USS Elmore

- home Home

- flag Start Here

- Featured Section

- What's New?

- The Inside Story

- Dedication

- Stories

- Bulletin Board

- Web Tech

- Team Elmore

- Contact Us

- The Ship

- 42 Overview

- What Is an APA?

- APA Classes

- APAs

- Higgins Boat

- Blueprints

- Perspectives

- Modern Amphibs

- Weapons

- GE Turbine

- Elmore Post-War

- people The Crew

- Remembrance

- Survivors

- Crew List

- Officer List

- Passengers

- Crew Photos

- Shipboard

- Memorabila

- Recollections

- Reunions

- The Logs

- Battle Stars

- Timelines

- War Diary

- Deck Logs

- Ship's History

- Life Aboard a Transport

- Nice to Have You Aboard

- The War Effort

- Pacific Fleet

- Admirals

- Nimitz

- Halsey

- Turner

- MacArthur

- MacArthur Biography

- Man of the People

- The Truth Behind the Photograph

- MacArthur's Navy

- MacArthur Mini-Bio

- Marines

- Army

- Homefront

- Magic Carpet

- The Pacific War

- Overview

- Strategy

- Pacific War

- Pacific Islands

- Ulithi

- Guam

- Tokyo Rose

- Magic

- Kamikaze Main

- Suicide Squad

- Ten Facts

- Divine Wind

- Baka

- USS DuPage

- USS LaGrange

- The Atomic Bomb

- Graphical View

- A-Bomb Timeline

- The Bomb

- Bombs Compared

- Justified?

- Surrender

- Occupation

- Matsuyama

- Wakayama

- Commentaries

- Joe Rosenthal

- Maps

- Maps 1

- Maps 2

- Photos

- Ship Photos

- War Photos

- Videos

- Video 1

- Video 2

- Video 3

- Video 4

- Resources

- Recommended Books

- Book List 1

- Book List 2

- Book List 3

- Book List 4

- Book List 5

- Book List 6

- Book List 7

- Book List 8

- All Hands

- All Hands 1942

- All Hands 1943

- All Hands 1944

- All Hands 1945

- All Hands 1946

- War Posters

- Museums

- Other Websites

- search Search

- question_answer Contact Us

Elmore's Claim to Fame in HBO's The Pacific

The Pacific Connection

Learn about the Elmore's connection to events presented in the HBO miniseries The Pacific (2010).

The Elmore's Connection with "The Pacific"

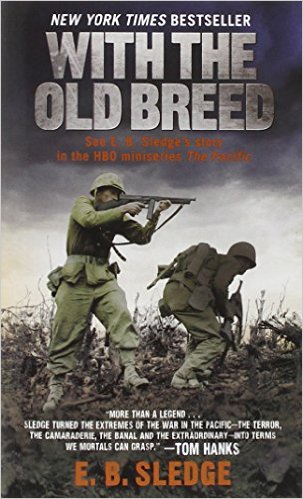

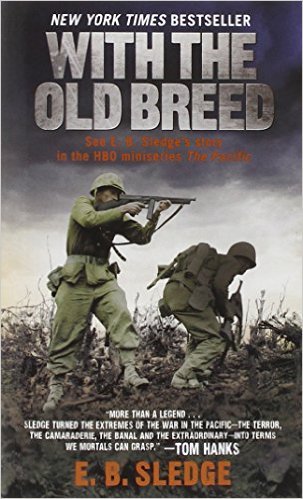

The HBO miniseries The Pacific is a dramatic account of the actual stories of three marines who served in the Pacific during WWII. One of those men was Eugene Sledge (A.K.A., "Sledgehammer") who wrote With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa (1981). This book has been recognized as one of the best first-hand accounts of combat in the Pacific during World War II. The memoir is based on notes Sledge kept tucked away in a pocket-sized Bible he carried with him during battles he fought at Peleliu and Okinawa. He served with Sergeant R.V. Burgin, PFC Merriell "Snafu" Shelton and 1st Lieutenant Edward “Hillbilly” Jones. Nicknamed "Sledgehammer" by his comrades, Sledge achieved the rank of corporal in the Pacific Theater and saw combat as a 60 mm mortarman at Peleliu and Okinawa. When fighting grew too close for effective use of the mortar, he served in other duties such as stretcher bearer and as a rifleman.

