Operation Magic Carpet

Overview

Operation Magic Carpet was the post-World War II operation by the War Shipping Administration to repatriate over eight million American military personnel from the European, Pacific, and Asian theaters. Hundreds of Liberty ships, Victory ships, and troop transports began repatriating soldiers from Europe in June 1945. Beginning in October 1945, over 370 navy ships were used for repatriation duties in the Pacific. Warships, such as aircraft carriers, battleships, hospital ships, and large numbers of assault transports were used. The European phase of Operation Magic Carpet concluded in February 1946 while the Pacific phase continued until September 1946.

View of the hangar deck of the U.S. Navy escort carrier USS Salamaua (CVE-96) during a "Magic Carpet" run, bringing home U.S. servicemen from the Pacific War theater to the U.S. in late 1945.

Operation Magic Carpet, the code name given to the massive effort to bring Allied fighting men and women home from battlefields around the world, began in June 1945. However, by V-E Day it had been in the making for some time. Under the auspices of the War Shipping Administration, the program had been in development since 1943 as planners grasped the enormity of the task that would confront them once victory was won.

Planning

As early as mid-1943, the United States Army had recognized that, once victory was had, bringing the troops home would be a priority. More than 16 million Americans were in uniform; and more than eight million of them were scattered across all theaters of war worldwide. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall established committees to address the logistical problem.

The efforts to repatriate the newly demobilized soldiers involved as much military planning as many of the battles of the preceding war years.

Eventually organization of the operation was given to the War Shipping Administration (WSA). It understood the scale and complexity of the task and the need to bring servicemen and women home as quickly as possible. The operation also involved returning German and Italian POWs to Europe. Around half a million POWs were repatriated in the course of Operation Magic Carpet.

Service Rating Score

Eligibility for repatriation was determined by the Advanced Service Rating Score.

The Adjusted Service Rating Score was the system that the United States Army used at the end of World War II in Europe to determine which soldiers were eligible to be repatriated to the United States for discharge from military service as part of Operation Magic Carpet.

An enlisted man needed a score of eighty-five points to be considered for demobilization. The scores were determined as follows:

- Month in service = One point each

- Month in service overseas = One point each, in addition to month in service

- Combat award (Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Legion of Merit, Silver Star Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, Soldier's Medal, Bronze Star Medal, Air Medal, Purple Heart) or campaign participation star = Five points each

- Dependent child under eighteen years old = Twelve points each

Before the surrender of Japan, officers who may have had to serve again in combat were assessed not only on their ASR score but also on their efficiency and military specialities. Most high-scoring officers could have expected an early discharge after VE Day. The qualifying score was revised down to eighty points after VJ Day. In the coming months it would be lowered again.

A total of 29,204 servicemen returned aboard USS Saratoga, more than on any other individual ship.

Logistics

In December 1945, at the start of the operation, almost 8 million Allied military personnel were waiting to begin their journey back home. During the 14-months of Operation Magic Carpet, an average of 435,000 military personnel were being transported back every month. The record for a single ship was set by the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga which repatriated a total of 29,204 soldiers.

Conditions were crowded. Nobody cared. They were going home!

Europe

The Navy was excluded from the initial European sealift, as the Pacific War was far from over, and the task of returning the troops was the sole responsibility of the Army and Merchant Marine. The WSA ordered the immediate conversion of 300 Liberty and Victory cargo ships into transports. Adequate port and docking facilities were also serious considerations along with the transportation necessary to take the veterans to demobilization camps after they reached America's shores.

There were 3,059,000 service men and women in Europe, Africa and the Mediterranean on VE-Day. The first homeward-bound ships left Europe in late June 1945, and by November, the sealift was at its height. Whereas American shipping had averaged the delivery of 148,000 soldiers per month to the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during the wartime build-up, the post VE-Day rush homeward would average more than 435,000 GIs per month for the next 14 months.

In mid-October 1945 the United States Navy donated the newly commissioned carrier USS Lake Champlain – fitted with bunks for 3,300 troops – to the operation. She was joined in November by the battleship USS Washington. The European lift now included more than 400 vessels. Some would carry as few as 300 while the large liners often squeezed 15,000 aboard. One of the ocean liners, the British HMS Queen Mary, the U.S. obtained the use of in exchange for 10 smaller U.S. vessels. The WSA and the army also converted 29 troopships into special carriers for war brides, for the almost half a million European women who had married American servicemen. The Magic Carpet fleet also included 48 hospital ships; these transported more than half a million wounded.

Nor was this a one-way stream. Former Axis POWs had to be repatriated from Europe and Japan and occupation forces had to be dropped in Germany, China, Korea and Japan. Returned to Europe were more than 450,000 German prisoners of war, in addition to 53,000 Italian ex-POWs. Between May and September 1945, 1,417,850 were repatriated.

Between October 1945 to April 1946, another 3,323,395 were repatriated. By the end of February, the ETO phase of Magic Carpet was essentially completed.

