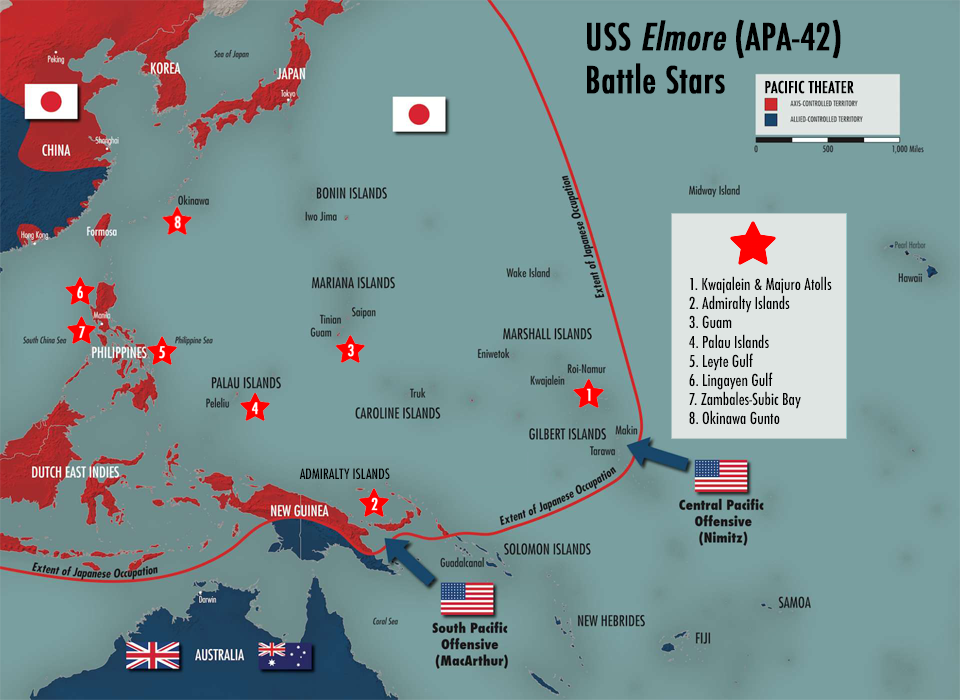

Battle Stars

USS Elmore (APA-42) earned eight battle stars in the Pacific campaign during World War II.

Marshall Islands Operation

Capture and occupation of Kwajalein and Majuro Atolls, 31 January to 8 February 1944.

Battle of Kwajalein

Introduction

In late January 1944, a combined force of U.S. Marine and Army troops launched an amphibious assault on three islets in the Kwajalein Atoll, a ring-shaped coral formation in the Marshall Islands where the Japanese had established their outermost defensive perimeter in World War II. Kwajalein Island and the nearby islets of Roi and Namur were the first of the Marshall Islands to be captured by U.S. troops, and would allow the Pacific Fleet to advance its planned assault on the islands and its drive towards the Philippines and the Japanese home islands.

The Marshall Islands and The U.S. “Island-Hopping” Strategy

The peace settlement that ended the First World War gave Japan a mandate over the Marshall Islands in the western Pacific Ocean. Kwajalein, in the Ralik (western) chain of the Marshalls, was the world’s largest coral atoll, numbering some 90 islets (with a total land area of six square miles) surrounding a 655-square-mile lagoon. By the beginning of World War II, Japan had established the Marshalls as an integral part of its defensive perimeter, and the islands became an important target for the Allies in their wartime planning.

The "island-hopping" strategy of 1943 represented a compromise between two major U.S. commanders: General Douglas MacArthur, who pushed for the immediate recapture of the Philippines (taken by the Japanese in 1942) and Nimitz, who advocated bypassing the Philippines for weaker-held positions in the Pacific.

In 1943, after Japan had scored victory after victory during the first months of war in the Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz proposed an aggressive counteroffensive strategy consisting of a series of amphibious assaults on selected Japanese-held islands on the way to the Philippines and on towards Japan itself. The strategy, known as “island-hopping” or “leapfrogging,” turned on the idea that merely isolating some Japanese forces on their islands–letting them “wither on the vine”–would be as effective as destroying them through a direct attack, and far less costly to Allied forces.

From Tarawa to Kwajalein

The bloody conquest of Tarawa, a small atoll in the Gilbert Islands of the central Pacific, in November 1943 was a crucial precursor to the Allied campaign in the Marshall Islands. The 5,000 Japanese troops garrisoned on Tarawa mounted a ferocious resistance, killing more than 1,000 U.S. Marines and wounding another 2,100. Nearly all of the Japanese troops on Tarawa perished, in a striking example of the never-surrender attitude that would characterize the entire Japanese war effort.

Between Tarawa and Luzon, the main island of the Philippines, were 2,000 miles of sea, plus more than a thousand scattered atolls, many of them fortified with Japanese troops. The lessons of “Terrible Tarawa” (as the Marines dubbed it) helped the Allies prepare for the hard fighting that would characterize the central Pacific campaign. Moreover, because neither the Japanese fleet nor any land-based aircraft from other islands had interfered, Nimitz concluded it would be safe to skip other Marshall Island garrisons and proceed to the westernmost atolls in the chain: Kwajalein and Eniwetok.

Attack on Kwajalein, Roi and Namur

On January 30, 1944, after a massive air and naval bombardment lasting some two months, a U.S. Marine and Army amphibious assault force of 85,000 men and some 300 warships) approached the Marshall Islands. On February 1, the 7th Infantry (Army) Division landed on Kwajalein Island, while the 4th Marine Division landed on the twin islands of Roi and Namur, 45 miles to the north. A single Marine regiment captured Roi on that first day, while Namur fell by noon of the second day. The battle for Kwajalein would prove more difficult, as the 7th Infantry pounded the Japanese garrison there for three days until the island was declared secure on February 4.

Though greatly outnumbered from the start (by more than 40,000 on Kwajalein) the Japanese chose to fight until the bitter end. Japanese casualties on Roi and Namur numbered more than 3,500 killed and around 200 captured, with less than 200 Marines killed and some 500 more wounded. On Kwajalein, close to 5,000 Japanese defenders were killed and only a handful captured; the 7th Infantry counted 177 soldiers killed and 1,000 wounded.

Effects of U.S. Victory

While not an easy victory for the Allies, the capture of Kwajalein was accomplished ahead of Nimitz’s expectations, allowing him to advance by 60 days the planned attack on Eniwetok, 400 miles northwest of Kwajalein. An assault on Truk – a forward anchorage of the Japanese fleet – destroyed 275 Japanese aircraft and sank nearly 40 ships, and Eniwetok fell by February 21, after five days of fighting.

Their success in the Marshalls gave U.S. forces a major anchorage point and staging area from which to continue their amphibious operations in the central Pacific, as they opened the way to the Mariana Islands, including Saipan and Guam. In addition, the victories intensified the isolation of those Japanese island outposts that had been skipped in the Allied island-hopping campaign, including Wake Island, one of the first islands Japan had captured in the beginning stages of the war.

Source: History.com, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/battle-of-kwajalein

Bismarck Archipelago Operation

Admiralty Islands landings, 11 to 12 April 1944.

Admiralty Islands Landings

Introduction

The invasion of the Admiralty Islands (29 February-25 March 1944) was a major step in the isolation of the powerful Japanese base at Rabaul and saw forces from the US calvary capture the main islands in a series of battles that lasted for one month. The conquest of the Admiralty Islands helped complete the isolation of Rabaul by giving the Allies control of the western approaches to New Britain, as well as a useful site for airfields and control of the massive Seeadler Harbor.

Allied Strategy

The Admiralty Islands sit at the north-west corner of the Bismarck Sea, west of the Bismarck Archipelago (New Britain and New Ireland) and north of New Guinea. Allied control of the islands would thus help further isolate Rabaul, at the northern tip of New Britain, as well as providing bases for the Allied advance along the north coast of New Guinea. A further bonus would be control of the massive Seeadler Harbor, 20 miles long and 6 miles wide, a harbor capable of sheltering an entire fleet.

Japanese Strategy

The Japanese had recognized the importance of the Admiralty Islands. They were defended by 4,300 men, commanded by Colonel Yoshio Ezaki. They had also built an airfield on the largest island, Manus, and on nearby Los Negros. When the Americans attacked they would be outnumbered, but Ezaki expected the attack to come from Seeadler Harbor and so his defenses were all facing in, towards the harbor.

The Admiralty Islands had been an American target for some time, and the invasion was originally timetabled for April 1944. Early in 1944 aircrews from the Fifth Air Force reported that there was no Japanese activity on the islands. In addition, MacArthur was impatient to speed up his advance towards the Philippines. He decided to push the invasion forwards to late February 1944, but also realized that the aerial reconnaissance might be inaccurate. He decided to make the original landings a 'reconnaissance in force' and to accompany the task force in person so he could decide if the islands could be held or not.

