted the island fortress of Corregidor, and resistance ended there on 27 February.

In all, ten US divisions and five independent regiments battled on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific War, involving more troops than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France. Forces included the Mexican Escuadrón 201 fighter squadron as part of the Fuerza Aérea Expedicionaria Mexicana (FAEM—"Mexican Expeditionary Air Force"), with the squadron attached to the 58th Fighter Group of the United States Army Air Forces that flew tactical support missions. Of the 250,000 Japanese troops defending Luzon, 80 percent died. The last Japanese soldier in the Philippines to surrender was Hiroo Onoda on 9 March 1974.

Palawan Island, between Borneo and Mindoro, the fifth largest and western-most Philippine Island, was invaded on 28 February with landings of the Eighth Army at Puerto Princesa. The Japanese put up little direct defense of Palawan, but cleaning up pockets of Japanese resistance lasted until late April, as the Japanese used their common tactic of withdrawing into the mountain jungles, dispersed as small units. Throughout the Philippines, US forces were aided by Filipino guerrillas to find and dispatch the holdouts.

The US Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao (17 April), the last of the major Philippine Islands to be taken. Mindanao was followed by invasion and occupation of Panay, Cebu, Negros and several islands in the Sulu Archipelago. These islands provided bases for the US Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces to attack targets throughout the Philippines and the South China Sea.

Final Stages

Nazi Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945. General Alfred Jodl, representing the German High Command, signed a document unconditionally surrendering all German military forces, to take effect the following day, thereby all but ending World War II in Europe. However, the war in the Pacific continued without any sign of a Japanese surrender.

Leyte Gulf, 1944

The Battle of Iwo Jima ("Operation Detachment") in February 1945 was one of the bloodiest battles fought by the Americans in the Pacific War. Iwo Jima is an 8 sq mile (21 km2) island situated halfway between Tokyo and the Mariana Islands. Holland Smith, the commander of the invasion force, aimed to capture the island and prevent its use as an early-warning station against air raids on the Japanese Home Islands, and to use it as an emergency landing field. Lt. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the commander of the defense of Iwo Jima, knew that he could not win the battle, but he hoped to make the Americans suffer far more than they could endure.

From early 1944 until the days leading up to the invasion, Kuribayashi transformed the island into a massive network of bunkers, hidden guns, and 11 mi (18 km) of underground tunnels. The heavy American naval and air bombardment did little but drive the Japanese further underground, making their positions impervious to enemy fire. Their pillboxes and bunkers were all connected so that if one was knocked out, it could be reoccupied again. The network of bunkers and pillboxes greatly favored the defender.

Starting in mid-June 1944, Iwo Jima came under sustained aerial bombardment and naval artillery fire. However, Kuribayashi's hidden guns and defenses survived the constant bombardment virtually unscathed. On 19 February 1945, some 30,000 men of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions landed on the southeast coast of Iwo, just under Mount Suribachi; where most of the island's defenses were concentrated. For some time, they did not come under fire. This was part of Kuribayashi's plan to hold fire until the landing beaches were full. As soon as the Marines pushed inland to a line of enemy bunkers, they came under devastating machine gun and artillery fire which cut down many of the men. By the end of the day, the Marines reached the west coast of the island, but their losses were appalling; almost 2,000 men killed or wounded.

On 23 February, the 28th Marine Regiment reached the summit of Suribachi, prompting the now famous Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima picture. Navy Secretary James Forrestal, upon seeing the flag, remarked "there will be a Marine Corps for the next 500 years". The flag raising is often cited as the most reproduced photograph of all time and became the archetypal representation not only of that battle, but of the entire Pacific War. For the rest of February, the Americans pushed north, and by 1 March, had taken two-thirds of the island. But it was not until 26 March that the island was finally secured. The Japanese fought to the last man, killing 6,800 Marines and wounding nearly 20,000 more. The Japanese losses totaled well over 20,000 men killed, and only 1,083 prisoners were taken. Historians debate whether it was strategically worth the casualties sustained.

