Tokyo Rose

Trapped in Japan

Radio propaganda was rampant on all sides of World War II, but perhaps no broadcaster was as infamous as Iva Toguri - better known to her Allied listeners as "Tokyo Rose." The American-born Toguri became stranded in Japan when the war began, and she was eventually coaxed behind the microphone and instructed to read radio scripts aimed at demoralizing U.S. troops in the Pacific. Toguri always maintained that she was a loyal American who had been forced onto the radio by circumstance, but after the war ended she was convicted of treason and sentenced to several years in prison. Despite a lack of evidence against her, it would take nearly three decades before she received a presidential pardon. This is her story.

Although nearly a dozen female broadcasters were given the moniker "Tokyo Rose" during World War II, Toguri became most associated with the name, which along with Hideki Tojo came to personify infamy in the Pacific. As the female Japanese announcers did not reveal their name, they were quickly dubbed by the American troops: Tokyo Rose, Orphan Annie (Iva Toguri), Manila Rose, The Nightingale of Nanking (Ruth Hayakawa) and Madame Tojo (Foumy Saisho).

Iva Toguri was born Ikuko Toguri in Los Angeles, California on Independence Day, July 4, 1916. She was the daughter of Japanese immigrants who owned a small import business in Los Angeles. During her school years, Ikuko Toguri started using Iva as her first name. She had spent her youth serving in the Girl Scouts and playing on her school’s tennis team, and later graduated from UCLA with a zoology degree. As a graduation gift her parents sent Iva to Japan to visit her sick aunt.

On July 5, 1941, Toguri sailed for Japan from San Pedro, California, without a U.S. passport. In subsequent years, she gave two reasons for her trip: to visit a sick aunt and to study medicine as she hoped someday to become a doctor.

The 25-year-old Toguri had never been abroad before and quickly grew homesick. She didn’t like the food and felt very alien. In September of that year, Toguri appeared before the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan to obtain a passport so she could return home. Because she left the U.S. without a passport, her application was forwarded to the Department of State for consideration. Before arrangements were completed for issuing her a passport, Japan bombed Pear Harbor and war was declared.

Iva later withdrew the application, saying she would voluntarily remain in Japan for the duration of the war. She enrolled in a Japanese language and culture school to improve her language skills.

With war starting with the United States Toguri found herself trapped in Japan. She could no longer stay with her aunt's family as she was an American citizen. At the same time she could not receive any aid from her parents as they had been placed in internment camps in Arizona. Recognizing her vulnerability, the Japanese military police tried to persuade her to renounce her U.S. citizenship and swear allegiance to Japan—a route many other Americans in Japan took—but she refused. As a result, she was classified as an enemy alien and was denied a food ration card. Her movements were also closely monitored. Toguri spent the next several months living with her relatives, but frequent harassment by neighbors and military police eventually led her to move to Tokyo. From mid-1942 until late 1943, Toguri worked as a typist for the Domei News Agency; in August 1943, she obtained a second job as a typist for Radio Tokyo. (NHK).

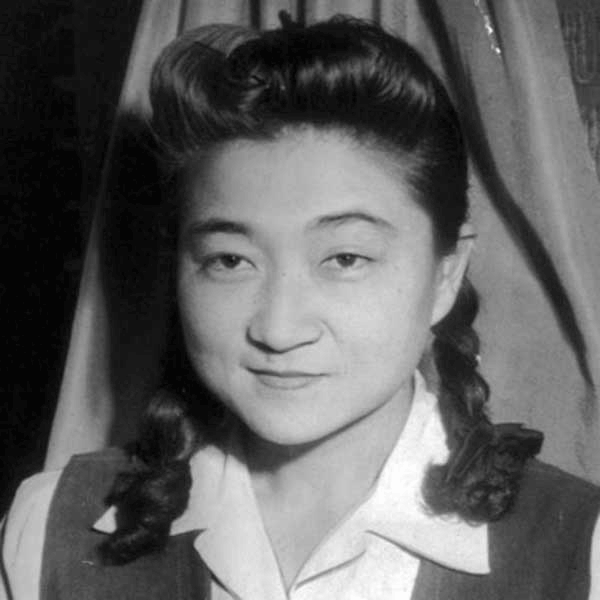

Iva Toguri D'Aquino

Photo of Iva Toguri taken outside Radio Tokyo on 5 December 1944

The Radio Broadcasts

Major Cousens had become friendly with Iva Toguri, a Japanese-American girl, who, stranded and unable to return to California, had found some suitable typing work with NHK. Iva was pro-American. Cousens selected Iva to work as an announcer on his radio show, though meeting with a little opposition initially from his Japanese superiors. Cousens knew what he was doing, he wanted a genuine American female voice to join his team, which now comprised eight in all.

It was at Radio Tokyo that Toguri met Major Charles Cousens, an Australian military officer who had been captured in Singapore. Cousens had been a successful radio announcer before the war, and he was now being forced to produce the propaganda show the “Zero Hour” for the Japanese. In defiance of their captors, he and his fellow POWs had been working to sabotage the program by making its message as laughable and harmless as possible. Major Cousens had become friendly with Iva Toguri, a Japanese-American girl, who, stranded and unable to return to California, had found some suitable typing work with NHK. Iva was pro-American. Cousens selected Iva to work as an announcer on his radio show, though meeting with a little opposition initially from his Japanese superiors. Cousens knew what he was doing, he wanted a genuine American female voice to join his team as a radio announcer. He later said:

"With the idea that I had in mind of making a complete burlesque of the program, her voice was just what I wanted, It was rough, almost masculine, nothing of a femininely seductive voice. It was the comedy voice that I needed for this particular job."

Iva Toguri accepted the job at a rate of 150 Yen per month--about $7 in U.S. currency. By so doing, she had taken the first step along the road to being branded as a traitor.

The program originated in NHK studios in Japan, and was beamed to different theaters of war over NHK short-wave transmitters.

Iva Toguri called herself "Orphan Annie". The word 'orphan' was often used in Japanese broadcasts to describe the fate of the Australian forces, caught up in a war not of their own making, sent to defend Singapore, captured and abandoned to their fate by the British.