The decision to invade was made on 24 February, with D-Day set for 29 February. Los Negros would be the first target, and the landing would be carried out by 1,000 men from the 1st Cavalry Division (Dismounted). A reserve of 1,500 men was also available. The landings would take place at Hyane Bay, on the east, ocean-facing, coast of Los Negros.

Geographical Significance

The Admiralty Islands contains eighteen main islands. The largest island, by far, is Manus. The island is about 100km/ 60 miles from west to east and 30km/ 18 miles from north to south. At the eastern tip of Manus is Los Negros, the third biggest of the islands. This island takes the shape of a horseshoe, curving around to the north then to the west. A series of small islands then run west from the north-western tip of Los Negros, running parallel to the north-eastern coast of Manus. The area inside this line of islands is Seeadler Harbor.

Allied Landings

On 27 February MacArthur boarded the USS Phoenix, the flagship of the invasion forces. On the same day a force of six scouts landed on Los Negros. They landed safely but found that the island was 'lousy' with Japanese troops. The news reached MacArthur at sea on 28 February, but he decided to press away with the invasion anyway. On the morning of 29 February the 1st Cavalry landed on Los Negros. The Japanese were caught entirely out of position, and the Americans quickly established a beachhead. That afternoon MacArthur paid a two hour visit to the island, and decided that his men should stay. He then left, taking most of the naval support force with him.

That night the Japanese launched an attack on the beachhead, but the Americans held their ground. In some areas the Japanese did manage to get inside the perimeter, and on the following morning the area had to be re-secured. Sixty-six Japanese troops were killed within the main perimeter.

Two days later reinforcements arrived, just in time to help repulse a second major Japanese attack on the night of 3-4 March. This was a more serious attack, and the Americans lost 61 dead while fighting it off. Japanese losses were much heavier, with 750 dead around the perimeter. This was the last major Japanese attack on Los Negros. The last major fighting came on 21-25 March, when the Japanese were forced out of their last organized defenses, on a ridge near Papitalai

Manus Island was the next target. The Manus task force entered Seeadler Bay on 9 March and began by occupying the islands that ran west from the northern end of Los Negros, parallel to Manus. The Japanese put up unexpectedly fierce resistance on Hauwei, but the island was secured on 12 March.

On 15 March the Americans landed at Lugos Mission, west of their main target at Lorengau. Lorengau airfield fell on 17 March, and the town fell soon afterwards. The hardest fighting came when the Americans began to advance south from Lorengau towards Rossum. This battle lasted from 19-25 March and ended organized Japanese resistance in the Admiralty Islands. The campaign officially came to an end on 18 May 1944, but by then the only Japanese left were isolated bands of stragglers.

Effects of U.S. Victory

The two battles cost the Americans 326 dead and 1,200 wounded. The Japanese lost 3,280 dead.

On New Guinea, the fall of the Admiralty Islands convinced General Adachi that he could no longer hold onto his base at Madang. He ordered his men to march west to Hansa Bay and Wewak, where he expected the next American blow to fall. Allied trooped made an unopposed entry into Madang on 24 April, two days after they had leapfrogged Adachi yet again, landing at Aitape and Hollandia, half way along the north coast of New Guinea.

The Admiralty Islands also became an important American base. Seeadler Harbor was a very useful naval base. In addition, a PT base was built at the northern tip of Los Negros, with a 8,000ft airstrip nearby and a 7,000ft airstrip was completed at Momote, near the original landing point at Hyane Harbor.

Source: Rickard, J (5 May 2015), Invasion of the Admiralty Islands, 25 February-25 March 1944

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/campaign_admiralty_islands.html

Marianas Operation

Capture and occupation of Guam, 21 to 25 July 1944.

Battle of Guam

Introduction

The battle of Guam (21 July-9 August 1944) saw the Americans reconquer an island that had been in their hands before the war after three weeks of fighting, completing the conquest of the Mariana Islands.

Allied Strategy

Guam was the southern island in the Marianas group. Like Saipan and Tinian, it offered several locations for B-29 airfields, but unlike those islands it also had an excellent protected anchorage that could be used by the US fleet. The island had been in American hands since the Spanish-American War, but it had fallen to the Japanese on 10 December 1941, after three hours of fighting, and had been in their hands ever since.

The original plan had been to invade Guam on 18 June, three days after the invasion of Saipan. However early on 16 June Admiral Spruance cancelled that decision, as a result of the discovery of a massive Japanese naval force heading his way. The invasion of Guam was postponed, and the fleet prepared to fight a major battle. The resulting Battle of the Philippine Sea (19-20 June 1944) was a crushing defeat for the Japanese, effectively destroying the IJN's naval aviation branch. The invasion was then further postponed when the main reserve force for the invasion had to be committed on Saipan. The new reserve force, the 77th Division, had to move up from Hawaii.

The delay meant that Guam was subjected to the longest pre-invasion naval bombardment of the Pacific War, lasting from mid-June, when the US fleet first appeared off the islands, to the invasion, well over a month.

Under the new plan Guam would be attacked first, with the invasion of Tinian starting three days later.

The island was protected by natural barriers. There were cliffs along much of the shore, and reefs blocking the approaches. The northern half of the island wasn't suitable for attack. The best landing points were in the south-west, south of the Orote Peninsula and north of the Piti naval station, north of the Peninsula. The island was long and narrow, with the Orote Peninsula the only major one. The southern half of the island is more rugged than the north, with a line of mountains around the southern half of the west coast. Apra Harbour, the good anchorage, was sheltered by the Orote Peninsula, while the capital city of Agana was further to the north-east along the coast.

Japanese Strategy

Guam was defended by 19,000 Japanese troops under General Takashina Takeshi. There were two operational airfields on the island at the time of the invasion, one on the Orote Peninsula on the west. Takashina realized that the invasion would almost certainly come in the south-west and eight of his eleven infantry battalions were posted in that area and the other three moved slowly closer to that area as the bombardment continued.

Allied Landings

The invasion of Guam was carried out by the newly formed 3rd Amphibious Corps (General Roy Gieger). Three forces were involved, all of which were to land on the western coast. On the left the 3rd Marine Division (General Allen Turnage) landed north of Apra Harbor. On the right the 77th Infantry Division (General Andrew Bruce) and the 1st Brigade (General Lemuel Sheperd) landed south of Apra Harbor. The two landing zones were five miles apart, and it would take four days for the two forces to join up.

The invasion began one minute ahead of schedule when the 3rd Marines landed at Asan Beach, on the American left, at 0829. After a day of heavy fighting that coast the Marines 105 dead, 536 wounded and 56 missing, the Marines had established a beachhead that was 4000 yards wide and a mile dead in most places. That night there was a disorganized Japanese counterattack, but nothing like the massive banzai charge that had been expected.

On the right the 1st Marine Brigade ran into heavy Japanese fire while approaching Agat beach, losing 350 men during the day. By the end of the day the Marines had established a food hold 4,500 yards wide and 2,000 yards deep. The major Japanese counterattack of the night came on this front, where there were three large attacks between 0230 and 0400. All three were repulsed, and as was so often the case these wasteful counterattacks achieved nothing apart from weakening the defenders.

The two beachheads remained separate for another four days, fighting largely separate battles.

On the right the 1st Brigade captured the Alifan ridgeline and established a strong right flank. One regiment from the 77th Division took over on the left, allowing the rest of the marine brigade to wheel right and advance north. They were ready to attack the Orote peninsula by 26 July.

On the left the 3rd Division had to capture a series of mountainous ridges before they reached more open ground on the Fonte Plateau. On their right they pushed south towards a junction with the 1st Brigade, leaving their lines dangerously stretched. General Takashina realised that this gave him a chance, and on the night of 25-26 July he committed seven battalions to a determined counterattack. This time the banzai attack came perilously close to success, with Japanese troops breaking into the American positions and the battle descending into a series of skirmishes scattered around the beachhead. Even so US firepower eventually won the battle, and when the fighting finished on the following day the Japanese had lost 3,500 dead (including 95% of the officers involved in the attack), the Americans 166 dead, 645 wounded and 34 missing. On the same night the Japanese troops trapped on the Orote Peninsula carried out an equally costly, but less effective attack. In one night the Japanese had thrown away a large part of their strength.

The surviving Japanese troops made the US advance as difficult as possible. It took four days for the 1st Brigade to capture the Orote Peninsula, which fell on 29 July. By now the Japanese had evacuated the southern half of the island. The Americans concentrated on taking the high ground in front of their beachheads and made secure contact between them on 28 July. They then turned north, with the 3rd Marines on the left and the 77thj Infantry on the right. Once again, the advance north was hard fought, and fairly costly, although not as bad as they might have been if the Japanese hadn't wasted so much strength on the night of 25-26 July. On the right the 77th captured the final Japanese strong point at Mount Santa Roas, while on the left the Marines fought their way to the north coast.