Okinawa

The largest and bloodiest American battle came at Okinawa, as the US sought airbases for 3,000 B-29 bombers and 240 squadrons of B-17 bombers for the intense bombardment of Japan's home islands in preparation for a full-scale invasion in late 1945. The Japanese, with 115,000 troops augmented by thousands of civilians on the heavily populated island, did not resist on the beaches—their strategy was to maximize the number of soldier and Marine casualties, and naval losses from Kamikaze attacks. After an intense bombardment the Americans landed on 1 April 1945 and declared victory on 21 June. The supporting naval forces were the targets for 4,000 sorties, many by Kamikaze suicide planes. US losses totaled 38 ships of all types sunk and 368 damaged with 4,900 sailors killed. The Americans suffered 75,000 casualties on the ground; 94% of the Japanese soldiers died along with many civilians.

The British Pacific Fleet operated as a separate unit from the American task forces in the Okinawa operation. Its objective was to strike airfields on the chain of islands between Formosa and Okinawa, to prevent the Japanese reinforcing the defences of Okinawa from that direction.

Landings in the Japanese Home Islands

Hard-fought battles on the Japanese home islands of Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and others resulted in horrific casualties on both sides but finally produced a Japanese defeat. Of the 117,000 Okinawan and Japanese troops defending Okinawa, 94 percent died.[158] Faced with the loss of most of their experienced pilots, the Japanese increased their use of kamikaze tactics in an attempt to create unacceptably high casualties for the Allies. The US Navy proposed to force a Japanese surrender through a total naval blockade and air raids.

Towards the end of the war as the role of strategic bombing became more important, a new command for the United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific was created to oversee all US strategic bombing in the hemisphere, under United States Army Air Forces General Curtis LeMay. Japanese industrial production plunged as nearly half of the built-up areas of 67 cities were destroyed by B-29 firebombing raids. On 9–10 March 1945 alone, about 100,000 people were killed in a conflagration caused by an incendiary attack on Tokyo. LeMay also oversaw Operation Starvation, in which the inland waterways of Japan were extensively mined by air, which disrupted the small amount of remaining Japanese coastal sea traffic. On 26 July 1945, the President of the United States Harry S. Truman, the President of the Nationalist Government of China Chiang Kai-shek and the Prime Minister of Great Britain Winston Churchill issued the Potsdam Declaration, which outlined the terms of surrender for the Empire of Japan as agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference. This ultimatum stated that, if Japan did not surrender, it would face "prompt and utter destruction."

Atomic bombs

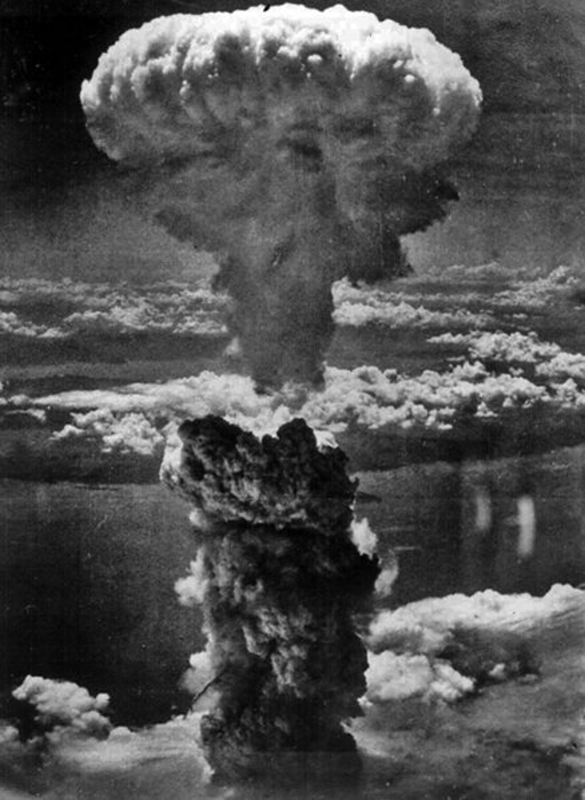

On 6 August 1945, the US dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in the first nuclear attack in history. In a press release issued after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Truman warned Japan to surrender or "...expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth."Three days later, on 9 August, the US dropped another atomic bomb on Nagasaki, the last nuclear attack in history. More than 140,000–240,000 people died as a direct result of these two bombings. The necessity of the atomic bombings has long been debated, with detractors claiming that a naval blockade and aerial bombing campaign had already made invasion, hence the atomic bomb, unnecessary. However, other scholars have argued that the bombings shocked the Japanese government into surrender, with Emperor finally indicating his wish to stop the war. Another argument in favor of the atomic bombs is that they helped avoid Operation Downfall, or a prolonged blockade and bombing campaign, any of which would have exacted much higher casualties among Japanese civilians. Historian Richard B. Frank wrote that a Soviet invasion of Japan was never likely because they had insufficient naval capability to mount an amphibious invasion of Hokkaidō