Sledge was part of K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division (K/3/5).

"Eugene Sledge became more than a legend with his memoir, With The Old Breed. He became a chronicler, a historian, a storyteller who turns the extremes of the war in the Pacific—the terror, the camaraderie, the banal and the extraordinary—into terms we mortals can grasp."

The Elmore's connection occurred in May of 1944 when the ship transported K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division (K/3/5) from New Britain to Pavuvu in the Russel Islands in early May 1944. Sledge himself was not aboard the Elmore, arriving at Pavuvu a few weeks later. However, the company's commanding officer, 1st Lieutenant Edward “Hillbilly” Jones and Sledge's mortar team leader, Sgt. Romus V. Burgin were on the Elmore. The the dark and brooding PFC Merriell "Snafu" Shelton was also onboard. These men were essential parts of the unfolding events that occurred on Pavuvu and later on Peleliu. It was USS Elmore that brought them to Pavuvu.

In one episode of The Pacific, we are introduced to Eugene Sledge when he reports for duty on Pavuvu. This is where the Marines spent the next four months preparing for the invasion of Peleliu. K Company departed Peleliu on 26 August 1944 in LST 661. The Battle of Peleliu commenced on 15 September 1944 and lasted until 27 November 1944. Elmore was one of the attack transports involved in the initial assault on Peleliu.

Sgt. Burgin mentions the Elmore several times in his book, Islands Of The Damned, A Marine At War In The Pacific (2010). Those quotes are listed below.

"R.V. Burgin is one of those American boys who became a Marine—no small feat. He then went across the Pacific, returning home to Jewett, Texas only after helping to save the world. Read his story and marvel at the man...and those like him.”

From the Elmore’s War Dairy for 4 May 1944:

Anchored Borgen Bay, New Britain, [Papua, New Guinea] with units of Task Unit 34.9.5. At 0045, completed discharging troops and cargo of units of the 40th Division U.S. Army, after having disembarked 488 men and 30 officers. At 1221 completed loading troops and cargo of units of the 1st Marine Division after having embarked 1,341 enlisted men and 61 officers.

[While Elmore did not transport K Company to Peleliu, other elements of the Corp's Third Battalion were onboard for the assault.]