Effects of U.S. Victory

The advancing troops finally reached the northern end of the island on 10 August, and the island was declared to be secure. Even so Japanese troops continued to offer resistance for some time to come, and the last two didn’t surrender until 1960! The fall of Guam ended the major fighting in the Marianas and left the islands firmly in American hands. On Guam they had lost 1,744 dead and 5,970 wounded, while the Japanese had lost over 18,000 dead and 1,250 prisoners. The Americans were now free to use Guam as a naval and air base, and strike deep into the Japanese Empire and even reach the home islands.

Source: Source: Rickard, J (27 February 2018), Battle of Guam, 21 July-9 August 1944,

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_guam_1944.html

Western Caroline Islands Operation

Capture and occupation of southern Palau Islands, 6 September to 14 October 1944.

- Beach Purple - was situated along the southeast coast of the island and its major advantage was that it had a very narrow reef and one area that the landing craft would be able to actually come right up to the beach. The Japanese also thought this was a strong candidate for a landing and so placed substantial defences on it. There was also a mangrove swamp just inland that left a narrow strip of dry land to act as a causeway. This would be excellent defensive terrain and so Purple was ultimately rejected.

- Beach Scarlett - this was situated on the southern tip of the island and quickly rejected as a landing there in combination with another beach would increase the risk of casualties from friendly fire.

- Beach Amber - this was situated along the northwest coast of the island and had the disadvantages of having the widest part of the reef, would be under enfilade fire from nearby Ngesebus Island and was very close to some high ground which would dominate the beach if not taken quickly. This was also rejected.

- Beaches White and Orange - these provided an opportunity to drive eastwards across the island straight towards the airfield. These were the beaches selected.

Battle of the Palau Islands

Introduction

By 1944, the Japanese, while being far from defeated, were well and truly on the defensive. In Southeast Asia, British and Commonwealth forces had halted the Japanese offensive towards Kohima and Imphal and begun an offensive of their own which was pushing the Japanese back into central Burma. In the Pacific, the Americans had their two-prong drive well underway with the securing of Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands) and Tarawa (Gilbert Islands), followed up with the landings on Bougainville (Solomon Islands) and New Britain and the Admiralty Islands in 1943 and on Luzon (Philippines), Guam, Tinian and Saipan (Mariana Islands) in 1944, as well as continued fighting in New Guinea. As 1944 progressed, the Americans started to look towards securing targets much closer to the Japanese home base in order to have staging areas to prepare for their final attack on Japan, eventually codenamed Operation Downfall. These were likely to include Iwo Jima, Okinawa and Formosa, all of which had significant garrisons on them, MacArthur favoring the Formosa / China route, while Nimitz favored the Iwo Jima / Okinawa (Ryukus Islands) one.

The Palau Islands

The Palau Islands lie in an archipelago that stretches for over a hundred miles in a line running roughly from the northeast to southwest, starting with the largest island of Babelthuap and then continuing with Koror, Arakabesan Island, Urukthapel, Eil Malk, Ngemelis Island, Ngeregong Island, Garakayo Island, Ngesebus-Kongauru Island, Peleliu and finally Angaur. Peleliu is just over twenty square miles in size, and has a similar shape to that of a lobster claw. The southern end of the island is flat and open (well suited to the construction of an airfield) while the centre is dominated by the Umurbrogol Mountain that is, in actual fact, a series of limestone coral ridges, much of which is blanketed by thick jungle. Spanish missionaries discovered the islands in 1712 (although some claim that Spanish explorers under the Portuguese navigator Ruy Lopez de Villalobos chanced upon the island in 1543) and while the Spanish never really developed the islands, they were sold to Germany in 1899 after its defeat in the Spanish-American War. The Germans started to exploit the extensive phosphate reserves, particularly on Angaur, but their tenancy was short-lived as the Japanese declared war on Germany on 14 August 1914 and seized their Pacific possessions, including the Palau islands by the South Seas Squadron under Rear Admiral Tatsuo Matsumara on 4 October 1914. The League of Nations awarded the mandates to Japan in 1920, despite opposition from the United States, and a civil government (South Sea Bureau) was installed in 1922 with the South Sea Defense Force created to defend the mandate. Between the wars, Japan established a major presence on the Palau Islands that was somewhat shrouded in secrecy - it was on Koror that Lt Col Earl (Pete) Ellis, USMC died in mysterious circumstances in 1922 while touring the Pacific (he was in fact spying for the US Government). With the withdrawal of Japan from the League of Nations in 1935, the islands were closed to Westerners and the military facilities expanded to include airfields, seaplane bases and some coastal defenses. The outbreak of war in 1941 soon saw the importance of the Palau Islands grow, as it soon became a forward supply, training and staging point for the Armed Forces.

The Americans Prepare

The next stage in the Central Pacific campaign under Admiral Chester W Nimitz was seen as supporting General Douglas MacArthur's drive to retake the Philippines as quickly as possible, something he managed to convince both Admiral Nimitz and President Franklin D Roosevelt of, during their meeting in Honolulu in July 1944. He managed to secure the loan (again) of the 1st Marine Division as he had done in the Solomons campaign. The 1st Marine Division had already received a warning order in May 1944 to participate in Operation Stalemate. This plan saw the 1st Marine Division with the 81st Infantry Division (under III Amphibious Corps) assault Peleliu and Angaur (also sometimes spelt Anguar), alongside the 7th and 77th Infantry Divisions (under XXIV Corps) that would land on Babelthuap, all part of the Palau Island group. The 27th Infantry Division would remain in reserve on New Caledonia and the target date was set as 8 September 1944.

The delays in securing the Marianas had three immediate impacts upon the Peleliu operation in that it firstly, delayed the arrival of the new III Amphibious Corps commander, Major General Roy S Geiger until planning (undertaken by a temporary staff headed by Major General Julian Smith commanding Task Force 36, called X-Ray Provisional Amphibious Corps) was at quite an advanced stage and any major changes would be difficult to implement. Secondly, it caused major friction between the Army and the Marine Corps as Lieutenant General Holland ("Howlin' Mad") Smith had relieved Major General Ralph C Smith of his command of the 27th Infantry Division for 'defective performance'. This was to have serious repercussions all the way back to Washington DC and on the Peleliu operation, although the two formation commanders would actually work very well together. Thirdly, it continued to tie up troops, resources and shipping (particularly the III Amphibious Corps and 77th Infantry Division on Guam and the 27th Infantry Division on Saipan). Additionally, intelligence (including the capture of the 31st Army files and a Japanese Intelligence Officer on Saipan) revealed that Babelthuap had only marginal utility in regard to the potential expansion of the airfield facilities there and had a large Japanese garrison, while Peleliu already had an excellent operational airfield that once in American hands, could neutralize the northern one. So the planning was altered and the target date (for the first phase) changed to 15 September 1944, the same day as MacArthur's forces would take Morotai. The new plan would be known as Operation Stalemate II, the first phase of which would involve the III Amphibious Corps (still the 1st Marine and 81st Infantry Divisions) assaulting Peleliu and Angaur. The second phase would see XXIV Corps (now consisting of the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions) attacking the atolls of Yap and Ulithi on October 8th, while the 77th Infantry Division would become the operation's floating reserve and the 5th Marine Division acting as a general reserve on Hawaii. The two phases would be supported by the US Navy's Western Pacific Task Force from the Third Fleet. The Covering Forces and Special Groups (Task Force 30) would remain directly under Halsey, the Third Amphibious Force (Task Force 31) was divided into the Western Attack Force (Task Force 32) bound for Peleliu and Angaur under Rear Admiral George H Fort and the Eastern Attack Force (Task Force 33) bound for Yap and Ulithi under Vice Admiral Theodore S Wilkinson. Task Force 32 was itself split into the Peleliu Attack Group (1st Marine Division) directly under Fort and the Angaur Attack Group (81st Infantry Division) under Rear Admiral H P Blandly.

Halsey Steps In

Admiral William F 'Bull' Halsey, Commander of the Western Pacific Task Force, had overall responsibility for conducting supportive attacks against a number of Japanese bases both in the Palau Islands and in the Philippines. As these raids were taking place, the invasion force was heading towards Peleliu, but to Halsey's surprise, these raids were only lightly contested, making Halsey suspect that the Philippines (in particular) were not as heavily defended as first thought. He ordered his Chief of Staff, Rear Admiral R B Carney to send an urgent message to Admiral Nimitz just two days (13 September) before the assaults on Peleliu and Morotai were to take place, recommending that firstly, the assaults be abandoned, secondly, that the ground forces that were to be used be transferred to MacArthur for use in the Philippines and thirdly, that the invasion of Leyte be conducted at the earliest opportunity.