Surrender

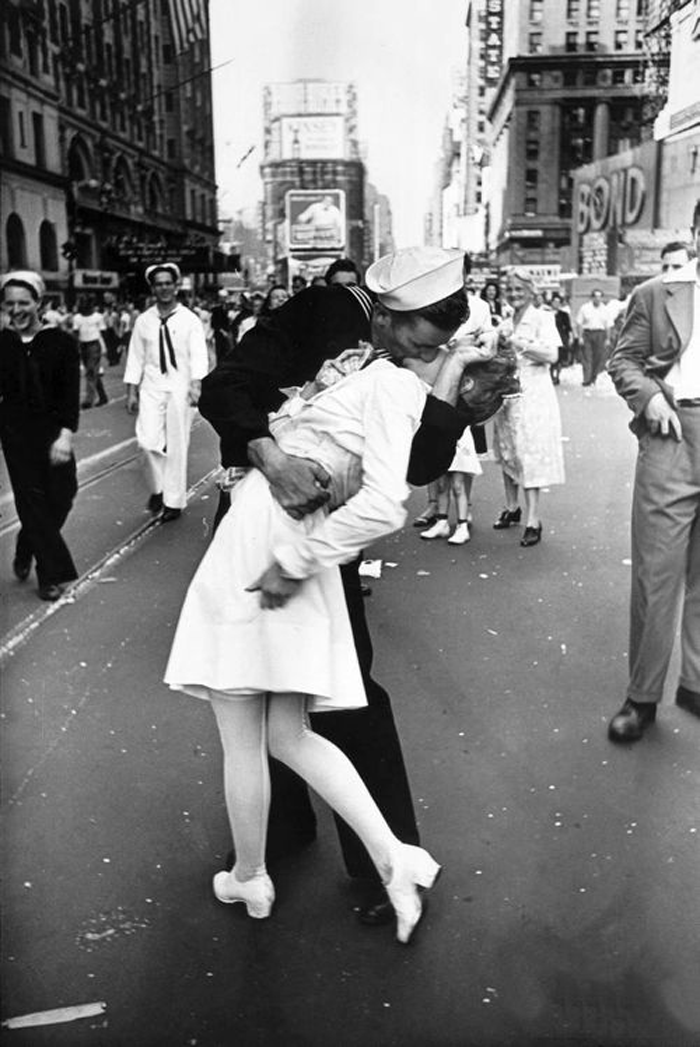

The effects of the "Twin Shocks"—the Soviet entry and the atomic bombings—were profound. On 10 August the "sacred decision" was made by Japanese Cabinet to accept the Potsdam terms on one condition: the "prerogative of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler". At noon on 15 August, after the American government's intentionally ambiguous reply, stating that the "authority" of the emperor "shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers", the Emperor broadcast to the nation and to the world at large the rescript of surrender, ending the Second World War.

"Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization."

In Japan, 14 August is considered to be the day that the Pacific War ended. However, as Imperial Japan actually surrendered on 15 August, this day became known in the English-speaking countries as V-J Day (Victory in Japan). The formal Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed on 2 September 1945, on the battleship USS Missouri, in Tokyo Bay. The surrender was accepted by General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, with representatives of several Allied nations, from a Japanese delegation led by Mamoru Shigemitsu and Yoshijirō Umezu.

Following this period, MacArthur went to Tokyo to oversee the post-war development of the country. This period in Japanese history is known as the occupation.

Casualties

United States

There were some 426,000 American casualties: 161,000 dead (including 111,914 in battle and 49,000 non-battle), 248,316 wounded, and 16,358 captured (not counting POWs who died). Material losses were 188+ warships including 5 battleships, 11 aircraft carriers, 25 cruisers, 84 destroyers and destroyer escorts, and 63 submarines, plus 21,255 aircraft. This gave the USN a 2-1 exchange ratio with the IJN in terms of ships and aircraft.

The US protectorate in the Philippines suffered considerable losses. Military losses were 27,000 dead (including POWs), 75,000 living POWs, and an unknown number wounded, not counting irregulars that fought in the insurgency. Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Filipino civilians died due to either war-related shortages or Japanese war crimes.