A typical 'Orphan Annie' broadcast, August 14, 1944:

"Hello, you fighting orphans of the Pacific. This is your little playmate Orphan Annie. How's tricks? This is after her weekend off, Annie is back on the air, strictly under union hours. Reception OK? Well, it better be, because this is all request night and I've got a pretty nice program for all my favorite little family, the wandering boneheads of the Pacific Islands."

Following the news section, she said:

"Thank you, thank you, thank you. Now, let's have some real listening music - you can have your swing when I turn you over to Zero Hour. Right now, my little orphans, do what mama tells you. Listen to this, Fritz Kreisler playing 'Indian Love Call'…..boy, oh boy, it stirs your memories doesn't it? Or haven't you boneheads any memories to stir? You have? Well, here's music 'In a Persian Market' played especially for you by the Boston Pops Orchestra…Orphan to orphan-over.

"You say you want to see me every night, But, every time you see me, you want to only fight, I have to say no . . ."

"According to union hours, we’re all through today. We close up another chapter of sweet propaganda in the form of music for you, for my dear little orphans wandering in the Pacific. There are plenty of non-union hours coming around the corner, so being see you tomorrow. But in the meanwhile, always remember to be good, and so . . .Good-bye now, Good-bye now, Good-bye now, Good-bye."

These broadcasts were believed to be scripted by Major Cousens, who coached Iva Toguri in reading technique. The scripted words "Thank you, thank you, thank you" and "Good-bye now, Good-bye now, Good-bye now, Good-bye" were later claimed to be used as a deliberate 'wipe out' device to clear the listeners mind of what has gone before. The program took advantage of slang, jokes and puns to get across his hidden message, that Zero Hour was really coming from one American soldier to another.

By mid-1944, Radio Tokyo NHK overseas broadcasting bureau had honed and crafted its skills in making authentic American-style radio programs. By patience and dedication, the Japanese had overcome all initial problems and were setting a new standard in radio propaganda, which was unequalled by anything existing.

While she was initially hesitant to get behind the microphone, Toguri eventually became a key participant in Cousens’ scheme. Starting in November 1943, her voice was a recurring feature on the “Zero Hour” broadcasts. Toguri adopted the radio handle “Orphan Ann” and grew adept at reading Cousens’ scripts in a joking manner, sometimes even warning her listeners that the show was propaganda:

"So be on your guard, and mind the children don’t hear! All set? Okay! Here’s the first blow at your morale—the Boston Pops playing ‘Strike Up the Band!'"

In another broadcast, Toguri called her listeners:

"My favorite family of boneheads, the fighting G.I.s in the blue Pacific."

The “Orphan Annie” show was a 15-20 minute D.J. segment of the 75-minute program The Zero Hour on Radio Tokyo (NHK). The program consisted of propaganda-tinged skits and slanted news reports as well as popular American music. Zero Hour was as good as anything that came out of America - it was well produced and directed. A typical hour's program included the following features:

- A loud opening number Strike Up the Band by the Boston Pops Orchestra

- Messages from POW's: Hi mom, this is Corporal X, we are OK but we need socks and food

- The Orphan Annie Show: 20 minutes of high quality American jazz and semi-classical records introduced by Annie

- American home-front news: tidbits picked up from America by Japanese monitoring stations

- Juke Box: 15-20 minutes of popular jazz

- Ted's news highlight tonight: more news from overseas SW broadcasts

- News summary: sometimes read by Charles Yoshii.

- Military marches

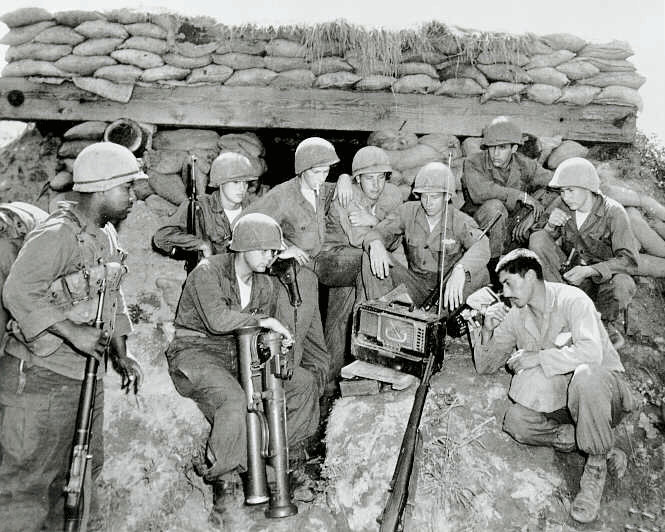

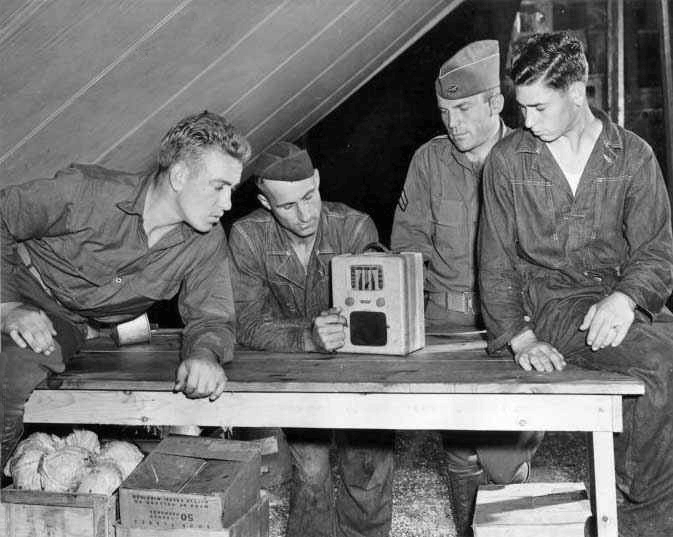

- The official view of the US government was that these programs were propaganda. This view was not always shared by its armed forces: reports from the US Navy in the Pacific thought that the Japanese broadcasts did a lot for the American soldier on the Pacific atolls. This view was certainly shared by the US Army, and the enlisted men who huddled around at the time of sunset to hear their favorite announcer.