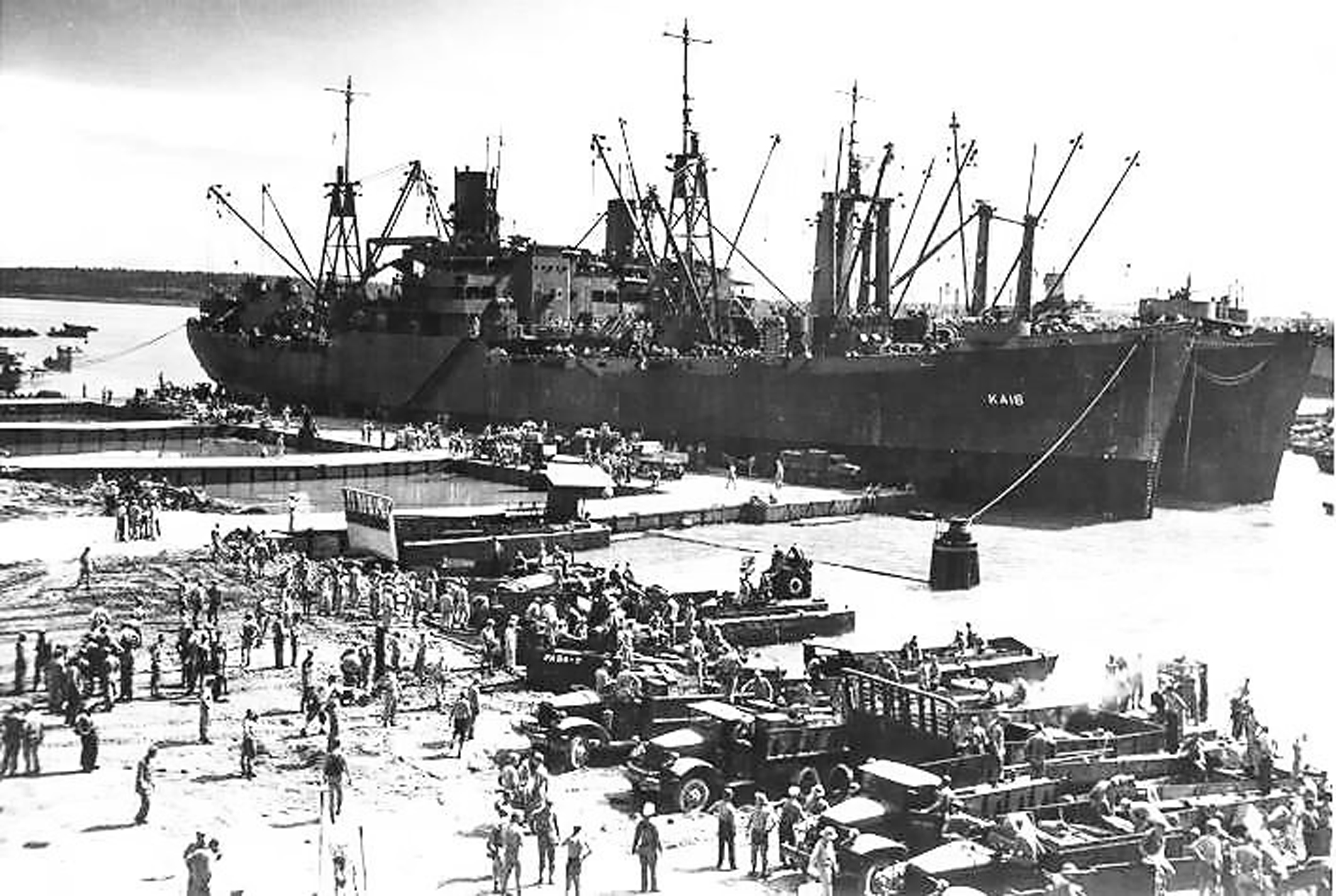

Marines waiting to board USS Elmore (APA-42), as noted by Sgt. R. V. Burgin in Islands of the Damned.

"Near the end of April, LCMs carried the First and Third battalions back down the coast to Borgen Bay. Ten days later, about the first of May, they started shipping units out on LSTs. On May 4, the Third Battalion mustered down at the beach and, after waiting around for an hour or so as usual, dragged ourselves aboard USS Elmore, an attack transport."

Onboard the Elmore, headed for Peleliu.

"So, we were at sea again. The scuttlebutt was already circulating a day or wo out when the USS Elmore’s loudspeaker squawked to life and confirmed the bad news. We weren’t going back to Australia. We would disembark at a place we’d never heard of – Pavuvu in the Russell Islands. "

Two of the key characters in The Pacific were Sgt. Burgin and Lt. "Hillbilly" Jones. They were transported on Elmore, singing at night from the deck of the ship.

"I had no trouble with other officers. Sledge, in his book With the Old Breed, was too hard on officers, in my opinion. But even Sledge liked Hillbilly Jones. We all liked Hillbilly. First Lieutenant Edward A. Jones had been with us on New Britain, and he would be with us on Peleliu, for a time. He was the most—I don’t know what the word is—disciplinary officer I was ever around. He wasn’t a horse’s patoot. He didn’t make up his own rules. He went by the book. His mind-set was, You’re a Marine, and you’re going to act like a Marine whether you’re in the States or out here in combat. That’s the way it’s going to be. Whenever we’d fall in for morning roll call, standing in ranks, he’d be out in front and he’d inspect the rifles. He’d spent five years as a seagoing Marine, so he was sharp. I mean he would pull that rifle—snap!—and twirl it—snap!—and it would come back to you—snap! He had it all. When you fell in, your collar was buttoned, your cuffs were buttoned. You stood erect. You didn’t slouch. You stood like a Marine. From reveille to recall in the afternoon he was as GI as they ever came, I’ll guarantee you. But after recall turned us loose at four o’clock, Hillbilly was a different human being. He’d wander down to our tents carrying the guitar he always had with him and sit around and we’d sing and shoot the bull all night. Coming over from New Britain, we’d gather around Hillbilly on the deck of the Elmore singing one song after another. 'Waltzing Matilda' was popular, from our stay in Melbourne. We sang 'Danny Boy,' and 'She’s Nobody’s Darling But Mine.' My own favorite was 'San Antonio Rose'.”