Japanese

800,000 Japanese civilians and over 2 million Japanese soldiers died during the war. According to a report compiled by the Relief Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare in March 1964, combined Japanese Army and Navy deaths during the war (1937–45) numbered approximately 2,121,000 men, mostly against either the Americans (1.1+ million) in places such as the Solomons, Japan, Taiwan, the Central Pacific, and the Philippines, or against various Chinese factions (500,000+), predominantly the NRA and CCP, during the war on the Chinese mainland, the Chinese resistance movement in Manchuria and Burma campaign.

The IJN lost over 341 warships, including 11 battleships, 25 aircraft carriers, 39 cruisers, 135 destroyers, and 131 submarines, almost entirely in action against the United States Navy. The IJN and IJA together lost some 45,125 aircraft.

War Crimes

On 7 December 1941, 2,403 non-combatants (2,335 neutral military personnel and 68 civilians) were killed and 1,247 wounded during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Because the attack happened without a declaration of war or explicit warning, it was judged by the Tokyo Trials to be a war crime.

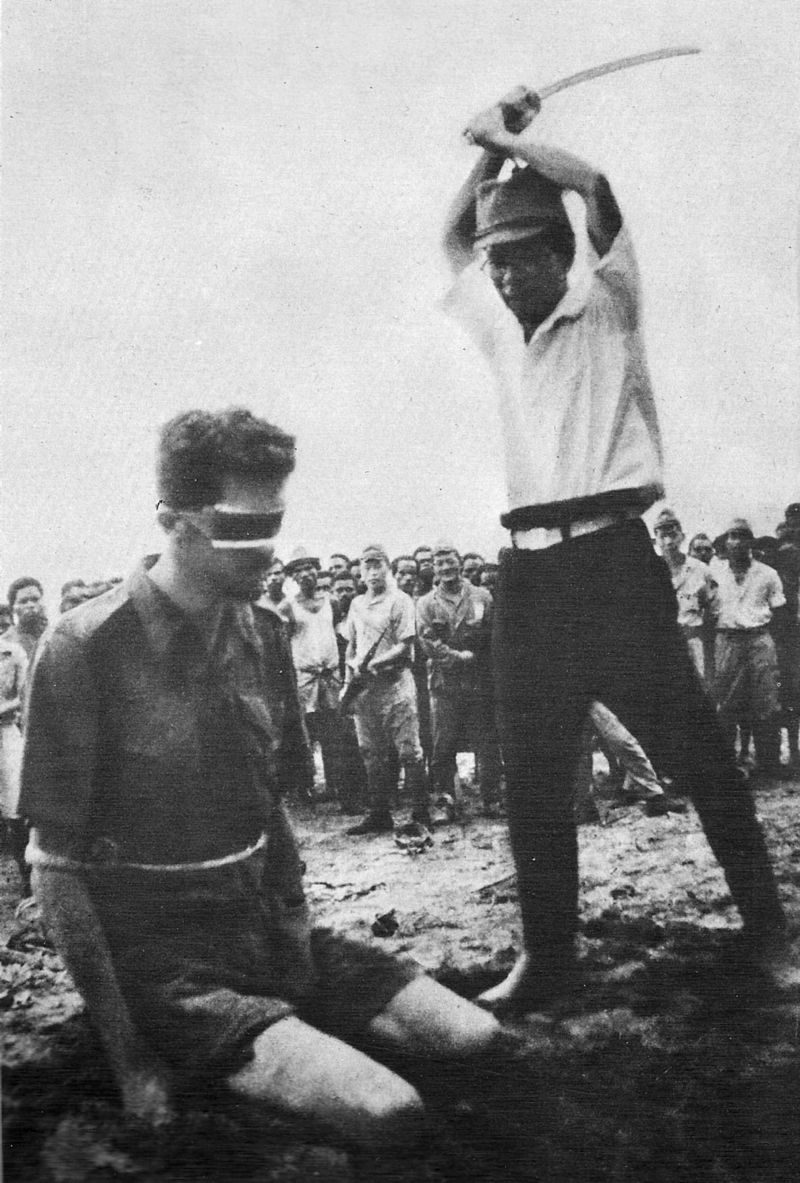

During the Pacific War, Japanese soldiers killed millions of non-combatants, including prisoners of war, from surrounding nations. At least 20 million Chinese died during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).