Taunting millions of servicemen with stories of infidelity on the home front, false reports of battle outcomes meant to demoralize them and frequent spins of pop songs to keep them listening, the broadcasts of Radio Tokyo were deemed notorious instruments in the propaganda war.

It is interesting to note that Iva only spent twenty minutes a day broadcasting at Radio Tokyo. The rest of her time was spent as a typist and on scavenger hunts for black-market food, medicine and supplies for what she had come to regard as “her” POWs.

During World War II, American servicemen regularly huddled around radios to listen to the Zero Hour, an English-language news and music program that was produced in Japan and beamed out over the Pacific. The Japanese intended for the show to serve as morale-sapping propaganda, but most G.I.s considered it a welcome distraction from the monotony of their duties. They developed a particular fascination with the show’s husky-voiced female host, who dished out taunts and jokes in between spinning pop records. She said during one broadcast in 1944:

"Greetings, everybody! This is your little playmate—I mean your bitter enemy—Ann, with a program of dangerous and wicked propaganda for my victims in Australia and the South Pacific. Stand by, you unlucky creatures, here I go!"

She signed off one of her broadcasts by saying:

"According to union hours, we are through today! We close off another chapter of free propaganda in the form of ‘Music For You’—for my dear little orphans wandering in the Pacific. There are plenty of non-union boffs coming around the corner, so be seeing you tomorrow, but in the meanwhile always remember to be good!”

The surviving recordings and transcripts of Toguri’s programs indicate that she never threatened her listeners with bombings or taunted them about their wives being unfaithful—two favorite strategies of wartime propagandists.

Major Charles Cousens

Iva Toguri at the microphone on the air with The Zero Hour

Soldiers in the Pacific listening to The Zero Hour

American servicemen regularly gathered around radios to listen to The Zero Hour

Iva Toguri at the microphone as "Orphan Annie" on the air with The Zero Hour

"Orphan Annie" on the air with The Zero Hour

YouTube video: Radio Tokyo announcer Iva Toguri D'Aquino talks about her life in America and Japan. Click on the image of Iva above to watch the video.

The Zero Hour Winds Down

Things had changed at Radio Tokyo when Cousens was hospitalized following a heart attack and was taken off the air, the heart went out of Iva as well, but she carried on as best she could, re-writing Cousens’ old scripts as much as possible, writing in his flippant style, keeping the faith.

Toguri performed her “Orphan Ann” character on the “Zero Hour” for roughly a year and a half, but she appeared with less frequency as the war worsened. Her pro-American sentiment was tolerated less and less by her co-workers. As a result Iva quit her job at the radio station and found work at the Danish legation, where she took part of her pay in luxury items from the legation’s diplomatic rations, which she then traded on the black market for even more goods for the POWs.

On April 19, 1945, Iva Toguri married Felipe Aquino, a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry. Iva moved in with Felipe d’Aquino’s family in Atsugi and contrived to stay away from Radio Tokyo as much as possible. Various women filled in for her at this time, reading straight propaganda as in the other NHK programs. B-29s launched from China and Okinawa began to firebomb Tokyo for days on end. A month later, Iva was ordered by a plainclothesman to report back to Radio Tokyo. Three months later, the war was over.

Iva Toguri d’Aquino reportedly cheered as the Emperor’s broadcast on Radio Tokyo announced the unconditional surrender. She made plans for a triumphal return to America with Filipe. This would soon proved not to be the case.

At the time of the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Iva and her husband were in dire financial straits.