From the Elmore’s War Dairy for 4 May 1944:

Anchored Borgen Bay, New Britain, [Papua, New Guinea] with units of Task Unit 34.9.5. At 0045, completed discharging troops and cargo of units of the 40th Division U.S. Army, after having disembarked 488 men and 30 officers. At 1221 completed loading troops and cargo of units of the 1st Marine Division after having embarked 1,341 enlisted men and 61 officers.

It would appear that Elmore transported most, if not all, of the Marine Corps 3rd Battalion from Cape Gloucester, New Britain to Pavuvu in the Russell Islands. Elmore arrived at Pavuvu on 7 May and departed on 8 May 1944. This was four months before the invasion of Peleliu.

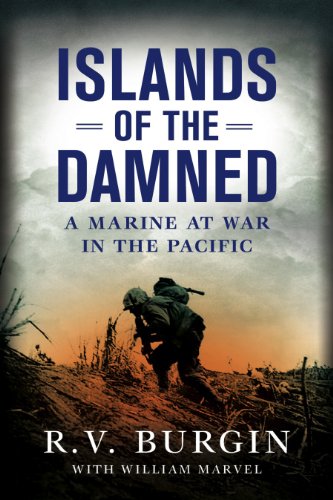

Palau Islands Map

| USS Aquarius (AKA-16) and USS Titania (AKA-13) unloading United States Marines at Pavuvu, Russell Islands, Solomon Islands, 28 Apr 1944 |

The Elmore’s Final Count:

The Battle of Peleliu lasted from 15 September until 27 November 1944. On the morning of September 15, the 1st Marine Division landed on the southwest corner of Peleliu.

Ferocious Japanese resistance inflicted heavy casualties on U.S. troops before the Americans were finally able to secure the island. The Battle of Peleliu resulted in the highest casualty rate of any amphibious assault in American military history. Of the approximately 28,000 Marines and infantry troops involved, a full 40 percent of the Marines and soldiers that fought for the island died or were wounded, for a total of some 9,800 men (1,800 killed in action and 8,000 wounded). Characteristically, the Japanese defenders refused to surrender, and virtually all of them were killed.

USS Elmore was part of the initial assault on 15 September 1944:

Arrived in Transport Area off Peleliu Island in the Palau Islands, Western Carolines. Commenced debarking troops and cargo of the 1st Marine Division for beach assault. Received casualties later in the day. A number of Marine casualties died onboard Elmore from their wounds and were buried at sea during this operation: three on 15 September, two on 16 September, two more on 17 September, another two on 18 September and one on 19 September. Transferred 30 casualties to HH-10 on 18 September. On 19 September, transferred 25 Marines, former casualties, to beach. One Marine died this date and was buried at sea. On 20 September, a seaman from USS Wayne (APA-54) died of wounds aboard and was buried at sea. On 21 September, 122 Casualties were transferred to the hospital ship USS Bountiful (AH-9). One additional Marine died this date and was buried at sea. On 22 September another Marine died and was buried at sea.

In sum, 14 men were buried at sea from the deck of Elmore. Elmore stayed at Peleliu until ordered to report to Hollandia, departing on 24 September 1944.

Click on a link below to learn more

No Pacific Paradise

No Pacific Paradise

By Richard B. Frank

Civilians and European-theater veterans thought of South Pacific island "rest areas" as enticing beaches; vivid, multi-hued blossoms amid lush, green flora and fauna; the pristine tints of a tropical sunset or sunrise; and perhaps fervid mental images of amorous entanglements with lithe and willing native damsels. They never heard of Pavuvu, the one six-letter obscenity in the lexicon of 1st Marine Division veterans of World War II.