Unit 731 was one example of wartime atrocities committed on a civilian population during World War II, where experiments were performed on thousands of Chinese and Korean civilians as well as Allied prisoners of war. In military campaigns, the Imperial Japanese Army used biological weapons and chemical weapons on the Chinese, killing around 400,000 civilians. The Nanking Massacre is another example of atrocity committed by Japanese soldiers on a civilian population.

According to the findings of the Tokyo Tribunal, the death rate of Western prisoners was 27%, some seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians. The most notorious use of forced labour was in the construction of the Burma–Thailand "Death Railway." Around 1,536 U.S. civilians were killed or otherwise died of abuse and mistreatment in Japanese internment camps in the Far East; in comparison, 883 U.S. civilians died in German internment camps in Europe.

A widely publicised example of institutionalised sexual slavery are "comfort women", a euphemism for the 200,000 women, mostly from Korea and China, who served in the Imperial Japanese Army's camps during World War II. Some 35 Dutch comfort women brought a successful case before the Batavia Military Tribunal in 1948. In 1993, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yōhei Kōno said that women were coerced into brothels run by Japan's wartime military. Other Japanese leaders have apologized, including former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2001. In 2007, then-Prime Minister Shinzō Abe asserted: "The fact is, there is no evidence to prove there was coercion."

The Three Alls Policy (Sankō Sakusen) was a Japanese scorched earth policy adopted in China, the three alls being: "Kill All, Burn All and Loot All". Initiated in 1940 by Ryūkichi Tanaka, the Sankō Sakusen was implemented in full scale in 1942 in north China by Yasuji Okamura. According to historian Mitsuyoshi Himeta, the scorched earth campaign was responsible for the deaths of "more than 2.7 million" Chinese civilians.

The collection of skulls and other remains of Japanese soldiers by Allied soldiers was shown by several studies to have been widespread enough to be commented upon by Allied military authorities and US wartime press.

Following the surrender of Japan, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East took place in Ichigaya, Tokyo from 29 April 1946 to 12 November 1948 to try those accused of the most serious war crimes. Meanwhile, military tribunals were also held by the returning powers throughout Asia and the Pacific for lesser figures.

General MacArthur's Statement

"We are gathered here, representatives of the major warring powers—to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored. The issues involving divergent ideals and ideologies, have been determined on the battlefields of the world and hence are not for our discussion or debate. Nor is it for us here to meet, representing as we do a majority of the people of the earth, in a spirit of distrust, malice or hatred. But rather it is for us, both victors and vanquished, to rise to that higher dignity which alone befits the sacred purposes we are about to serve, committing all our people unreservedly to faithful compliance with the obligation they are here formally to assume. It is my earnest hope and indeed the hope and indeed the hope of all mankind that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past—a world founded upon faith and understanding—a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish—for freedom, tolerance and justice. The terms and conditions upon which the surrender of the Japanese Imperial Forces is here to be given and accepted are contained in the Instrument of Surrender now before you. As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, I announce it my firm purpose, in the tradition of the countries I represent, to proceed in the discharge of my responsibilities with justice and tolerance, while taking all necessary dispositions to insure that the terms of surrender are fully, promptly and faithfully complied with."

Source: Wikipedia

Summary

Date:

Location:

Result:

Territorial

changes:

7 December 1941 – 2 September 1945

(3 years, 8 months, 3 weeks and 5 days)

East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, Western Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean

Allied Victory

- End of World War II

- Fall of the Japanese Empire

- Continuation of the Chinese Civil War

- Substantial weakening of European colonial powers and the gradual decolonization of Asia

- First Indochina War

- Indonesian National Revolution

- Korean War

- 1951 Treaty of San Francisco

- 1956 Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration

Allied occupation of Japan

- Removal of all Japanese troops occupying parts of the Republic of China and the retrocession of Taiwan to China

- Liberation of Korea and Manchuria from Japanese rule, followed by the division of Korea

- Cession of all Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific Ocean to the United Nations

- Removal of all Japanese troops from the Australian-governed Solomon Islands and the territories of New Guinea and Papua

- Seizure and annexation of South Sakhalin and of the Kuril Islands by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands is placed under the authority of the United States of America. When the territory fell apart the US gained the territory of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Pacific War Maps

Click on any image to zoom

Allied attack routes against the Empire of Japan

Map of Pacific Theater commands, as defined by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Map of Pacific Theater commands, as defined by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Political map of the Asia-Pacific region, 1939.

