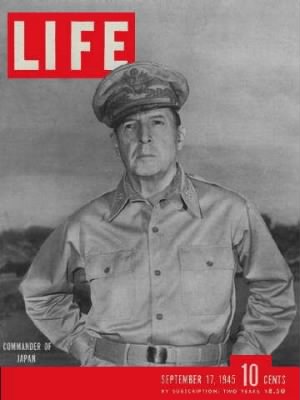

General Douglas MacArthur

A Brief Biography

"You couldn't shrug your shoulders at Douglas MacArthur," observes historian David McCullough. "There was nothing bland about him, nothing passive about him, nothing dull about him. There's no question about his patriotism, there's no question about his courage, and there's no question, it seems to me, about his importance as one of the protagonists of the 20th century."

Douglas MacArthur lived his entire life, from cradle to grave, in the United States Army. He spent his early years in remote sections of New Mexico, where his father, Arthur MacArthur Jr., commanded an infantry company charged with protecting settlers and railroad workers from the Indian "menace." As a teenager, Arthur had served with distinction in the Union Army, eventually earning the Congressional Medal of Honor for leading a courageous assault up Missionary Ridge in Tennessee. But he soon discovered that life in the post-Civil War U.S. Army held little of the glamour he knew during the war. These years were even harder for Douglas' mother, Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur, whose upbringing as a proper Southern lady had done little to prepare her for raising a family on dusty western outposts. But seen through a boy's eyes, life at a place like Ft. Selden, New Mexico, was heady stuff. "My first memory was the sound of bugles," Douglas MacArthur recalled in his "Reminiscences." "It was here I learned to ride and shoot even before I could read or write -- indeed, almost before I could walk or talk." Even more importantly, by watching his father and listening to his mother, he learned that a MacArthur is always in charge.

When Douglas was six, Captain MacArthur was assigned to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, where "Pinky," as his mother was known, could finally introduce him and his older brother Arthur to life back in "civilization." Three years later the family took another step in that direction when they moved to Washington, D.C., where Arthur took a post in the War Department. During these formative years, Douglas was able to spend time with his grandfather, Judge Arthur MacArthur, a man of considerable accomplishment and charm. As his grandfather entertained Washington's elite, Douglas learned another valuable lesson: a MacArthur is a scholar and a gentleman.

Douglas, who had always been an unremarkable student, first started to reveal his own intellectual gifts when his father was posted to San Antonio, Texas, in 1893. There he attended the West Texas Military Academy, thriving in an atmosphere which combined academics, religion, military discipline and Victorian social graces. By virtue of his excellent record there, his family's political connections and top scores on the qualifying exam, Douglas received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1898. Over the next four years, he would achieve one of the finest records in Academy history. General Arthur MacArthur -- back from the Philippines, where he had helped defeat the Spanish and served as military governor -- looked on proudly as his son graduated first in the class of 1903.

What became a lasting connection with the Philippines began with Douglas' first assignment out of West Point, when the young Lieutenant sailed to the islands to work with a corps of engineers. While on a surveying mission there, he recalled being "waylaid on a narrow jungle trail by two desperados, one on each side." MacArthur responded without hesitation. "Like all frontiersmen, I was expert with a pistol. I dropped them both dead in their tracks, but not before one had blazed at me with an antiquated rifle." Soon after this first brush with physical danger, MacArthur enjoyed excitement of a different kind, when he was assigned to accompany his father on an extended tour through Asia, where the General would review the military forces of eleven countries. The MacArthurs, Pinky included, were treated like royalty, and Douglas came away from the trip firmly convinced that America's future -- and his own -- lay in Asia.

One of Douglas's next assignments included service as an aide in Theodore Roosevelt's White House. But when he found himself in a tedious engineering assignment in Milwaukee in 1907, his performance dropped and he received a poor evaluation. To add to his confusion, he had fallen in love with a New York debutante named Fanniebelle, and his brilliant career prospects seemed to wane. But Douglas made amends in his next assignment, at the staff college at Leavenworth, and when his father died in 1912 he was transferred to the War Department in Washington, so that he could care for his mother. While there he was taken under the wing of Chief of Staff Leonard Wood, a protege of his father, and his career was again firmly on track. In 1915 MacArthur was promoted to major and the following year became the Army's first public relations officer, performing so well that he is largely credited with selling the American people on the Selective Service Act of 1917, as the country moved ever closer to joining the war in Europe.