Nimitz in turn, quickly sent a message to the Joint Chiefs of Staff who were, at that point, meeting in Quebec for the Octagon Conference with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The Joint Chiefs, after consultation with General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz, decided on the 14 September (the day before D-Day) that the landings on Leyte should be brought forward by two months, thus accepting the third point in Halsey's recommendations. Halsey therefore, cancelled the second phase of Stalemate II on 17 September, with the exception of the landing on Ulithi, which would be now be carried out by the 323rd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 81st Infantry Division. The XXIV Corps was transferred to MacArthur's command and landed on Leyte on 20 October 1944, fulfilling MacArthur's promise to return to the Philippines as soon as possible.

The Peleliu and Morotai assaults would go ahead however. While this would have no serious consequences for the 31st Infantry Division assaulting Morotai, the consequences for the 1st Marine and 81st Infantry Divisions would be severe. It was argued that the invasion forces were already at sea and the assault was on the verge of taking place and therefore too late to call it off, the Palau Islands had excellent airfields from which to threaten any invasion force for the Philippines and had a large number of first rate troops that could be used to reinforce them once the invasion was underway. Halsey would always disagree with this decision, claiming these factors could have been neutralised by air and sea bombardment, and whatever their value, the cost in taking them was likely to be too high. The controversy continues to this day.

Planning the Assault

The planning for the Peleliu assault was carried out by the 1st Marine Division's second-in-command, Brigadier General Oliver P Smith, as its commander, Major General William H Rupertus, was away in the United States for a considerable length of time. There were four beaches that the Marines could land on:

The pre-invasion bombardment would be conducted by the battleships USS Pennsylvania, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee and Idaho, the heavy cruisers USS Columbus, Indianapolis, Louisville, Minneapolis and Portland, the light cruisers USS Cleveland, Denver and Honolulu as well as the planes from three fleet carriers, five light carriers and eleven escort carriers. The bombardment was to start on D-3 (12 September) and continue just before the Marines landed, but on D-1 (14 September) Admiral Oldendorf stated he had run out of targets and sent a large number of these ships to the Philippines to support the landings there.

The initial assault would involve the three Marine regiments (1st, 5th and 7th) to land abreast on a 2,200-yard wide beachhead, each with one of their three battalions acting as a regimental and divisional reserve. The 1st Marines under Colonel Lewis B 'Chesty' Puller (less the 1st Battalion in regimental reserve), codenamed 'Spitfire', would land on the left flank on Beach White 1 and 2 and then push inland to a pre-determined point. It would then wheel left to attack the southwest end of the Umurbrogol Mountain, then push northeast along the coastal plain and 'high ground' (as intelligence described it) all the way to Ngesebus Island with the 5th Marines to their right. The 5th Marines under Colonel Harold D 'Bucky' Harris (less the 2nd battalion in regimental reserve), codenamed 'Lonewolf' would land on Beach Orange 1 and 2. The 1st Battalion would land on the left and link up with the 1st Marines, while the 3rd Battalion would drive eastwards across the airfield to the far shore.

The 2nd Battalion would then land at H+1 (one hour after the start of the assault, H-Hour), pass between the other two battalions and participate in the advance northeast. The 7th Marines under Colonel Herman H Hanneken (less the 2nd Battalion kept as divisional reserve), codenamed 'Mustang', would land on the right flank on Beach Orange 3, drive to the eastern shoreline and then wheel right to mop up the remaining enemy forces in the southwest of the island. The 11th Marines, reinforced with III Amphibious Corps' 3rd Howitzer (155mm) and 8th Gun (155mm) Battalions, would start landing on H+1 (one hour after the start of the assault, H-Hour) on the Orange Beaches. The 1st (75mm), 2nd (75mm) and 3rd (105mm) Battalions would support the 1st, 5th and 7th Marines respectively, while the 4th Battalion (105mm) would provide general support, as would the 155mm battalions.

The 81st Infantry Division would assault Angaur with the 322nd RCT landing on Beach Red to the north and then push inland to the south and west. The 321st RCT would land on Beach Blue to the east and push west and south, tying in with the 322nd RCT. Upon completion, the 81st would revert to III Amphibious Corps reserve, garrisoning both Peleliu and Angaur after they were declared secure.

The Assault Force

The two assault formations for Operation Stalemate II were the 1st Marine and 81st Infantry Divisions. The Marines would assault Peleliu itself while the Infantry would assault Angaur and Ulithi. The 1st Marine Division was raised in February 1941 from the 1st Marine Brigade, stationed at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. It had fought on Guadalcanal, America's first amphibious landing of the war and secured a beachhead on Cape Gloucester, New Britain and fought there from December 1943 until February 1944. They then established a camp on Pavuvu in the Russell Islands, a small, inhospitable island some 35 miles northeast of Guadalcanal that was totally inadequate (initially anyway) as a base of operations and for training. They would reluctantly return there to prepare for Okinawa. Many of the veterans of Guadalcanal had rotated back to the USA, but some remained and most had fought on New Britain having fought in one of the wettest campaigns of the Second World War. The result of that campaign was that the division was in less than an ideal condition (many men suffering from weight loss and fungal infections) and had to absorb almost 5,000 replacements.

The division reorganized under the May 1944 TO&E, which saw the detachment of the 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion to Fleet Marine Force control but it remained with the division and was eventually split three ways to form the 3rd Armored Amphibian Tractor (also known as Landing Vehicle, Tracked, LVT or amtrac) and 6th Amphibian Tractor Battalions (Provisional). Many of the personnel were drawn from the rear echelons of other amtrac battalions, Company C, 1st Motor Transport Battalion and the Tracked Vehicle School in the USA. Few LVTs were available to help train the three units but enough LVT(2)s and the new LVT(4)s existed to equip the units for the operation. As for the remainder of the 1st Motor Transport Battalion, Company A landed with its full complement of trucks and repair equipment, while Company B landed as litter bearers and relief drivers. There was also the deactivation of the 1st Special Weapons Battalion, which was spread among the infantry regiments. The scout company was detached from the tank battalion and redesignated the 1st Reconnaissance Company and assigned to the divisional headquarters battalion. 'Light' was dropped from the division's tank battalion as it received M4A2 Sherman medium tanks armed with 75mm guns and the companies changed from having three five-tank platoons to four three-tank platoons with three tanks in the headquarters. This allowed for a more flexible approach to assigning platoons to infantry battalions but with only three tanks, any combat losses could render the platoon ineffective. Company C of the tank battalion did not deploy due to restricted shipping space, but the crews were landed to serve as replacements. Thirty tanks were initially deployed but replacements did arrive as forty were knocked out during the battle and some twenty tanks were kept operational. The engineer regiment (17th Marines) was deactivated, and the component battalions being assigned to headquarters control (the Naval Construction Battalion or Seabees, returned to the Navy). The artillery regiment (11th Marines) lost its 3rd Battalion, which was rearmed with 155mm guns and placed under Fleet Marine Force control while the 5th Battalion became the new 3rd Battalion. Thus the 1st and 2nd Battalions were armed with 75mm M1A1 pack howitzers, and the 3rd and 4th Battalions were equipped with 105mm M2A1 howitzers. Finally, the infantry regiments were reorganized, each with a 261-man headquarters and service company (losing the scout and sniper platoon), a 203-man regimental weapons company and three 954-man infantry battalions. The weapons company had a platoon of four 75mm M3A1 halftrack-mounted guns and three platoons of four 37mm anti-tank guns each. The infantry battalions lost their weapons companies (D, H, M) - the mortar platoon (of four 81mm mortars) going to the headquarters company and the three heavy machine gun platoons were absorbed into the machine gun platoons of the rifle companies. The headquarters had twenty-seven M1A1 flamethrowers and twenty-seven demolition kits, one for each rifle squad. Sometimes the companies formed special assault squads armed with these weapons to attack enemy pillboxes or bunkers. For Operation Stalemate II, the division was given 100 60mm T20 shoulder fired mortars to issue to the platoons for use against caves and pillboxes. The rifle companies had a 53-man headquarters, three 46-man rifle platoons and 56-man machine gun platoon. The machine gun platoon had six .30cal M1919A4 air-cooled light machine guns, six .30cal M1917A1 water-cooled heavy machine guns, three 60mm M2 mortars (assigned to the company headquarters) and three 2.36in M1A1 rocket launchers. The rifle platoons each had a 7-man headquarters and three 13-man rifle squads. The rifle squads had a squad leader armed with an M1 carbine and three 4-man fire teams, each with a fire team leader (M1 rifle, M7 grenade launcher), rifleman (M1 rifle, M7 grenade launcher), automatic rifleman (M1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle - BAR) and an assistant automatic rifleman (M1 carbine, M8 grenade launcher).