The "straight scoop" rumor that swept the division's ranks on departure from New Britain affirmed a universe governed by a just moral order: The bedraggled unit was headed back to Melbourne. But instead of Melbourne—and justice—the 1st Marine Division got Pavuvu. The largest of the Russell Islands, it rests 60 miles north of Guadalcanal and measures at most 8 miles wide and 1,500 feet tall. A huge coconut plantation organized the island into symmetrical ranks of palms. It looked quite reasonable from the air—and it was from the air that staff officers of the III Amphibious Corps, to which the 1st Division had been assigned, picked Pavuvu, primarily because Guadalcanal was already crowded with American installations.

For four years those neat rows of palms had indiscriminately bombarded the ground with unharvested coconuts. The hairy, shelled missiles rotted and then dissolved under rains that continued far beyond nature's normal cycle in 1944 to turn the ground into a mush best navigated barefoot. For accommodations, the division was issued cots (frequently rotted) and pyramidal tents (still more frequently riddled with holes). Every imaginable material found employment in getting personal gear off the ground, but individual Marines learned that only coral gravel existed in enough quantity to floor most tents—after work details first paved company streets.

Initially there were no lights, no mess halls, and no recreation areas on Pavuvu, as well as no adequate supply of fresh food. The menu was officially called "B," which in fact was like a warmed version of "C" rations—the minimum sustenance. Bathing was done naked in the open with hopes both lathering and rinsing could be completed before the fickle rains that supplied the shower ended. The island also lacked adequate training space, particularly after firing ranges were established. Maneuvers of units larger than a company inevitably overlapped terrain occupied by some essential function created by the Marines.

Then there were the rats and land crabs. Rodent raiders seemed to mass at night for close-order drill across tent tops. When they became bored, they fell out with squeals to scamper down the sides and ropes. Great ingenuity went to devising means of rat control, from individual traps to on one occasion a mass flamethrower hunt. The rats at least evoked some grudging respect for their nerves and agility; the slimy land crabs provoked nothing but disgust.

"You could almost hear the noise that loneliness made as it came crashing through the grove at sunset," noted the division historian. Anyone who sought solitude at night was recognized as sick. Instead, with rituals that would have filled the notebooks of an eager anthropologist, Marines organized themselves into small groups of friends. The one great shared recreation was an ad hoc movie amphitheater. Hollywood's best and worst enjoyed equally avid attendees. When well-proportioned actresses appeared, the projectionists learned to halt the film and back it up to reshow the scene three and sometime four times.

Veterans retained just one joyful memory of Pavuvu: Comedian Bob Hope made an extraordinary effort to put on a show there for them they never forgot.

Source:

Naval History Magazine, April 2010

The Peleliu Death Trap

The Peleliu Death Trap

A renowned memoirist of Pacific war combat describes fighting in the desperate, hellish Battle of Peleliu, where "the whole island was a front line."

By Eugene B. Sledge

In September 1994, 13 years after Eugene Sledge's classic Marine war memoir, With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, was first published, Proceedings magazine published the following article in which the author describes his brutal baptism of fire.

The 1st Marine Division was ordered to seize Peleliu in the Palau Islands, to secure General Douglas MacArthur's right flank for his return to the Philippines. D-Day was 15 September 1944. Our commanding general predicted a three-day battle, a gross miscalculation. The Peleliu campaign turned into one of the bloodiest, most vicious battles of World War II.

I was a 60-mm mortarman in K Company, 3d Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment. 1st Marine Division, having joined the company as a replacement while the division was in rest camp on Pavuvu in the Russell Islands after the campaign at Cape Gloucester, New Britain. The division had fought the epic Battle of Guadalcanal prior to Cape Gloucester, so I became part of a proud, high-spirited, elite veteran outfit. Even so, it was made up of very young men. 85 percent had not become 21.

From June through August 1944, we trained hard in the use of all infantry weapons, tactics, and amphibious assault from amphibious tractors (amtracs) onto a strongly fortified beach. Efficiency and endurance were drilled into us. The veterans taught the replacements all the ins and outs of combat with a ruthless foe. We mastered our own weapons, studied those of the Japanese, and learned to distinguish their sounds.