Asia and the Pacific

With the surrender of Japan, the navy also began bringing home Sailors and Marines. Vice Admiral Forrest Sherman's Task Force 11 departed Tokyo Bay early in September 1945 with the battleships USS New Mexico, USS Idaho, USS Mississippi, and USS North Carolina, and two carriers plus a squadron of destroyers filled with homeward-bound servicemen. Stopping at Okinawa, they embarked thousands more Tenth United States Army troops.

The navy hastily converted many of its warships into temporary transports, including aircraft carriers, where three-to five-tiered bunks were installed on the hangar decks to provide accommodation for several thousand men in relative comfort. The navy fleet of 369 ships included 222 assault transports, 6 battleships, 18 cruisers, 57 aircraft carriers and 12 hospital ships.

By October 1945, Magic Carpet was operating worldwide with the Army, Navy and WSA pooling their resources to expedite the troop-lift. December 1945 became the peak month with almost 700,000 returning home from the Pacific. With the final arrival of 29 troop transports carrying more than 200,000 soldiers and sailors from the China-Burma-India theater in April 1946, Operation Magic Carpet came to its end. The last of the troops to return from the Pacific war zone (127,300) arrived home in September 1946.

Airlift

The army's Air Transport Command (ATC) and the navy's Naval Air Transport Service (NATS) were also involved in Magic Carpet operations, amassing millions of flying hours in transport and cargo aircraft, though the total number of personnel returned home by aircraft was tiny in comparison to the numbers carried by ship.

Get Them Home for Christmas!

In September 1945 there were 2,000,000 American army personnel eligible to be relieved of their wartime duties and waiting to be returned home. As the year wore on hopes were raised of getting the troops home in time to spend Christmas with their families. The task (sometimes referred to as Operation Santa Clause) was never going to be easy and was hindered further by heavy storms which delayed travel by sea.

Once the American troops returned to their homeland they faced further delays crossing the continent to reach their homes. Their initial destination was one of the many repatriation centres along the West Coast. Although not “home” these centres provided temporary accommodation while officials ensured that all the paperwork to release the service men and women from their duties was processed correctly. While it must have been hard to be so close to home yet still so far away, many were just glad to be back on American soil.

To make matters worse, there were traffic jams across the country as well as train delays of between 6 and 12 hours. In addition to the delays, there were simply not enough trains to accommodate all the soldiers trying to make their way back home.

On 24th December 1945 almost all the passengers (94%) travelling in trains from the west coast were recently released veterans. Those who did not make it back to their own homes were offered hospitality by locals living near the repatriation centres.

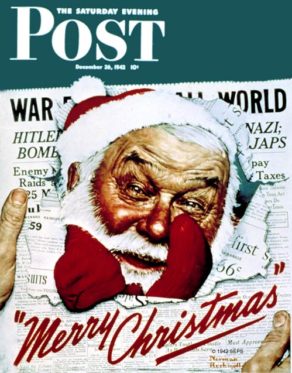

Santa's in the News, Norman Rockwell, December 26, 1942.

Kindness of Strangers

The soldiers were touched by the generosity of strangers who opened their homes to them, sharing their Christmas dinner. Others ate the Christmas dinner provided in the separation centres while others celebrated the holiday still on board the ships that had brought them, now docked in the harbour. Although they were still not back with their families, in the words of one returning soldier, just being back on American soil was the best Christmas present he could ask for.

Those attempting the journey home were also overwhelmed by the generosity and support shown to them by their fellow countrymen. There were impromptu parties thrown for them in towns where the trains had to make a stopover. There were stories of civilians giving up their own places on the trains so that the returning veterans could travel in their place.

Because trains were overcrowded and many soldiers were unable to get tickets, local truckers and taxi drivers stepped in, volunteering to take servicemen and women home even although it meant they would miss spending time with their own families at Christmas. A taxi driver from Los Angeles took a group of six veterans all the way to their home in Chicago – a journey of 2,000 miles – while another drove six veterans from L.A. to their homes in Manhattan, The Bronx, Pittsburgh, Long Island, Buffalo and New Hampshire. Both drivers accepted only the cost of the gas they had used for the journey as payment.

“This is the Christmas that a war-weary world has prayed for…” proclaimed President Truman at the National Tree lighting ceremony on Dec. 24, 1945 – and Americans did everything they could to give their servicemen and women the holiday they deserved.

The Final Phase

In total, there were over 8 million Allied soldiers waiting to be brought home from their stations in the European Asian and Pacific Areas and the operation to return them all took eighteen months to complete. The European phase of Operation was completed by February 1946, but it took until September 1946 to complete the final Pacific phase.

As a whole, it was a massive operation made possible by a great deal of careful planning and helped by the goodwill of civilians who appreciated the sacrifices the returning troops had made on their behalf.

Sources: Wikipedia and War History Online