The 81st Infantry Division was made up of the 321st, 322nd and 323rd Regimental Combat Teams (RCTs) and was to assault both Angaur (321st and 322nd RCTs) and Ulithi (323rd RCT) but only when released by the 1st Marine Division commander. The 81st had been reactivated at Camp Rucker, Alabama in June 1942 after having previously served during World War One. It was raised from a small regular Army cadre from the 3rd Infantry Division, and filled out with newly commissioned reserve officers and conscripted troops. It received extensive desert training, participated in corps level exercises stressing the attack of fortified defensive positions, amphibious training in California, and was finally transferred to Hawaii where it undertook additional amphibious training. It was transported to Guadalcanal (by then a major US base) where it received jungle training, acclimatization and training in rugged terrain. Angaur and Peleliu would be its first combat action.

Army infantry regiments had a 108-man headquarters with a platoon of three 37mm M3A1 anti-tank guns and a intelligence / reconnaissance platoon, a 118-man canon company with six 75mm M1A1 pack howitzers, a 165-man anti-tank company with nine 37mm anti-tank guns with a mine platoon, and a 115-man service company. It had three 871-man infantry battalions, each with a 155-man headquarters, three 193-man rifle companies and a 160-man heavy weapons company (D, H, M) with eight .30cal M1917A1 heavy machine guns in two platoons, and six 81mm M1 mortars in another. Each rifle company consisted of three 39-man platoons, each having three 12-man squads with a squad leader (M1 rifle), automatic rifleman (M1918A2 BAR), assistant automatic rifleman (M1 rifle), grenadier (M1 rifle, M7 grenade launcher) and seven riflemen (M1 rifles). The company had five 2.36in M1A1 bazookas and a weapons platoon with a section of two .30cal M1919A4 light machine guns and a section of three 60mm M2 mortars. Army divisional artillery was organized in a different way to that of the Marines, in that a Brigadier General was in command, had three 105mm M2A1 howitzer battalions (316th, 317th and 906th Field Artillery Battalions) and one 155mm M1A1 howitzer battalion (318th). Each battalion had a headquarters and headquarters battery, service battery and three howitzer batteries with four tubes apiece. The divisional tank battalion was the 710th, had four companies, three with seventeen M4A1 Sherman tanks (three platoons of five and two in the headquarters), and a fourth with 3in gun armed M10 tank destroyers. It also had six 75mm M8 self-propelled howitzers in the assault gun platoon attached to the headquarters.

The assault force for Operation Stalemate II therefore numbered approximately 47,561 (2,647 officers, 44,914 men), of which 26,417 (1,438 officers, 24,979 men) were Marines.

The Japanese Prepare

The loss of the Marshall Islands and the bypassing of Truk and the Caroline Islands prompted the Japanese into a serious rethink of their defensive strategy as they were being pushed back on all fronts. These deliberations prompted the creation of an 'Absolute National Defense Zone', the equivalent of a 'line in the sand' that would be held at all costs and the Palau Islands became a part of that defense zone, initially under the command of the 31st Army headquartered in Truk (under Lt General Hideyoshi Obata), and subsequently transferred to the Southern Army in Manila (Field Marshal Count Hisaichi Terauchi). The islands already had some forces stationed there under the command of Major General Takso Yamaguchi, which consisted of the Sea Transport Unit of the 1st Amphibious Brigade, replacement units for the 20th, 41st and 51st Divisions, as well as supply and rear echelon units. These were formed into the 53rd Independent Mixed Brigade, consisting of a headquarters, five infantry battalions (346th, 348th, 349th, 350th and 351st), an artillery unit and an engineer unit.

To bolster the defences, both the 35th Division and subsequently the 14th Division were ordered to the Palau Islands - however, the 35th Division was redirected to New Guinea. The 14th was already en route to New Guinea but was then redirected to Saipan and subsequently to the Palau Islands. This was under the command to Lt General Sadao Inoue and was a veteran formation from the Kwantung Army with a distinguished history dating back to the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 - 5 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 - 5. It consisted of a headquarters, the 2nd (a 'heavy' Type A regiment), 15th and 59th Infantry Regiments (both Type B 'light' regiments), as well as numerous combat support, and combat service support elements. Inoue took command of the Palau Sector, which included Yap - defended by the 49th Independent Mixed Brigade and 46th Base Force - and Ulithi. He deployed the 15th Infantry Regiment (-3rd Battalion) and 59th Infantry Regiment (-1st Battalion) on Babelthuap, along with the 53rd Independent Mixed Brigade (-346th Independent Infantry Battalion). The 2nd Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion / 15th Infantry Regiment, 346th Infantry Battalion, the 14th Division's Tank Unit and other miscellaneous units were deployed on Peleliu (under Colonel Kunio Nakagawa) and the 1st Btn / 59th IR (Reinforced) defended Angaur under Major Ushio Goto. There were also numerous combat support and combat service support units that were organised into combat units once the invasion began.

The senior Imperial Japanese Navy commander for the Palau Islands was Vice Admiral Yoshioka Ito (sometimes spelt Itou and called Kenzo Ito which has created confusion) commanding the 30th Base Force. It is doubtful he was on Peleliu at the time of the battle as he survived to surrender Imperial Japanese Navy forces in the Palau Islands to the Americans in April 1945. Many references state that the overall naval commander for Peleliu was Vice-Admiral Seiichi Itou, but Jim Moran and Gordon Rottman argue that Vice-Admiral Seiichi Ito (not Itou) was in fact the Vice Naval Chief of Staff and in Japan at the time. He was in command of the battleship Yamato's suicide mission to beach itself on Okinawa and went down with the ship when it was sunk. No source can be found naming the senior naval commander on Peleliu.

The defense of Peleliu would be conducted with new tactics - no longer would the Japanese try and hold the landing beach in strength, where they could be subjected to fierce aerial and naval bombardment but would lightly defend the beach, construct a defense in depth utilizing the terrain to best advantage and counterattack on the first night while the Americans were still consolidating the beachhead. Additionally, there would be no mass suicidal banzai attacks, but carefully coordinated small-scale counterattacks - the Japanese planned to fight a war of attrition and bleed the Americans white.

The Japanese defenders numbered approximately 21,000 Army, 7,000 Navy and 10,000 laborers on the Palau Islands.

The Americans Move

After the time spent resting (or not as the Marines had to construct even the most basic of facilities, but at least there was some light relief as Bob Hope and his show stopped off before they departed) and training on Pavuvu, the Marines conducted two full-scale rehearsals on 27 and 29 August. This had naval gunfire to add realism but the Tassafarongo region on Guadalcanal lacked an inshore reef and so the hazardous task of transferring men and equipment from landing craft to amtrac could only be simulated. The practice landing resulted in a number of casualties from broken limbs, most notably Major General Rupertus who suffered a broken ankle. After this came an uneventful 2,100-mile voyage to the concentration area near the Palau Islands.

Starting on the 12 September, Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) 6 and 7 had been clearing submerged obstacles and blasting pathways through the reef at Peleliu for the assault waves, while UDT 8 did the same on Angaur. This was often dangerous work and in many cases carried out under direct small arms fire from Japanese defenders on the beach. The Kossol Passage north of Babelthuap was cleared of mines at a cost of a minesweeper (USS Perry) with another minesweeper and a destroyer (USS Wadleigh) damaged.

Naval support ships began the pre-assault bombardment at 05.30, 15 September 1944, which moved inland at 07.50 to make way for carrier-based aircraft to bomb and strafe the beaches ahead of the lead assault wave. White phosphorous smoke shells were fired to screen the incoming Marines from the Japanese on the high ground to the north of the airfield. The initial assault waves would be landed entirely by amtrac, with subsequent waves transferring from LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel or 'Higgin's Boats' after their inventor, Andrew Higgins) at the reef's edge to amtracs returning from the beaches. This is basically a re-run of the plan for Operation Galvanic, the assault on Tarawa, and many a Marine must have thought about their comrades in the 2nd Marine Division who had had to wade ashore several hundred meters under intense fire from the Japanese. This time however, they would be preceded by LVT(A)1s, which mounted a 37mm gun, or LVT(A)4s, which mounted a 75mm gun and were specially armored amtracs that could act as tanks and suppress beach defenses. Additionally, there would be eighteen LCI(G)s (Landing Craft, Infantry (gun)), armed with 4.5in rockets and four LCI(M)s (Landing Craft, Infantry (mortar)) armed with three 4.2in mortars to give fire support to the assault troops. As the first waves crossed the line of departure, it became apparent that there were still plenty of defenders on Peleliu as artillery fire and mortar shells started to land in amongst the amtracs racing for the beach. A number received direct hits (some twenty-six were knocked out on D-Day) and the smoke and debris thrown up by both the American and Japanese bombardment obscured the beaches for a time from the following waves.