All the while we led a Spartan existence. In our tent camp we battled Pavuvu's ubiquitous land crabs in our tents; huge rats climbed the palm trees where they thrashed around in the fronds with large fruit bats; the fight usually ended up on top of the tents. Mud was everywhere, and warmed-over C-rations and stale coffee passed for chow. For entertainment, we played baseball and volley ball, ran foot races, and sat on log seats in a coconut grove to watch old B-grade movies.

The high point was a visit by Bob Hope. Pavuvu was off the main routes to or from everywhere, and it was out of his way. But he wanted to put on a show for the 1st Marine Division. He never had a more appreciative audience. After we suffered such staggering casualties at Peleliu, Bob saw some of our wounded at a naval hospital in the States. One teenaged Marine turned to him and said, "Hey Bob, remember Pavuvu?" Hope later wrote that he got so choked up he could not go through the ward with its long rows of cots with all the Peleliu casualties. Years later, he said that, of all the thousands of shows he did for troops during his long career, the Pavuvu show was the most memorable. It certainly was wonderful for us. It was the last light-hearted moment many of my buddies had in their short lives.

We shipped out for Peleliu in late August. Each assault company boarded a tank landing ship (LST) with amtracs loaded in the tank deck. K Company, 5th Marines went aboard LST-661. Many dark stormy nights at sea, a buddy and I stood watch with one of the crew in a 40-mm bow gun tub. The convoy operated under radio silence, which meant the ships depended on their lookouts to help the conning officer maintain station. The Sailor had a sound-powered headphone set connected to the bridge. We crouched under our ponchos and helmet liners on each side of him as we strained our eyes for the stern of the LST dead ahead. During driving rain both ships were heaving up and down and wallowing in heavy seas (as only an LST could). One moment the stern of the ship ahead was barely visible, then, in the blinding rain and inky blackness, it would heave up out of the turbulent sea threatening to come crashing down on us. Inevitably it would slide on through the blackness as our hearts pounded, and the Sailor alerted the bridge. We thought of all those sleeping Sailors and Marines who, unknowingly, were depending on us. We knew that if a collision occurred we would never face disciplinary action because we would be killed instantly.

After our watch was relieved, we went shuddering and shaking to the galley for a cup of hot coffee. The stress would have put a civilian in the hospital.

The assault on Peleliu and capture of the beach was my baptism of fire, and a shock it was. Our amtracs, carrying about 20 Marines each, formed up into waves after leaving the LSTs. The prelanding bombardment had been in progress for some time; the noise was thunderous. We, not being fools, were all scared to death about landing on that Jap-held beach. The veterans because they knew what to expect, the new men because we didn't know what to expect. I didn't know how I would react under fire?nobody ever does until he has experienced the madness of front-line combat. I hung weakly to the side of the tractor and prayed that I would do my duty, survive, and not wet my pants.

We were in the second wave, and our amtrac engine idled as we awaited the signal to go in. As we waited, we marveled at the awesome power of the barrage by battleships, cruisers, destroyers, rocket firing LCIs, supported by Corsairs and dive-bombers strafing and bombing. The beach was a sheet of flame backed by a huge wall of black smoke, as though the island were on fire. The incredible power of the 16-inch salvos from the battlewagons was like nothing any of us had ever experienced. Even above the general din, we could distinguish the rumble of these huge shells as they tore toward the island. When they exploded, trees and debris were hurled high into the air. We had to shout to each other because of the tumult and cursed when the naval officer waved the flag for us to start in. The amtrac engines roared and we lurched forward. Everything my life had been before and has been after pales in the light of that awesome moment.

My heart pounded as we churned toward that inferno. For all too many young Americans, it was into oblivion, before they had ever really lived. The fleet moved to the flanks and continued to fire as the tractor formations started in. As we moved onto the reef (about 500 yards opposite Beach Orange 2), Jap shells came screaming into the tractor waves. The sound of an incoming artillery shell is one of the most gut-wrenching, unforgettable sounds of combat. The smaller the caliber of the gun, the higher the pitch. The farther away the gun, the longer the excruciating agony of the approach tortures the mind. I saw several amtracs hit. Some burst into flame, and bodies of Marines were blown into the air. Some Marines escaped from the disabled vehicles and suffered the horror of coming in against relentless enemy machine gun fire. I was sickened to see these helpless Marines slaughtered.