Japanese advance until mid-1942.

Major battles of the Pacific War.

Photographs

Click on any image to zoom

USS Arizona burned for two days after being hit by a Japanese bomb in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

HMS Prince of Wales (left, front) and HMS Repulse (left, rear) under attack by Japanese aircraft. A destroyer is in the foreground.

The Bombing of Darwin, Australia, 19 February 1942.

Surrender of US forces at Corregidor, Philippines, May 1942.

A B-25 bomber taking off from the USS Hornet as part of the Doolittle Raid.

Australian POW moments before his execution

The aircraft carrier USS Lexington explodes on 8 May 1942, several hours after being damaged by a Japanese carrier air attack. Some 216 crewmen were killed and 2,735 were evacuated.

U.S. Marines in full battle kits charge ashore on Guadalcanal. The U.S, Navy got the Marines ashore on Guadacanal, but keeping them supplied proved to be a daunting task leading to a series of closely fought naval engagements off and around the Island. The American action on Guadalcanal was the first Allied offensive action in the Pacific (August 1942). The Japanese did not believe an American offensive was possible until mid-1943 and thus surprises. As a result, they did not at first perceive the importance, thinking it was a small force raid like Aaken Island which occurred at he sme time. The American perimiter was at first vulnerable. The Japanese could have won the battle, but their commanders instead of building up and concentrating their force for a major assault, disipated manpower in suisidal Banzai charges. The American success was critical. The Catus Air Force operatng from Henderson field prevented Japanese daylight naval attacks at a time that the Pacific Fleet was sorely streached and the new Essex-class carriers had not yet begun to reach the Fleet.

U.S. 5th Marines evacuate injured personnel during actions on Guadalcanal on November 1, 1942.

Attack transport USS President Jackson (APA-18) maneuvering under a Japanese air attack during the Battle of Guadalcanal, November 1942.

Australian commandos in New Guinea during July 1943

An SBD Dauntless flies patrol over USS Washington and USS Lexington during the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, November 12, 1943.

The torpedoed Yamakaze, as seen through the periscope of an American submarine, Nautilus, in June 1942

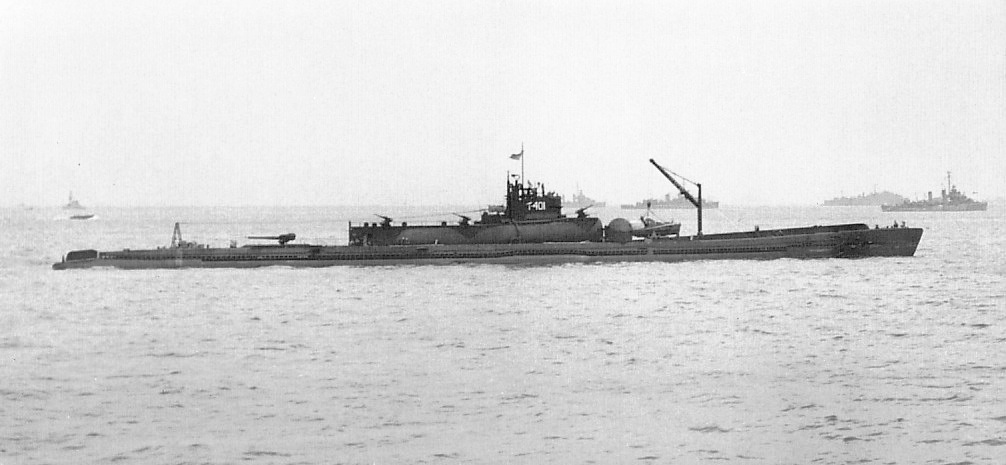

The Imperial Japanese Navy's I-400 class, the largest non-nuclear submarines ever constructed.

Naval transports (Higgins boats) at the Battle of Tarawa (20–23 November 1943). The Battle of Tarawa was the first American offensive in the critical central Pacific region. It was also the first time in the Pacific War that the United States had faced serious Japanese opposition to an amphibious landing. Previous landings met little or no initial resistance, but on Tarawa the 4,500 Japanese defenders were well-supplied and well-prepared, and they fought almost to the last man, exacting a heavy toll on the United States Marine Corps. The losses on Tarawa were incurred within 76 hours.