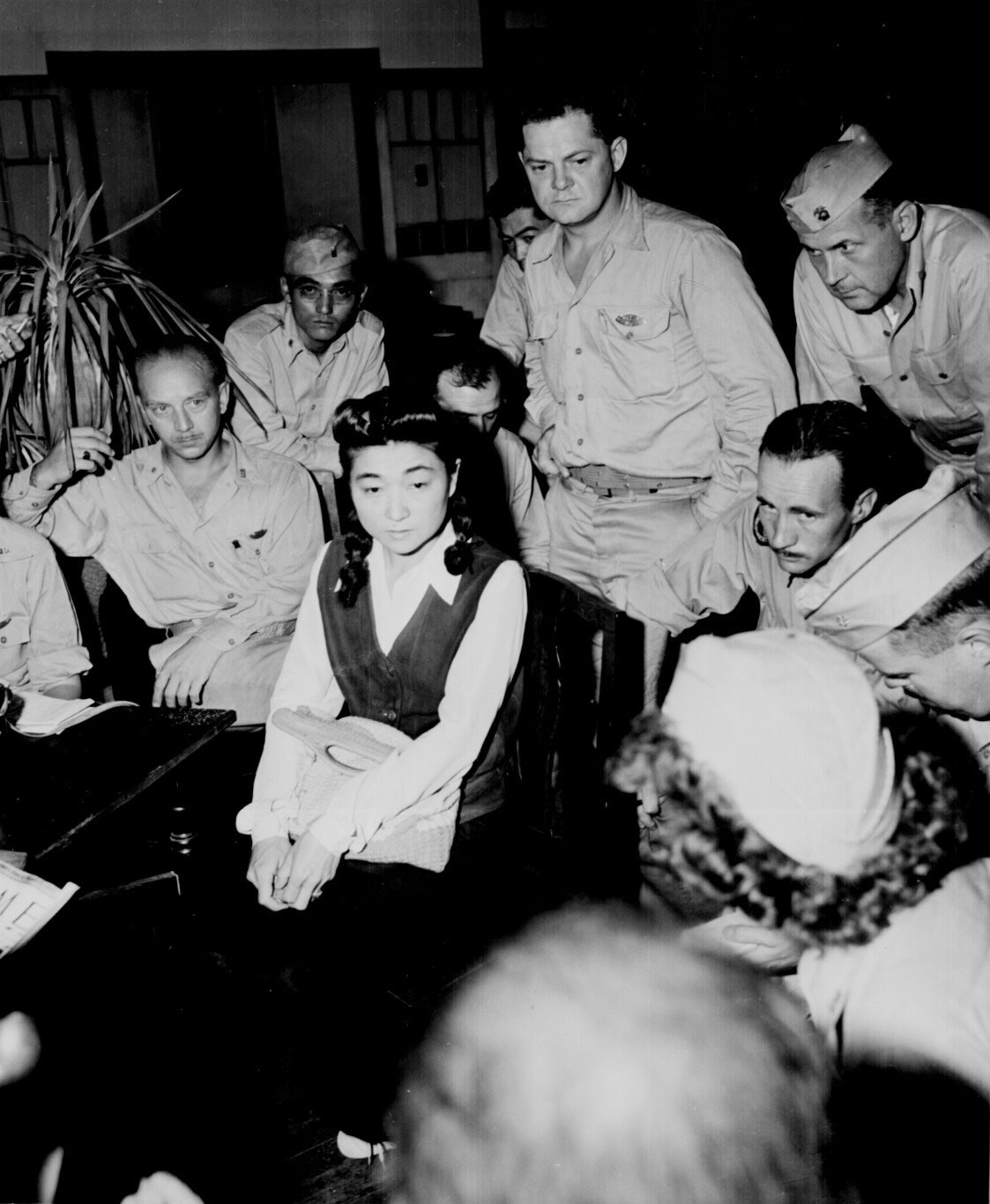

When General Douglas MacArthur’s plane set down at Atsugi on 30 August 1945, it also carried dozens of military and civilian reporters covering the historic event. Among them were Clark Lee of INS and Harry Brundidge of Cosmopolitan. These two reporters had joined forces to get the beat on the two most sought-after interviews in post-war Japan: Hideki Tojo and “Tokyo Rose.” The former was easy to find, he was under house arrest in Tokyo, but “Tokyo Rose” was a mystery.

Brundidge offered a $250 reward to anyone who could put him in touch with “Tokyo Rose” and $2,000 to “Rose” herself for an exclusive interview. The $250 reward was equal to $3,750 or about three year’s income. $2,000 was over $30,000—a fortune by either standard. Leslie Nakashima, a Nisei at Radio Tokyo, gave them Iva Toguri’s name, which Clark Lee promptly reported to the world at large. Iva Ikuko Toguri d’Aquino naively stepped forward and signed a contract identifying herself as Tokyo Rose. It would prove to be a disastrous decision. Once her identity became public, Toguri was made into the poster child for Japan’s wartime propaganda.

But Brundidge had jumped the gun. His editor at not only rejected the story, but also refused to authorize the $2,000 payment. The money would have to come out of Brundidge’s own pocket unless he could void the contract. He took Lee’s 17-page notes of the interview to 8th Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) Commanding General Elliot Thorpe and urged him to arrest Iva Toguri:

"She’s a traitor and here’s her confession."

He also suggested a mass news conference between Toguri and the other 300 reporters, which would negate the terms of his “exclusive” contract and allow him to escape payment.

Not knowing Brundidge’s hidden agenda, everyone agreed and Iva met with reporters at the Yokohama Bund Hotel. She subsequently gave interviews to Yank, Pacific Stars & Stripes and recorded a simulated “Orphan Ann” broadcasts for the American newsreels. Iva thought that “Tokyo Rose” was the popular darling of the GIs, as “Orphan Ann” had always been intended to be. She thought she was now a radio celebrity and happily signed autographs and posed for pictures as “Tokyo Rose.”

Iva cheerfully answered all the questions put to her by 8th Army CIC, laughing off suggestions that she might have done anything wrong in broadcasting for the Japanese. She was puzzled by questions about her giving predictions of troop movements and impending counterattacks, talk about wives in the arms of 4-Fs (Iva had never even heard the term “4-F” before, much less used it any of her broadcasts) and other such nonsense, but offered her Radio Tokyo scripts to set the record straight.

Meanwhile, back in the U.S., the news that “Tokyo Rose” was an American citizen who intended to return to her home in California sparked angry protests.

In September 1945, after the press had reported that Toguri was Tokyo Rose, U.S. Army authorities arrested her on suspicion of treason. The FBI and the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether Toguri had committed crimes against the U.S. She would remain in custody for over a year until a government investigation concluded that the evidence then known did not merit prosecution, and she was released.

Before the year was out, Toguri again requested a U.S. passport. American veterans groups and noted broadcaster Walter Winchell learned of this and became outraged that the woman they thought of as “Tokyo Rose” wanted to return to this country. They demanded that the woman they considered a traitor be arrested and tried, not welcomed back.

On 17 October 1945, Iva Toguri d’Aquino was washing her hair when three Counter Intelligence Corps officers arrived at her apartment in Setagaya and asked her to accompany them to Yokohama to answer a few more questions. As they were leaving, she was told that she might have to stay overnight and that she should bring a toothbrush.

Only after she arrived at the 8th Army HQ brig was she told that she was in fact under arrest, with no warrant and no charges. A debate ensued as to whether she was Japanese or American, to be fed rice or bread, to be given a futon or a cot.

She finally got the bread and the cot, but was kept awake for the next three days by a constant stream of curiosity-seekers and rowdy name-callers outside her cell. She was allowed one bucket of hot water every three days to bathe herself and launder her clothes. Felipe d’Aquino was denied a visitor’s pass when he tried to see her. One of her guards extorted a “Tokyo Rose” autograph from her by leaving the lights on in her cell for a week.

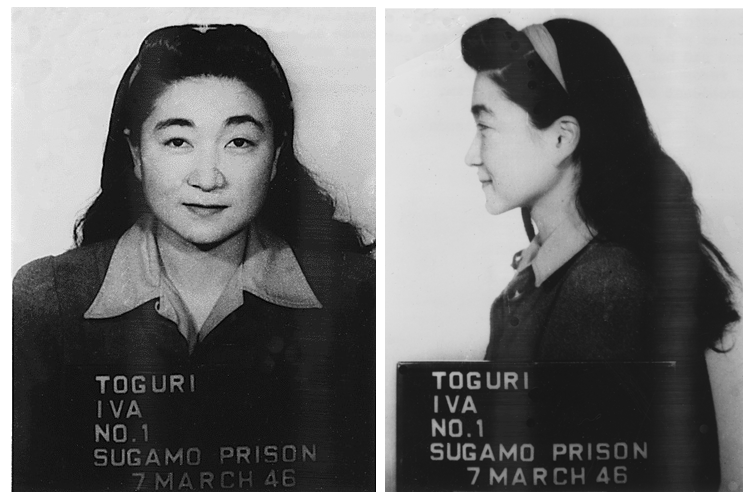

Iva’s arrest for treason was announced publicly, but Iva herself was never told the reason for which she was being held. A month later, she was transferred to Sugamo Prison and placed in a cell on “Blue Block,” where diplomats and women accused of war crimes were held. She spent the next eleven and a half months locked in a 6-by-9 cell, allowed only one 20-minute visit from Felipe on the first of each month and a bath every three days.