Hitting the Beach

The 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (3/1) were the first to land, reaching Beach White 1 at 08.32 with the 2nd Battalion (2/1) on its right (White 2) and 1st Battalion (1/1) due to arrive at 09.45 as regimental reserve. 2/1 advanced some 350 yards with the support of the armored amtracs, at which point their Sherman tanks had arrived ashore. They stopped at the far side of some woods, facing the airfield and its buildings, having linked up with the 5th Marines. 3/1 faced stronger opposition than 2/1 and after it had advanced 100 yards faced an extremely formidable obstacle, a 30-foot high rough coral ridge (nicknamed 'The Point'), which had not been on any map and was covered with caves and defensive positions that the Japanese had blasted into the ridge. It resisted all initial assaults and even after tank support had arrived, the assaulting troops ran into a large anti-tank ditch that was dominated by the ridge and the Marines were pinned down for hours. A and B Companies of 1/1 were committed in support but it wasn't until late in the afternoon that a foothold was gained on the southern part of 'The Point'. A number of LVTs had been hit on the way in and this had badly disrupted the 1st Marines command group. As a result, two serious gaps had started to appear in the 1st Marines lines and the division headquarters only slowly became aware of it. Every available person (including headquarters personnel and 100 men from the 1st Engineer Battalion) was drafted to fill them and they formed a defence in depth against any possible Japanese counterattack, that could have rolled up the line and attacked onto a congested beach. Eventually, some Marines from Company K (K/3/1), under Captain George B Hunt managed to fight their way inland and attack 'The Point' from the rear. They fought their way along it for over two hours. They then came to the main defensive installation, which was a reinforced concrete casement that was armed with a 25mm automatic cannon and had been raking the beach all morning. Lieutenant William L Willis dropped a smoke grenade to cover the attack while Corporal Anderson managed to launch a rifle grenade through the firing aperture that damaged the gun and set off the ammunition. Any surviving defenders were taken care of as they left the position. Captain Hunt and his thirty surviving men spent the next thirty or so hours beating off attempted Japanese infiltrations.

The 5th Marines landed on Beach Orange 1 (1/5) and 2 (3/5) and meeting only scattered resistance, advanced inland through coconut groves and reaching their first objective line by 09.30 and tying up with 2/1 on their left. There was some confusion on Orange 2 as elements of the 7th Marines landed there instead of their intended beach (Orange 3) and so the 3rd Battalion's K Company (K/3/5) was delayed in its advance and did not draw level with I/3/5 until 10.00. After 3/5 resumed the advance at 10.30, there was again some confusion between its companies as K/3/5 forged ahead of I/3/5 as it was in dense vegetation that provided concealment from Japanese shelling. L/3/5 was committed to close the gap but the line remained thin for much of D-Day. 2/5 had landed at 09.35 and drove east and they were deployed to relieve I/3/5 who were to pass around L/3/5 and tie in with K/3/5. Orders proved easier to give than to execute and it took sometime to accomplish this. To underscore 3/5's bad luck, a mortar barrage hit the battalion command post (CP) and Colonel Shofner and a number of his staff were wounded and had to be evacuated, forcing Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W Walt, the battalion's Executive Office, to take command.

The 7th Marines landed on Beach Orange 3, with two battalions (1/7 and 3/7) in column, and 2/7 being kept afloat as division reserve. 3/7 landed first but experienced difficulties with a high number of natural and man-made obstacles on the reef, which forced the amtrac divers to approach it in column, presenting a prime target to the Japanese gunners. The ferocious fire that came in forced a number of amtrac drivers to veer left and land on Orange 2. The confusion between 3/7 and 3/5 took time to rectify and when it finally moved off inland it discovered another large obstacle in the form of a huge anti-tank ditch, which the Marines quickly put to good use. By 10.45 3/7 had covered some 500 yards when it ran into a series of blockhouses and pillboxes in the old Japanese barracks area. It requested tank support, which when it arrived, became confused and ended up supporting 3/5 instead of 3/7 as they were adjacent to each other. This led to a gap opening up between the two regiments as 3/7 had stopped to consolidate its position whereas 3/5 continued to push ahead. 1/7 landed on Orange 3 at 10.30 and wheeled right as planned, only to encounter a dense swamp (not shown on any map), which had the only trail around it heavily defended. It wouldn't be until 15.20 that Colonel Gormley could report that the battalion had reached its objective line and it faced a determined Japanese counterattack that night, which was only defeated with the help of Black Marine shore party personnel who volunteered to become riflemen.

While there were a number of local counterattacks that night, none were of the old suicidal banzai variety. Instead they took a more coherent form of carefully planned attempts at infiltration and raiding. The only major counterattack of the day came in at 16.50 and consisted of a combined tank - infantry force that crossed the northern part of the runway. Initially, an infantry force started to move towards Marine lines under the cover of a significant increase in artillery fire and was soon followed by a group of tanks with infantry riding on them. For a moment, this looked like a serious coordinated attack but then for some reason the Japanese tank drivers accelerated towards the Marines, leaving the infantry in their wake. They cut across the front of 2/1 who subjected them to devastating flanking fire. Two of the tanks veered off and went through 2/1's lines and crashed into a swamp while the others went through the lines of 1/5 and were cut to pieces. The advancing infantry was subject to harassing fire and the attentions of a Navy dive-bomber. Only two tanks escaped (these were probably destroyed in a later counterattack) and the infantry disappeared after seeing their tank support decimated.

Preparing for the Meat Grinder: D+1 to D+7

Major General Rupertus and his staff landed at 09.50 on D+1 (16 September) and took over the command post set up by General Smith in the large anti-tank ditch. They immediately set to work on the next phase of the campaign based on the original battle plan, despite the fact that few of the original D-Day objectives had been met and the 1st Marines were in serious trouble on the left flank.

On the right, the 7th Marines continued their advance south and east. 3/7 continued their assault eastwards on a large Japanese reinforced concrete blockhouse with the aid of naval gunfire support and artillery, but had to finally reduce it by direct assault under cover of a smokescreen. 1/7 attacked south over flat scrubland that slowed progress. Most of the defenses in this area were geared to a possible assault from the sea, but the Marines still faced a large number of casemates, bunkers, blockhouses, pillboxes, rifle pits and trenches, all mutually supporting with well-cleared fields of fire. It took most of the morning on D+1 for K/3/7 to reach the far shoreline. It must be noted that the temperatures on Peleliu were not comfortable at all, with it being over 100° F and the strains of protracted fighting and dehydration would soon be felt. The advance was halted at noon, with the rest of D+1 taken up with bringing forward and stockpiling fresh supplies and water. Unfortunately a number of the drums used to hold the water had previously been used to store aviation fuel and a large number of Marines were temporarily incapacitated.

D+2 saw the 7th Marines continue their assault to the south and southeast with 3/7 taking the Southeastern Promontory by 13.20 after some fierce fighting and the clearance by Engineers of a minefield that delayed the attack. 1/7 started their assault on the Southwestern Promontory (much larger than the southeastern one) at 08.35 and met stubborn resistance from the beginning and had to call in tanks and armored LVT(A)s to help the advance. They managed to take the first line of the Japanese defenses by mid-afternoon but only managed to clear half the promontory by nightfall. They resumed the attack at 10.00 on D+3 but progress was slow (even though additional armour and 75mm gun armed halftracks had been brought up) with many rear echelon elements being attacked by Japanese emerging from bypassed caves and fortifications. It wasn't until mid-afternoon that the Marines had reached the southern shore and the remaining Japanese decided to take their own lives and save the Marines the trouble. The southern part of Peleliu had been secured.