"On Tarawa Beach-Marines landing on Tarawa Island beach creep up on Jap pill boxes. The terrain of the island offered very little protective covering but these Marines made use of what little covering there was. Some of the Jap troops in pill boxes held out for two days before they surrendered or were blasted out." From the General Julian C. Smith Collection, Marine Corps Archives

American corpses sprawled on the beach of Tarawa, November 1943. President Roosevelt authorized release of such photos (and video) to highlight the severity of the war in the Pacific against the Japanese. He believed the time had come for the American public to see what combat was really like. The film footage was an essential part of the Oscar–winning documentary With the Marines at Tarawa. The sale of war bonds rose after the film’s release.

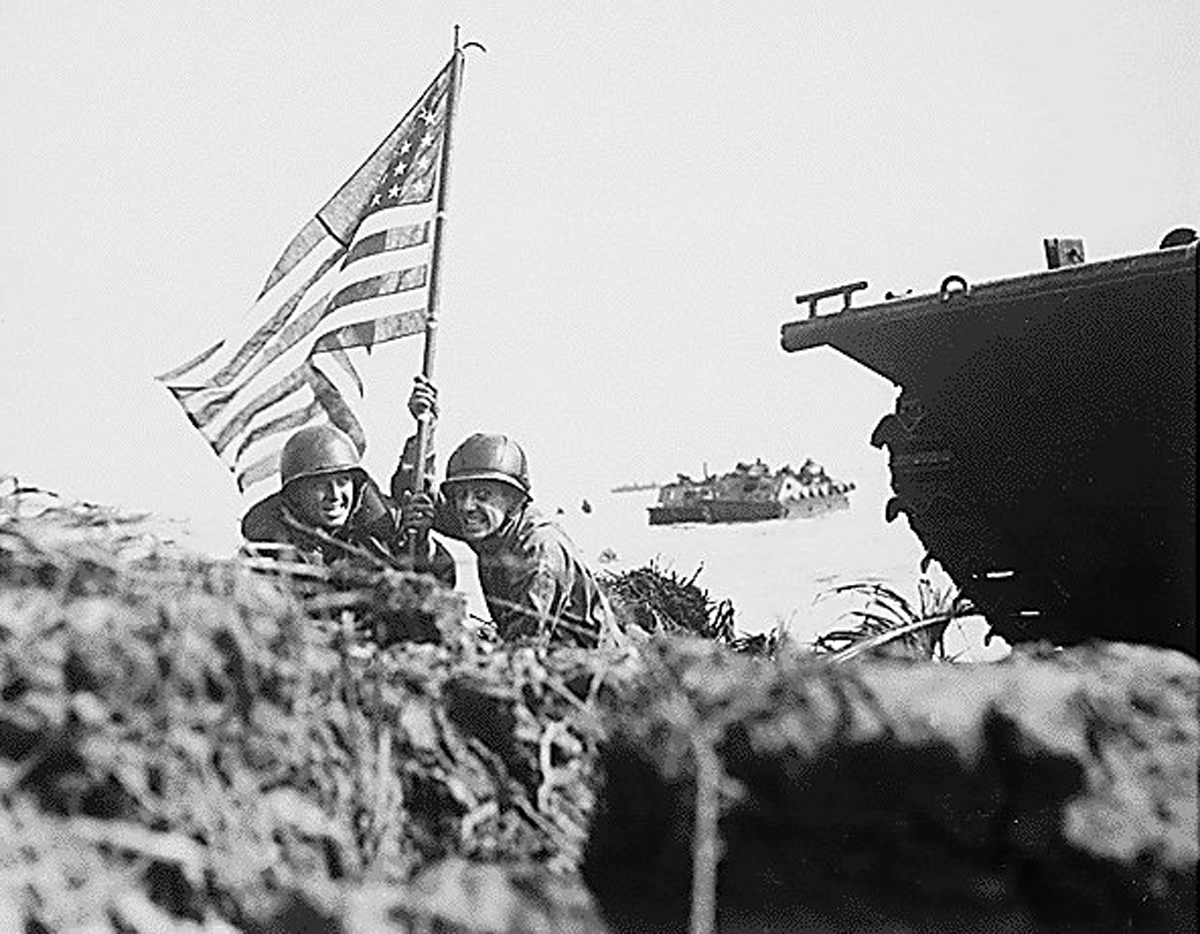

Marine Captains Paul O'Neal (left) and Milton Thompson (right) plant the American flag eight minutes after U.S. Marine and Army troops landed on Guam, 21 July 1944.