The public furor convinced the Justice Department that the matter should be re-examined, and the FBI was asked to turn over its investigative records on the matter. The FBI’s investigation of Toguri’s activities had covered a period of some five years. During the course of that investigation, the FBI had interviewed hundreds of former members of the U.S. Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II, unearthed forgotten Japanese documents, and turned up recordings of Toguri’s broadcasts. Many of these recordings, though, were destroyed following the initial decision not to prosecute Toguri in 1946.

Early in her imprisonment, she learned of her mother’s death enroute to the internment camp in Arizona and her family’s subsequent relocation to Chicago.

Iva and Felipe hid out for awhile, then she applied for a passport to return home, but was again frustrated by the lack of documentation that had gotten her stranded in Japan in the first place. Iva became pregnant in 1947 and vowed her child would be born in the U.S., but the baby died shortly after he was born in January 1948. It is likely that this loss, too, was a result of her imprisonment. She was physically exhausted and emotionally devastated by this tragic loss.

Toguri made an attempt to return home after her release, yet anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States remained high. Several influential figures—among them the legendary radio commentator Walter Winchell—began lobbying the government to reopen the case against her. The campaign worked.

The Department of Justice initiated further efforts to acquire additional evidence that might be sufficient to convict Toguri. It issued a press release asking all U.S. soldiers and sailors who had heard the Radio Tokyo propaganda broadcasts and who could identify the voice of the broadcaster to contact the FBI. Justice also sent one of its attorneys and reporter Harry Brundidge to Japan to search for other witnesses.

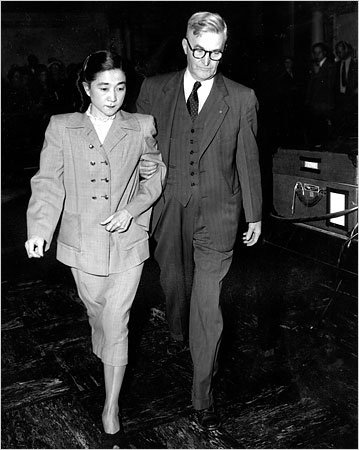

With new witnesses and evidence, the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco convened a grand jury, and Toguri was indicted on a number of counts in September 1948. She was detained in Japan and brought under military escort to the U.S., arriving in San Francisco on September 25, 1948. There, she was immediately arrested by FBI agents, who had a warrant charging her with the crime of treason for adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II.

Iva spent the next nine months awaiting trial in San Francisco County Jail, without bail. Feeling she had to stay busy and be of service to others, she helped out at breakfast and dinner, waiting on tables and cleaning up afterward. She worked as a clerk/typist in the Marshal's Office weekdays from 8am to 4pm and embroidered in her free time from 6 to 9pm, producing bright floral designs on three tablecloths for the jail dining hall. She had lost 30 pounds during the sea voyage and still suffered from chronic dysentery. Despite her own troubles, she earned the nickname "The Little Nurse" for her assistance and advice to the staff and other inmates.

Iva and her husband, Felipe D’Aquino, in Japan 1945

Iva Toguri D'Aquino being interviewed by reporters.

Mug shot of Iva Toguri taken at Sugamo Prison in March 1946

Sugamo Prison

Iva Toguri's release from Sugamo Prison

Iva Toguri after she was released from prison in 1946

Iva Toguri being escorted by Military Police

Iva Toguri behind bars

Walter Winchell (1897–1972) was a columnist, radio commentator and TV personality who pioneered gossip driven and politically charged journalism. At its peak around WWII, his audience was 50 million, two out of three American adults. By the mid-1950s, he was widely seen as arrogant, cruel, and ruthless. He was the motivating force behind the federal treason charges against Iva Toguri.

The Trial

The trial itself lasted 13 weeks and cost $750,000 (by today's standards, over $5 million); the most expensive trial in American history to that time. No one who had ever met Iva believed her guilty and the local press corps voted 9-to-1 among themselves for acquittal. The government brought in a parade of witnesses flown in from Japan with all expenses paid and a per-diem allowance that would give most of them a good start back home. The defense, paid for entirely by Iva's father, could only afford to bring in depositions from witnesses in Japan, many of whom had already been visited by the FBI and CIC. When the defense uncovered evidence of perjury in the grand jury that indicted Iva, the judge ruled it inadmissible on the grounds that the alleged perjurer wasn't testifying at the actual trial. All references to Iva's work with the POWs was ruled inadmissible as being irrelevant to the question of treason. Charles Cousens flew in at his own expense to testify on Iva's behalf.

Toguri stressed that she had remained loyal to the United States by working to make a farce of her broadcasts. Charles Cousens even came to the United States to testify on her behalf, but the prosecution produced a series of Japanese witnesses who claimed to have heard her make incendiary statements on the air. Much of the case centered on a single broadcast that occurred after the Battle of Leyte Gulf, when she was alleged to have said:

"Orphans of the Pacific, you are really orphans now. How will you get home now that your ships are sunk?"

This remark, which didn’t appear in any of her show transcripts, proved to be a deciding factor in the case. The jury could not arrive at a verdict. The judge told the jury that the trial had cost the U.S. government over a half million dollars and instructed them to resume deliberation and bring in a verdict. Their final determination was not guilty on seven counts, guilty on one:

That she did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships.