Meanwhile, the 5th Marines prepared to continue to advance east and then swing northeast to stay on the right flank of the 1st Marines. In a short space of time, 1/5 swept the whole of the northern part of the airfield with the only serious resistance coming from a collection of emplacements around the hangars. The area was secured by the end of D+1 after heavy fighting and an adjustment in the frontline. 2/5 (to the right of 1/5) was making slow progress over what was relatively open ground due to heavy resistance. To the east of the airfield, woodland gave way to a mangrove swamp that were all infested with Japanese fortifications and it took hours of hand-to-hand fighting for 2/5 to draw next to 1/5. With the advances of the 7th Marines on their right flank and the 2/5 on its left flank, 3/5 was almost pinched out of operations by the end of D+1 and halted to secure its positions on the shoreline. D+2 saw the 5th Marines start moving northeast where they came under flanking fire from Japanese positions in front of the 1st Marines. 1/5 reached its objectives by noon but when 3/5 relieved it and tried to continue the advance, it became pinned down. 2/5 however had greater success, being concealed by woodland, and with resistance being light quickly drew level with 3/5 on its left and the shoreline to its right. D+3 (18 September) saw the 5th Marines make slow but steady progress. The regimental boundary (on their left) was the road that ran past the Umurbrogol Mountain to the northeast. 2/5 hacked its way through dense jungle terrain to eventually come across an improved road that split, in one direction running east towards Ngardololok and in the other running northeast past the Kamilianlul Mountain and Hill 80 before it joined another road running along the other shoreline past Garekoro. As it ran east, this road ran very close to the swamp and in places could have been considered a causeway that would be perilous to advance up. A patrol was sent in advance of the main body that was covered by artillery and air strikes, one of which came in late and hit the Marines, resulting in thirty-four casualties. With this opening, Regimental HQ shifted 3/5 (minus L Company tied in with the 1st Marines) along the road to support 2/5, which faced the main Ngardololok installations, usually referred to as the 'RDF' as it contained a radio direction finder station. Both battalions advanced on the RDF and by the end of D+4 had reached the eastern and southern shores (Beach Purple). By the end of D+5 they had secured the entire eastern peninsula with 2/5 advancing all the way up to Ngabad Island and then moving across to Carlson Island by D+8.

On the left flank, things were far from going to plan. The 1st Marines under Puller had met fierce and coordinated resistance from the first moments they landed. On D+1, the divisional reserve 2/7 was ordered to support the 1st Marines. 2/1, which faced east, swung north to attack the built-up area that lay between the airfield and the mountains. 3/1 however, was not able to match this and therefore 1/1, the regimental reserve, was landed to give support. After hard fighting, the 1st Marines finally captured 'The Ridge' and relieved Company K, which had been reduced to 78 men from 235. On D+2, the 1st Marines came into contact with the Umurbrogol Mountains and described it thus - "a contorted mass of coral, strewn with rubble crags, ridges and gulches." By this time the 1st Marines had suffered over 1,000 casualties, but all three battalions now lined up with 3/1 on the left, 1/1 in the centre and 2/1 on the right with 2/7 in reserve. 2/1 was the first to advance and engage the defences. They attacked and took the first of many ridges (this one called Hill 200) but immediately came under fire from the next one (Hill 210). 1/1 made good progress until they came up against a reinforced concrete blockhouse that had been reported as destroyed by Admiral Oldendorf. The Marines only took it after calling in 14in naval gunfire directly onto the fortification. 3/1 advanced along the comparatively flat coastal plain, but halted when it started to loose contact with 1/1. Casualties quickly rose but Puller was being urged on by Rupertus to 'maintain momentum' and so just about everyone who could hold a rifle was put into the line as infantry, including engineers, pioneers and HQ personnel. 2/7 moved into the line to replace 1/1. The pattern for D+2 was to be repeated again and again. On D+3 the Marines took Hill 210, but the Japanese counterattacked Hill 200 forcing them to withdraw. The situation looked desperate and so B/1/1 who had just entered reserve, was ordered to re-enter the line and help 2/1 take another ridge (Hill 205). This they accomplished, but when they tried to advance, they were halted by a collection of emplacements and fortifications that came to be known as the 'Five Sisters'. 3/1 advanced along the coastal plain once again, halting to maintain contact with 2/7. After a night of concerted counterattacks, the remnants of the 1st Marines and 2/7 resumed their attacks on what was now obvious to everyone - the main Japanese line of defense - and while making progress suffered heavy casualties. By the end of D+4, the 1st Marines were no longer capable of effective action, having suffered some 1,749 casualties - only six fewer than what the 1st Marine Division had suffered in its entirety on Guadalcanal. Having visited the 1st Marines, Roy Geiger (Commander, III Amphibious Corps) ordered Rupertus to replace the 1st Marines with the 321st RCT, 81st Infantry Division (on Angaur) and send the 1st Marines back to Pavuvu.

'A Horrible Place' to Fight

D+6 saw the completion by Navy Seabees on Beach Orange 3 of a pontoon causeway that would facilitate the unloading of equipment and supplies as it bridged the reef that was impassable to the large LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank). D+8 (23 September) saw 2/5 secure the small island, later named Carlson Island, to the north of Ngabad Island. It also saw the Japanese reinforce the beleaguered garrison on Peleliu with virtually a whole battalion's worth (2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment) of fresh troops that landed by barge from Babelthuap, after two previous attempts had been turned back by the Americans. The need to secure northern Peleliu was now evident.

D+9 saw the 321st RCT, having arrived from Angaur (Angaur being declared secure at 10.34, 20 September, although the 322nd RCT would be fighting there for another month in 'mopping up' operations), drive north past the Umurbrogol Mountains, the plan being for the 321st RCT to push past them, with the 5th Marines moving through them and securing northern Peleliu while the 7th Marines took over the 1st Marine's positions. However, the Japanese still held positions all along the edge of the road and would bring down fire on anything that tried to move along it. The terrain also made it impossible for any tanks or armoured vehicles to move in support of infantry, except along the road. D+9 also saw Marine Air Group 11 start to arrive that would take over the air support for the operation from the Navy.

As the 321st RCT advanced (having taken over from 3/1 that had been tied to 3/7 to their right) they outpaced the 3/7 by keeping to the road, 3/7 having to take the ridges themselves. The 321st RCT continued to advance and by D+10, the 5th Marines were able to pass through them and move onto the ruined village of Garekoru. There, 1/5 occupied the destroyed radio station to the north of the village and 3/5 took the high ground on their right flank after a hard but short fight from Navy construction personnel.

D+11 saw an assault begin on 'Hill Row' made up of Radar Hill, and Hills 1, 2 and 3, in actuality the southern arm of the Amiangal Ridge. Here, 1/5 and 2/5 started the attack, but as it progressed, 2/5 shifted west and continued north while 1/5 and 3/5 continued to attack eastwards, 3/5 taking Hill 80 and reaching the shoreline by the end of the day. Fighting continued on D+11 and D+12 but by the end of D+12 (27 September), 2/5 had secured the northern shore (Akarakoro Point) and the phosphate plant, although it would take another several weeks to finally eliminate all resistance on the Point, by blasting shut the cave entrances. Even then, a few weeks later, the Marines were astonished to see Japanese Navy survivors dig their way out! 2/5 then turned around and attacked south in support of 1/5, still assaulting Hill Row. After two more days of fierce fighting, they had reached the tops of Hill Row, with only the Umurbrogol Pocket left. Meanwhile, 3/5 assaulted Ngesebus Island on D+13 to seal off Peleliu from further reinforcement from Babelthuap. They were supported by the battleship USS Mississippi, the cruisers USS Columbus and USS Denver, land-based artillery and Marine Corsairs from VMF-114. 1/7 was in reserve. The landing (at 09.30) was met with little resistance. Ngesebus is mainly flat and covered with scrubland but has some coral ridges to the west. This was where the Japanese had there main defence line, but it wasn't as well constructed as those on Peleliu, and with the support of tanks, 3/5 had cleared both Ngesebus and Kongauru Island by the end of D+14 and turned them over to 1/321, going into divisional reserve.

Reducing 'The Pocket'

With the north of Peleliu secure, the only part still in Japanese hands was the pocket of resistance centered on the Umurbrogol Mountains in an area of about 1,000 yards by 500 yards, running from Baldy Hill in the north to Five Sisters in the south. The 7th Marines continued to press from the south and west while 2/321 and 3/321 pressed from the north, having taken over from the 5th Marines. Hill B, which had stalled 321st RCT's attack, was finally taken on D+11 by 2/321with the help of a specially formed unit, called 'Neal Force' made up of seven Sherman tanks, six LVTs, an LVT flamethrower and forty-five riflemen. On D+14 the 7th Marines were tasked with relieving 2/321 and 3/321 but in order to release 1/7 and 3/7 from their holding positions, two composite units made up of drafted support personnel were formed, to take up positions alongside 2/7 and a weapons company. Also, the 1st Tank Battalion was withdrawn by Major General Rupertus, who considered tanks to be of little use in the fighting ahead, despite the objections by the second-in-command, Brigadier General Oliver P Smith. Added to that a typhoon appeared and lasted for three days in which the Americans had to organize emergency supply flights by C-46 and C-47 aircraft, as it was impossible for them to land supplies on the beach. While the rain reduced the temperature, it turned the dust into mud making movement difficult over most of the island.