Transports steam in column off Pavuvu, Russell Islands, August 1944, probably during exercises preceding the Palaus operation (Battle of Peleliu). Photographed from USS Fayette (APA-43) looking forward, showing her kingposts and LCVPs stowed on deck. USS Pinkney (APH-2) is leading the column, followed by USS Elmore (APA-42) and USS DuPage (APA-41).

USS Elmore (APA-42) hoisting an LCVP on A-day at Leyte Island, Philippine Islands, 20 October 1944.

3rd Bn, 19th Inf. Reg disembarking from USS Elmore (APA-42) before hitting the beach at Leyte. Note landing craft circling near Elmore, awaiting their turn to load troops and then waiting for the signal to form waves.

The battleship USS New York firing its 14 in (360 mm) main guns on the island, 16 February 1945 (D minus 3), Battle of Iwo Jima.

U.S. Marines fire a .37 mm (1.5 in) gun against Japanese cave positions in the north face of Mount Suribachi, Battle of Iwo Jima, 19 February 1945.

Marines landing on the beach, Battle of Iwo Jima, 19 February 1945.

B-29 Superfortress bombers of the 462nd Bomb Group taxiing through West Field, Tinian, Mariana Islands, 1945.

General Douglas MacArthur landing at Luzon, Philippines, 9 January 1945. The Battle of Luzon resulted in a U.S. and Filipino victory. The Allies had taken control of all strategically and economically important locations of Luzon by March 1945, although pockets of Japanese resistance held out in the mountains until the unconditional surrender of Japan. While not the highest in U.S. casualties, it is the highest net casualty battle U.S. forces fought in World War II, with 200,000 Japanese combatants dead, 8,000 American combatants killed, and over 150,000 Filipinos, overwhelmingly civilians, who were murdered by Japanese forces, mainly during the Manila massacre of February 1945.

US troops approaching Japanese positions near Baguio, Luzon, 23 March 1945.

A 6th Marine Division demolition crew watches explosive charges detonate and destroy a Japanese cave, May 1945, at the Battle of Okinawa. The initial invasion of Okinawa on 1 April 1945, was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The battle has been called the "typhoon of steel," referring to the ferocity of the fighting, the intensity of Japanese kamikaze attacks and the sheer numbers of Allied ships and armored vehicles that assaulted the island. The battle was one of the bloodiest in the Pacific war and was the final battle before the surrender of Japan.

USS Bunker Hill burns after being hit by two kamikazes. At Okinawa, the kamikazes caused 4,900 American deaths.

USS Enterprise (CV-6) was a Yorktown-class carrier. Colloquially called "The Big E", she was the sixth aircraft carrier of the United States Navy. Launched in 1936, she was one of only three American carriers commissioned before World War II to survive the war (the others being Saratoga and Ranger). She participated in more major actions of the war against Japan than any other United States ship. These actions included the Battle of Midway, the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, various other air-sea engagements during the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Enterprise earned 20 battle stars, the most for any U.S. warship in World War II, and was the most decorated U.S. ship of World War II. On three occasions during the war, the Japanese announced that she had been sunk in battle, inspiring her nickname "The Grey Ghost". By the end of the war, her planes and guns had downed 911 enemy planes, sunk 71 ships, and damaged or destroyed 192 more.

Mushroom cloud from the second atomic bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, 9 August 1945. Three days prior, the first atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima.

US Army General MacArthur Arrives at Atsugi Airfield, August 30, 1945, placed in charge of the surrender and occupation of Japan, under the title Supreme Commander Allied Powers (SCAP). Though the first two weeks of this mission were directed from Manila, on August 30 MacArthur flew to Japan. Without escort and only armed with sidearms, his small party wondered if they would be killed or captured upon landing, but MacArthur was confident the Japanese were genuine in their surrender and the mission would be welcomed. Arriving at Atsugi airfield, he established temporary headquarters some twenty miles away, at the Tokyo Bay city of Yokohama. Arrangements for the formal surrender ceremonies were made there. SCAP headquarters moved to Tokyo on September 8, beginning six years of occupation government from the Japanese capital city.

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, signs the Instrument of Surrender as United States Representative, on board USS Missouri (BB-63), 2 September 1945.