The minimum possible sentence was five years imprisonment and a $5,000 fine, the maximum sentence was death. No one expected the latter and the local press corps speculated that she would receive the minimum sentence and be out in three years. She was stripped of her American citizenship, given a $10,000 fine and sentenced to ten years behind bars. The judge, whose son had served in the Pacific during the war, later admitted to AP reporter Katherine Beebe Pinkham that he had been prejudiced against Iva from the start.

—————————————————————————————————

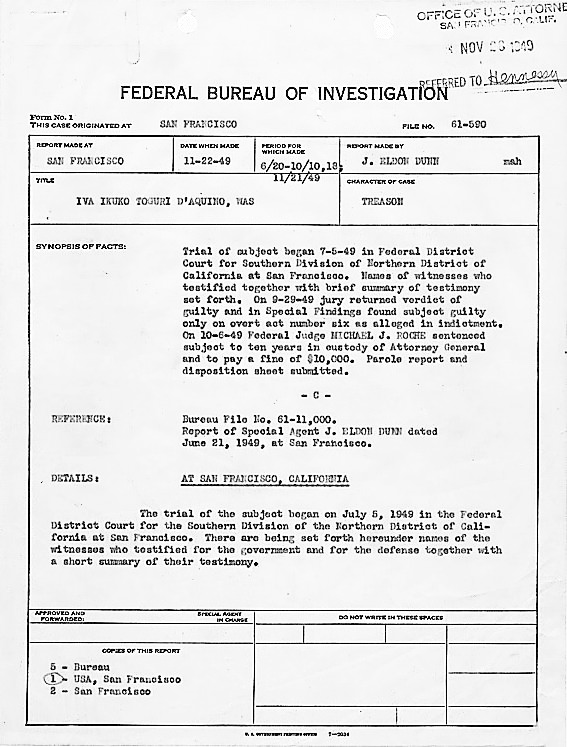

Tokyo Rose Trial: 1949

Defendant: Iva Ikuko Toguri ("Tokyo Rose")

Crime Charged: Treason

Chief Defense Lawyers: Wayne M. Collins, George Oishausen, and Theodore Tamba

Chief Prosecutors: Thomas DeWolfe, Frank J. Hennessy, John Hogan, and James Knapp

Judge: Michael J. Roche

Place: San Francisco, California

Dates of Trial: July 5-September 29, 1949

Verdict: Guilty

Sentence: 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine

SIGNIFICANCE: The Tokyo Rose trial was one of only seven American treason trials following World War II.

—————————————————————————————————

FBI Trial Synopsys

Iva Toguri D'Aquino, known as Tokyo Rose, is escorted from Federal Court by US Deputy Marshal in San Francisco, California

Iva Toguri listens to broadcast recordings

Iva Toguri and her attorney Wayne Collins

Iva Toguri after hearing the guilty verdict of the court

Prison

Iva was Prisoner 9380W in the Women's Federal Reformatory at Alderson, West Virginia, a small facility in the Alleghenies with an inmate population of three to five hundred, few of whom were vicious or hardened criminals. Most were moonshiners brought in from the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and the Carolinas for federal liquor tax law violations.

Although her official classification as a "notorious offender" -- and the reputation of the "Tokyo Rose" legend -- engendered some initial hostility, Iva was soon regarded as a model prisoner by the Alderson staff, always cheerful and helpful, keeping the floors of her cottage clean and shining.

The leather goods and bookends that she made in the prison handicrafts program won three 1st Prizes and one 2nd Prize at the 1952 West Virginia State Fair. Her IQ tested out at 130 on the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale.

Iva was also highly lauded for the quality and quantity of her work at the prison. She worked first as a supply clerk, then did a card study, then became an assistant to the medical aide, working her way up to X-ray operator, medical purchaser and finally laboratory assistant, where her duties included running the X-ray lab, taking EKGs and testing Basic Metabolism Rates (BMR). Her own BMR was 84, the highest she ever tested, which concerned the prison doctor so much that he put her on tranquilizers, to which she reacted badly. Her family visited her as often as possible and she played bridge with the other inmates, including Mildred Gillars, who was serving 10 to 30 years for treason for her "Axis Sally" radio propaganda broadcasts from Berlin. Iva continued to correspond with Felipe in Japan and her family in Chicago.

Iva’s official prison record speaks most eloquently for itself. On 17 June 1953, Iva received her one and only disciplinary action, a reprimand and loss of “meritorious good time” (MGT) for the month of June. Her offense? She extracted another inmate’s rotten tooth without authorization or supervision during the absence of the Dental Officer.

Finally after serving six years and two months she was released on parole to face another round of protest. As she walked out of the prison, she was handed a deportation notice ordering her back to Japan. Even so, she earned an early release after serving six years and two months, by virtue of 1,200 days of accumulated MGT, only to face yet another round of public protest. As she walked out of Alderson prison, on 28 January 1956, she was handed a deportation notice ordering her back to Japan.

Iva Toguri escorted to prison by US Deputy Marshal

Women's Federal Reformatory at Alderson, West Virginia

Reporters interview Iva Toguri upon her parole from prison (1956)

Life After Prison and Pardon

She reunited with her family, settled in Chicago and began working as an employee at her father business, but her reputation as “Tokyo Rose” continued to follow her. She was forced to fight off a deportation order from the U.S. government, and received no answer from repeated presidential pardon requests.

Iva's lawyer Wayne Collins took her into his home for the two years it took to fight the deportation order. Iva joined her family in Chicago and did her best to disappear, to put the past behind her. A few years later, former AP Japanese Bureau Chief Rex B. Gunn became the first journalist to speak out on Iva's behalf. Petitions for a Presidential pardon were filed with the Eisenhower administration in 1954, the Johnson administration in 1968, and the Nixon/Ford administration in 1976.

According to studies conducted in 1968, of the 94 men who were interviewed and who recalled listening to The Zero Hour while serving in the Pacific, 89% recognized it as propaganda, and less than 10% felt "demoralized" by it. 84% of the men listened because the program had "good entertainment," and one GI remarked, "Lots of us thought she was on our side all along."