Even though his record to that point had been excellent, the First World War gave Douglas MacArthur his first real measure of fame. Quickly promoted to brigadier general, he helped lead the Rainbow Division -- which he had helped create out of National Guard units before the war -- through the thick of the fighting in France. With a flamboyant, romantic style matched only by real feats of courage on the battlefield, MacArthur became the most decorated American soldier of the war.

While his peers were demoted to their pre-war ranks, MacArthur kept his through a plum new assignment as Superintendent of West Point. Although he antagonized many of the old guard, MacArthur made good on his mandate to drag the moribund Academy into the 20th century, enabling it to produce officers fit to lead the country in the type of modern war he had just experienced first hand. He also managed to get married -- to Louise Cromwell Brooks, a vivacious flapper and heiress very different from her spit-and-polish second husband. A minor scandal erupted when Chief of Staff John J. Pershing -- with whom Louise had had an affair during the war -- shipped MacArthur from West Point to a makeshift assignment in the Philippines. Although disappointed, MacArthur was glad to be back in his beloved islands; Louise, used to the glamorous society of cities like New York and Paris, was not pleased. Even after their return to the States in 1925, the marriage continued to deteriorate. Louise filed for divorce in 1928. Once again, MacArthur found solace in the Philippines, where he took command of the Army's Philippine Department and renewed a friendship with the island's leading politician, Manuel Quezon, whom he had known since 1903.

Although he and Quezon failed in their bid to have MacArthur named governor of the Philippines, President Hoover helped take the sting out of it by naming MacArthur to the Army's top job, Chief of Staff, in 1930. But the early '30s were a trying time to be Chief, when the Great Depression made Americans deaf to MacArthur's warnings about the rising tide of world fascism. Despite his able leadership, the Army fell to all-time lows in strength under his watch. This, along with the damage to his reputation from the Bonus March of 1932, when he very visibly led army troops in routing impoverished World War I vets from the capital, made MacArthur receptive to other opportunities. Once again, he was drawn to the Philippines. In 1935, his old friend Quezon, President of the newly created Philippine Commonwealth, invited him to return to Manila as head of a U.S. military mission charged with preparing the islands for full independence in 1946.

The next few years were among the happiest in MacArthur's life. On his way to Manila, he met and fell in love with 37-year-old Jean Marie Faircloth from Murfreesboro, Tennessee. When Pinky died shortly after their arrival in Manila, Jean helped fill the void, and her devotion would remain a source of strength for the rest of his life. After the birth of their son, Arthur MacArthur IV, the 58-year-old general proved a doting father. But their blissful life in Manila was slowly overshadowed by the growing threat posed by an expansionist Japan. MacArthur, despite the able assistance of top aide Dwight Eisenhower, would not have enough time or money to build a force capable of resisting the Japanese. When war finally came with the blow at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines was doomed: MacArthur's air force was quickly destroyed, his army shredded, and by January his forces had retreated to the Bataan peninsula, where they struggled to survive. From his command post on the island of Corregidor at the mouth of Manila Bay, MacArthur watched his world fall apart.

But despite MacArthur's poor showing in the Philippines, President Roosevelt knew he couldn't let America's most famous general fall to the enemy, and ordered him to withdraw to Australia. Although it ran counter to his notion of a soldier's duty, MacArthur left his men facing sure destruction, comforted only by the belief that he might lead an army back to rescue them. For the next three years, the world watched as his personal quest -- "I shall return" -- became almost synonymous with the war in the Pacific. Although MacArthur's path through the dense jungles of New Guinea was hardly imagined in the initial war plans, his singleminded drive and resourcefulness made it one of the two prongs in the Allied drive to roll back the Japanese. Simultaneously fighting a two front war -- one with the Japanese, the other with the U.S. Navy, who understandably saw the Pacific as theirs -- MacArthur slowly gained momentum. In October of 1944 the world watched as he dramatically waded ashore at Leyte, and in the following months liberated the rest of the Philippines. On September 2, 1945, he presided over the Japanese surrender on board the "U.S.S. Missouri," bringing an end to World War II.