1/7 and 3/7 relieved 321st RCT on D+14 and on D+15 renewed the assault southwards, managing to take part of 'Boyd Ridge' and Hill 100 (also sometimes called Pope's Ridge or Walt Ridge). 3/5 (back from Ngesebus) reinforced the 7th Marines on D+18 and so the regiment planned a four-battalion attack. 1/7 (along the East Road towards the unnamed ridge) and 3/7 (towards Baldy Hill) would attack from the north. 2/7 would attack towards Hill 300 from the south and 3/5 would make a diversionary attack towards Five Sisters and Horseshoe Canyon from the west. After bitter fighting and heavy casualties, the assault managed to secure its objectives with the exception of the Five Sisters, where 3/5 had managed to scale four out of the five heights but had to retreat as its position was untenable. It was on D+18 that the Marines suffered their highest-ranking casualty - Colonel Joseph F Hankins, who had come down the West Road to clear a traffic jam near a dangerous part of the road called 'Dead Man's Curve', and was killed by a sniper.

The 7th Marines had been in the Umurbrogol for two weeks and were looking severely battered as a result. D+19 saw their final attack get underway to mop up the draw between Walt (also known as Hill 100) and Boyd Ridges, which were assigned to I/3/7 and F/2/7. Company L under Captain James V Shanley was tasked to seize three semi-isolated hills east of Baldy. The company achieved this with no casualties and so continued to advance onto Ridge 120. Just as the lead platoon reached to northern tip of the ridge, Japanese opened up with automatic fire from emplacements on Baldy and the lower slopes of Boyd Ridge. As the Marines retreated they walked into an ambush - a hail of fire from positions on the captured knobs and the lower slopes of Ridge 120. It was all over by 18.20 - only five Marines out of the forty-eight in the platoon made it back unhurt. The 7th Marines were no longer an effective fighting force having suffered 46 percent casualties (1,486 out of 3,217). They were pulled out of the line and replaced by the 5th Marines, 1/5 taking over from 2/7 and 2/5 taking over from 3/7, while 3/5 withdrew to a bivouac area to prepare for up-and-coming operations.

Bulldozers were brought up to clear routes into the many canyons to allow flamethrower-equipped LVTs and tanks to support the advance and artillery was positioned on the West Road to fire at point-blank range at the west facing cliffs. These tactics continued, slowly reducing the pocket, for the next six days. Hill 140 was captured in a well-orchestrated attack from 2/5 that allowed a 75mm pack howitzer to be brought up, sandbagged in place, and fire on many of the larger caves that had been firing to such devastating effect on the attacking Marines. D+27 saw 3/5 relieve 2/5 and continue the attack from the southeast, gradually reducing the Pocket to an area 800 yards long by 500 yards wide.

Rupertus had been resisting suggestions by Major General Geiger to relieve the 5th and 7th Marines with the 321st RCT but Rupertus desperately wanted the Umurbrogol Mountain to fall to the Marines and limit the Army's role to mopping up only. Events however, overtook him with first, the arrival of the 323rd RCT from Ulithi and secondly the replacement of Admiral Wilkinson by Admiral Fort who promptly sent a communiqué to the effect that Peleliu had been secured and that the 1st Marine Division would be withdrawn to Pavuvu, the assault phase of Operation Stalemate II complete. Over the course of D+31 / 32 the 321st RCT relieved the 5th Marines while the 323rd RCT relieved the 7th Marines. A number of Marine units (including the 1st Amphibian Tractor, 3rd Armored Amphibian Tractor and 1st Medical Battalions) stayed on to support the 81st Infantry Division in a battle that lasted another six weeks. Japanese defenses were now concentrated in individual positions around Baldy, Hill 140, Five Brothers, Five Sisters and the China Wall. The Army continued to pound the Japanese, and reduce each position carefully with intense preparatory work. The 321st RCT continued the attack and took the Five Brothers and entered the Horseshoe on 23 November. 323rd RCT (under Colonel Arthur Watson) took Hill 30 and Five Sisters and after assuming the main responsibility for finishing the attack, started their assault on the China Wall, only yards from Nakagawa's command post in what was to be the last Japanese position on the island to fall. Engineers constructed a ramp to allow tanks and flame-throwing LVTs to fire directly onto the last Japanese defenses now only a couple of hundred yards square. On D+70, Colonel Nakagawa sent one last message to Koror advising them that he had burned the 2nd Infantry Regiment's colors and split his remaining 56 men into 17 groups with orders to attack the enemy wherever they found them. That night, 25 Japanese were killed attempting to infiltrate American lines and the following morning, a prisoner confirmed that Colonel Nakagawa and Major General Murai had both committed ritual suicide in their command post. On the morning of D+73 (27 November), elements from the north and the south met face-to-face near what was Nakagawa's final command post. Colonel Watson reported to Major General Mueller that the operation was over, although mopping up would continue for some time to come.

The Aftermath

The cost was staggering. The Marines suffered 1,300 dead, 5,450 wounded and 36 missing. The 1st Marines suffered 1,749 casualties, the 5th Marines suffered 1,378 and the 7th Marines suffered 1,497. The Army suffered 1,393 casualties (208 killed) on Peleliu and 1,614 casualties (260 killed) on Angaur. The Japanese lost an estimated 10,900 personnel, including those lost at sea in reinforcement attempts. 202 prisoners were taken, of which 19 were Japanese, the rest being Korean or Okinawan laborers. Only 39 prisoners were taken on Angaur with the rest of the 1,400-man garrison being wiped out.

One mystery surrounding Peleliu was the role played by Major General Kenjiro Murai. Captured orders and interrogation of POWs indicated that Colonel Nakagawa was in command and that Murai was there as an advisor as he was considered an expert in fortifications. This was an unusual situation to say the least given the disparity in rank, strict Japanese military code and the fact that Peleliu was a large command for a colonel. In March 1950, Lt Colonel Worden, USMC, interrogated General Inoue, who survived the war, while he was in a US Navy prison. Inoue's statement, plus captured material from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed that Murai was definitely on Peleliu during the fighting and that both he and Nakagawa received special promotions on 31 December 1944, the day that the Japanese High Command accepted their deaths. There was however problems between the Army and the Navy and it is possible that Inoue sent Murai there to bolster Nakagawa's authority as the Army were finding it difficult to obtain any sort of real cooperation from the Navy. However, a Navy vice-admiral still outranks an Army Major General, although not by nearly as much as a colonel.

For months afterwards, US garrison troops were flushing out survivors and sealing up caves. The huge tunnel complex in the Umurbrogol was still occupied and after attempts were made to persuade the Japanese to surrender, the caves were sealed shut, only to have five bedraggled survivors dig their way out in February 1945. For a while after the end of the Second World War, rumors persisted about surviving Japanese soldiers still hiding out in the mountains and swamps of Peleliu. Eventually some 120 Marines were sent in to look for them, as they might be preparing to attack Navy dependent housing. After several attempts to persuade them to give themselves up failed, a former Japanese Admiral was brought to Peleliu to talk them into surrendering and that they could do so with honor. On 22 April 1947, a lieutenant with twenty-six men from the 2nd Infantry Regiment and eight from the 45th Guard Force sailors emerged - their battle for Peleliu finally at an end. This was the last official surrender of World War Two, although the last reported Japanese soldier actually surrendered in 1955!

Navy Seabees started constructing a 7,000-foot runway on Angaur even before the fighting had finished, from which Marine aircraft wings (eventually VMF-114, VMF-121, VMF-122, VMTB-134, VMF(N)-541 and VMR-952 would be based there) started flying to support the troops still battling for the island. It was eventually used by 494th Heavy Bombardment Group flying B-24 Liberators to support American forces fighting in the Philippines as well as two US Navy sea search units, one of which found the survivors of the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) that delivered parts for the atomic bomb to Tinian and was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine (I-58) as it headed for Leyte. The ship went down in twelve minutes and no report of its sinking or a distress call was received. Out of a crew of 1,196, 316 were still alive by the fourth day when they were spotted by a search plane operating out of Peleliu.

Conclusion

A number of lessons needed to be learned in regard to the Peleliu operation. The first was in regard to replacement combat troops. Two 150-man replacement companies were available to the 1st Marine Division and were attached to the 1st Pioneer Battalion as Companies D and E to assist with unloading until D+3 (19 September) when they were released to the regiments. Even by that point, they proved inadequate to replace the losses suffered in the battle. No other replacements were available to the division, which was eventually forced to hand over the battle to the Army's 81st Infantry Division between 15 and 20 October. Two approximately 1,350-man replacement units were available to each Marine division at Iwo Jima, but even these were inadequate.

The second was in the provision of adequate medical care. The 1st Marine Division relied on organic support with each infantry battalion having a 44-man aid station (two officers, forty-two enlisted) that were in fact Navy personnel. Medical corpsmen were attached to the platoons an also operated small aid stations for the rifle companies. The infantry regiments also had aid stations with twenty-four personnel (five officers and nineteen enlisted) in them and a 102-man medical company attached to the division, which provided small clearing stations to support each battalion aid station. This provision was stretched given the casualty rate suffered by the division in the battle.