CBS correspondent Bill Kurtis produced the 4 November 1969 broadcast of The Story of "Tokyo Rose" documentary for CBS in 1969. In that interview, Iva Toguri told Bill Kurtis:

"I suppose, if they found someone and got the job over with, they were all satisfied. It was Eeny, Meeny, Miney … and I was Moe.

"The trial? Well, it covered thirteen weeks and there was just a multitude of witnesses who appeared whom I’d never seen before, never heard of before and yet they professed to have known me. They testified that they saw the broadcasts, heard the broadcasts, which was impossible because the Allied POWs were under guard and they couldn’t have got into the studio. But they all testified that they heard me say these things and they saw me actually perform. So many witnesses were brought over here. I suppose, after the war, they were asked to come and given so much and three meals a day, a trip to the US, that a lot of people just jumped at the chance. It didn’t make any difference what sort of witness they would make."

When Wayne Collins died in 1974, his son, Wayne Collins Jr, took up the fight.

In 1976, investigative journalists found two key witnesses that admitted that they had been threatened and goaded into testifying against her. One of them said:

"She got a raw dead. She was railroaded into jail."

Around that same time, the foreman of her jury said that the judge in the case had pressed for a guilty verdict.

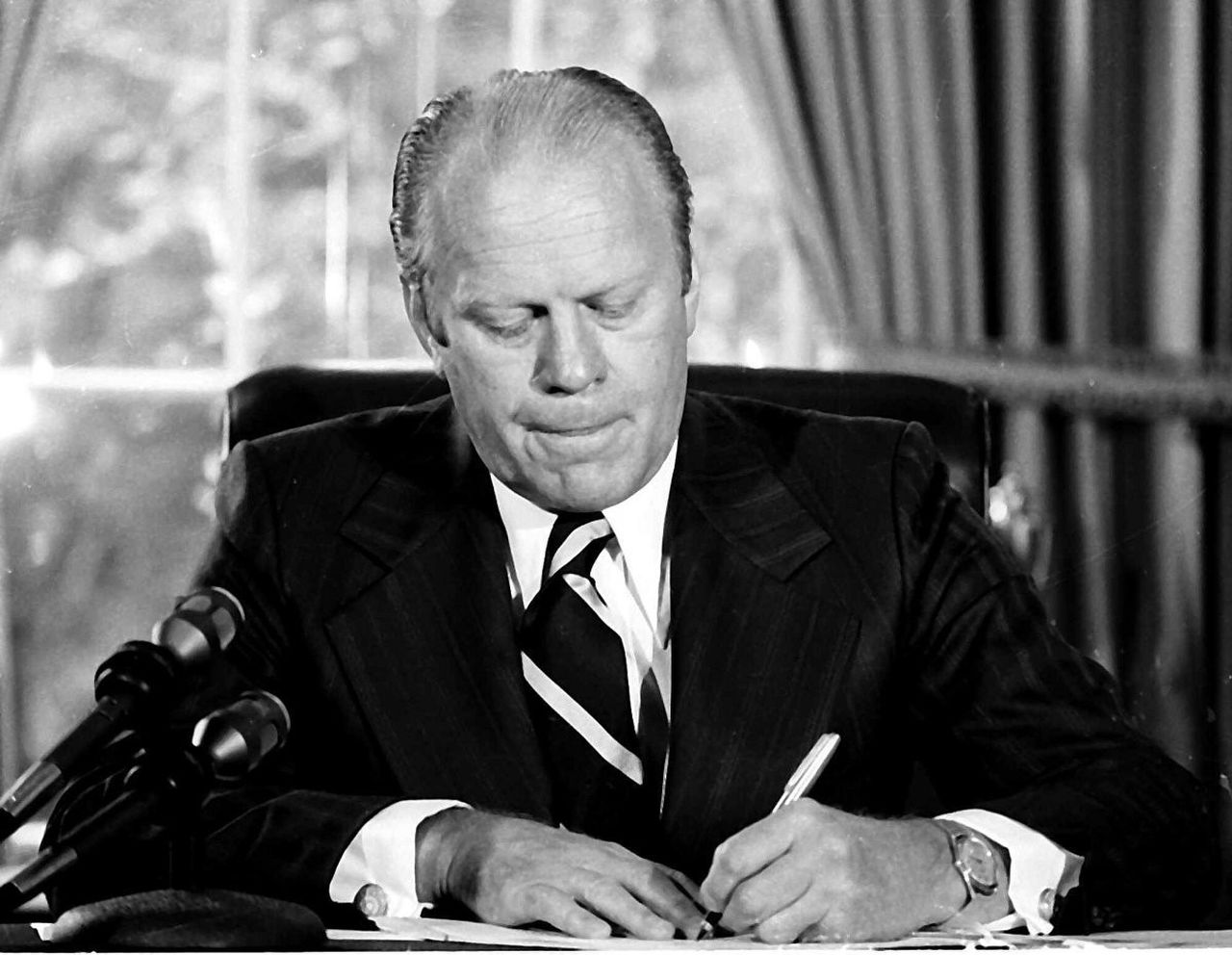

For only the second and so far the last public interview in the fifty years since the trial, Iva agreed to appear on "60 Minutes" in 1976, for what became the ground-breaking event leading to her pardon by President Gerald Ford. Morley Safer produced a segment for 60 Minutes that helped bring the pardon movement to public awareness.

U.S. President Gerald Ford finally pardoned Iva Toguri D'Aquino on 19 January 1977.

Iva Toguri reluctantly divorced Felipe D'Aquino a few years later, since she would never leave the U.S. again and he was forbidden entry as an undesirable alien, but she never stopped loving him. He died in Japan in November 1996, forty-three years after their forced separation and fifteen years after the divorce, but to Iva it was still like losing him all over again.

Iva Toguri's gift shop in Chicago at 851 W Belmont Ave (at Clark St.), a few blocks south of Wrigley Field. The 65-year-old business, J. Toguri, with roots back to World War II, was closed in 2013. Iva Toguri passed away in 2006.

Morley Safer produced a 60 Minutes interview with Iva Toguri (aka "Tokyo Rose") in 1976 after she had been granted a pardon by President Gerald Ford. [27:33]

This is the story of the woman who was put in jail for treason after the war, railroaded by a corrupt media and judicial system, and finally gets an opportunity to speak about these events many years after they had transpired. It is fascinating to hear hear story while being interviewed by a professional journalist. This is history in review and well worth watching.