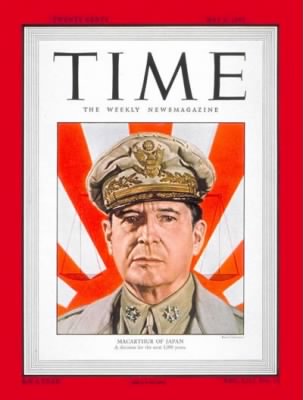

His place as a leading figure of the 20th century already secure, MacArthur may have made his greatest contribution to history in the next five and a half years, as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan. While initiating some policies and merely implementing others, by force of personality MacArthur became synonymous with the highly successful occupation. His GHQ staff helped a devastated Japan rebuild itself, institute a democratic government, and chart a course that has made it one of the world's leading industrial powers. Yet by the late 1940s, MacArthur was increasingly bypassed by Washington, and it seemed his remarkable career might be over.

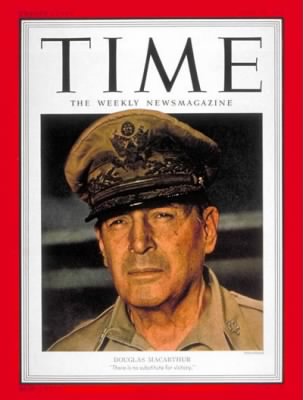

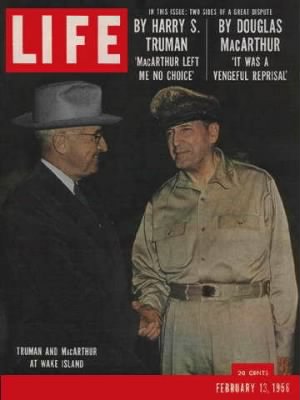

But in June of 1950, the sudden outbreak of the Korean War -- "Mars' last gift to an old warrior" -- thrust MacArthur back into the limelight. Placed in command of an American-led coalition of United Nations forces, MacArthur reversed the dire military situation in the early months of the war with a brillian amphibious assault behind North Korean lines at the Port of Inchon. But within weeks of this great triumph he and Washington miscalculated badly. MacArthur's approach to the Chinese border triggered the entry of Mao's Communist Chinese, and as 1951 dawned, they faced what he called "an entirely new war." Although the able leadership of General Matthew B. Ridgway stabilized the military situation near the prewar boundary at the 38th parallel, MacArthur's months of public and private bickering with the Truman administration soon came to a head. On April 11, 1951, the President relieved General MacArthur, triggering a firestorm of protest over our strategy not only in Korea, but in the Cold War as a whole. As the last great general of World War II to come home, MacArthur received a hero's welcome. Despite his dramatic televised address to a joint session of Congress, however, the issue died quickly, and with it any hopes MacArthur had of reaching the White House in 1952.

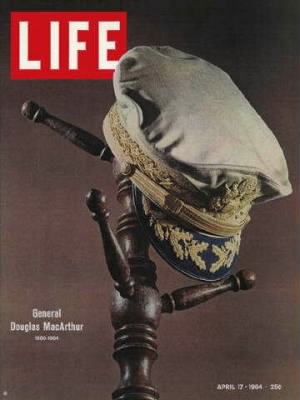

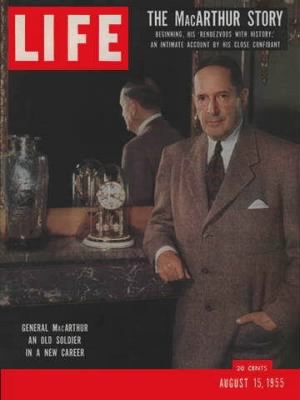

True to his word, the old soldier "faded away" from the public eye, living quietly in New York until his death in 1964. While it's questionable whether his storied life ever brought him complete satisfaction, one thing is clear: Douglas MacArthur had more than fulfilled his self-imposed destiny of becoming one of history's great men.

Source: fold3.com