Video from the Glenn Beck Show of November 9, 2013 entitled "Iva Toguri's Microphone After Nearly 70 Years – aka Tokyo Rose." [15:11]

This was the exact microphone that she used during her World War II radio broadcasts from Tokyo as either "Orphan Ann" or "Orphan Annie." From there, Beck tells the story of how he acquired Iva Toguri's microphone after nearly 70 years and then goes into some of the story behind the trial of "Tokyo Rose."

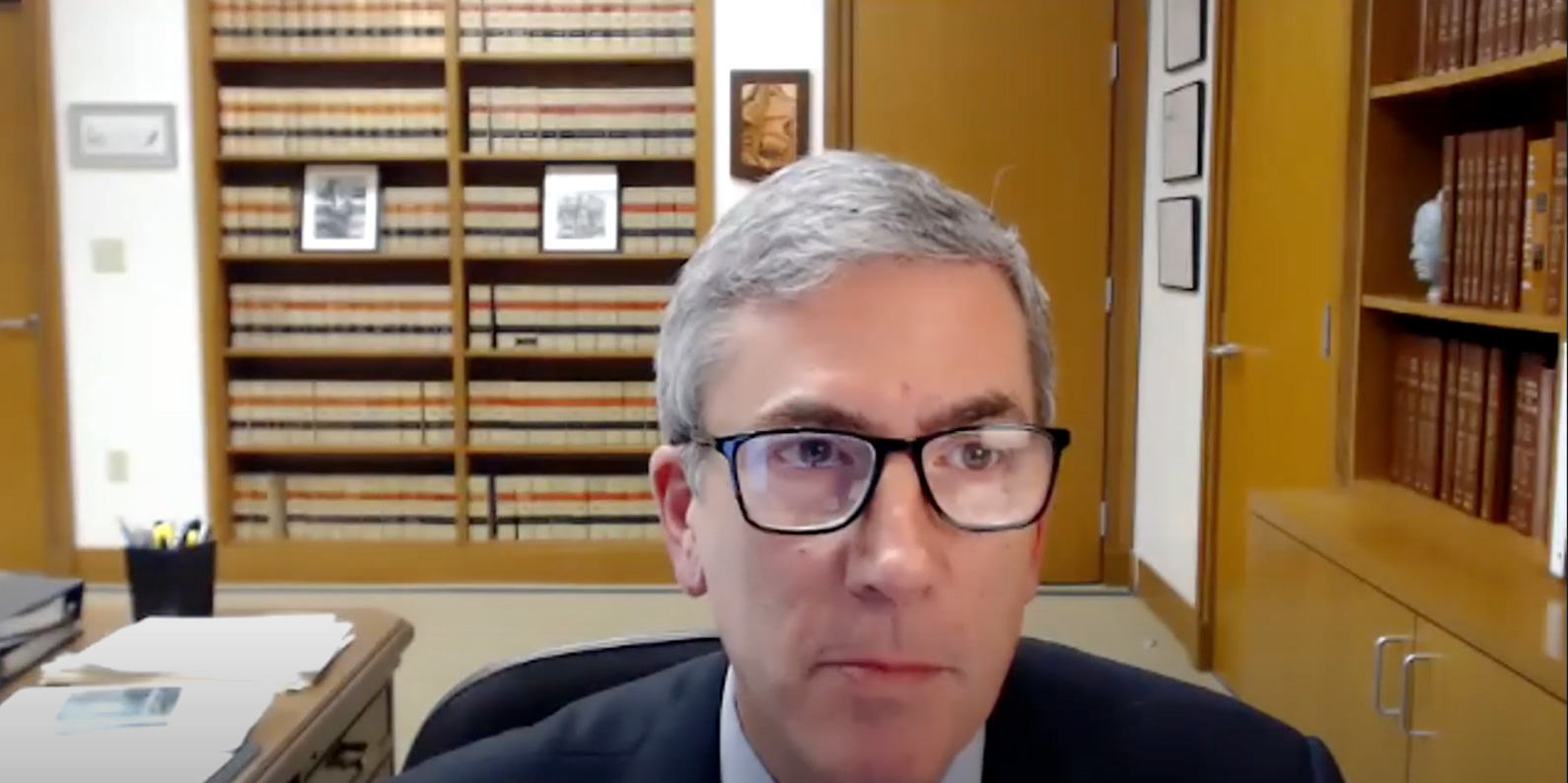

The Mistrial of Iva Toguri and the Myth of "Tokyo Rose" [1:19:12]

For those who would like to explore the flaws in the original trial of Iva Toguri, here is a virtual program presented by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California Historical Society on November 18, 2020, moderated by the Honorable Jon S. Tigar. The actual analysis and discussion starts at 10:58 and playback is set to skip ahead to that point in the video.

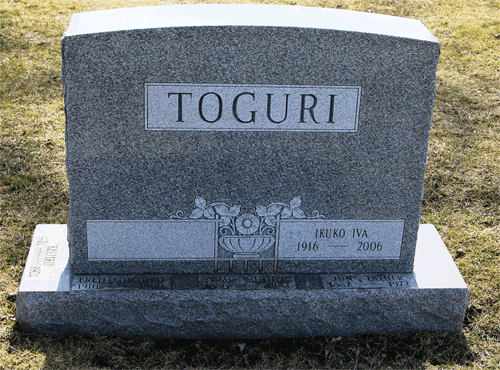

Death

Iva Toguri D'Aquino, died of natural causes at home in Chicago on 26 September 2006. She was 90. (See New York Times article.)

"You can either sit in a room and feel sorry for yourself or you can go outside and look ahead. I’ve tried to look ahead. … I try to forget the past and live with an eye to the future, trying to make a new life for myself while I forget the old one. … I believe in what I did. I have no regrets, and I don’t hate anyone for what happened."

Final resting place at Montrose Cemetery in Chicago, IL.

Iva Toguri D'Aquino in her later years

Source: Ed Rouse

www.psywarrior.com

Tokyo Rose Page