We hit a coral head and stalled for terrifying moments. Just as we started in again a huge shell came roaring in and exploded just off our bow. No damage was done, but had we not been slowed by the coral head, that Jap gunner would have hit us dead center. As it was, my heart nearly stopped. Every Marine in that amtrac was sickly white with terror. We got to the beach amid erupting shell bursts and the rattle of enemy machine gun bullets against the steel of our amtrac. Heavy Jap artillery and mortars were pounding the beach, and Marines were getting hit constantly. We piled out of our amtrac amid blue-white Japanese machine-gun tracers and raced inland a few yards.

I hit the deck near my squad mates. Back on the reef I saw burning amtracs and struggling Marines. I felt like weeping over their fate, but we were in a maelstrom of crashing shells and snapping rifle and machine-gun bullets. Our own lives hung by a thread. We were ordered off the deadly beach, and I glanced back at the spot our amtrac had just left. A DUKW (amphibious truck) came in and stopped there, to be hit almost instantly by a large shell that exploded dead center, engulfing it in thick black smoke. I didn't see anybody get out.

We raced inland into the cover of the scrub growth. The company advanced in extended order, stopping at intervals to clear out snipers, or Japs hiding in spider foxholes as they tried to fire at us. We reached our objective, the eastern shore, by afternoon. The heat was terrible, 110-115 degrees Fahrenheit. We were warned to conserve water. Some Marines suffered heat exhaustion and were evacuated. Most returned soon after. While on the eastern shore cliffs, we could see Japs swimming and running along the reef. We killed most of them.

A runner came up with orders to fall back because the Japs had gotten in our rear. The veterans griped bitterly at having to leave such "good shooting." We fell back to the edge of the airfield with L and I Companies in the vicinity, but the thick growth precluded solid contact. We had no contact with the 7th Marines on our right and the 2nd battalion, 5th Marines on our left. The company formed a firing line along a coral trail just within the scrub with good visibility of the airfield and Bloody Nose Ridge beyond. Snafu Shelton (a veteran) and I set up our 60-mm mortar in a shallow crater bordering the trail. Vehicles of some sort were racing across the open field toward our line on the left. "Snafu," I asked, "what are those amtracs doing out there in enemy territory?"

"Amtracs, hell," he snapped, "them's Nip tanks." I shuddered. "Stand by to repel counterattack," came the order. "Mortars stand by to fire."

R. V. Burgin, our squad leader and observer, turned around and yelled the range and direction to us. Snafu set the sight for range and windage. I readied a high-explosive shell. "Fire one!" yelled Snafu. I raised the shell with my left hand. Instantly a blast of .30-caliber machine-gun fire cracked just inches over my hand. The red tracers meant a U.S. gun, and it came from the rear.

"Goddamnit, fire, Sledgehammer!" repeated Snafu. I tried again with the same terrifying results and jerked my hand down. I had no desire to lose it or have that mortar shell explode and kill our squad. I looked to the rear and saw an American Sherman tank as it fired its 75-mm gun to our right around a bend in the trail. It was dueling with a 75-mm Jap field gun on the same trail we were on. We could not see the Japs for the scrub and the tanker mistook us for Jap infantry supporting the artillery piece. The smoke and dust from exploding shells in the area made his error understandable, but we realized that once he knocked out that Jap gun, he would swing his main gun on us and we would be dead.

Sergeant Hank Boyes ran back to the tank and identified us. The crew told him they were sure glad they hadn't hit any of us. Boyes got on the turret and directed their fire. In addition to the Jap gun around the bend, they knocked out three more 75s, all the while firing their machine guns in a complete circle. There never was a front line on Peleliu. The whole island was a front line.

All this time the tank battle on the left raged until all the enemy vehicles were destroyed. We were all pinned down during the whole affair. Hank was exposed the entire time on the Sherman tank. The Nips fired everything they had at him, but he didn't get a scratch. When it quieted down in our area, four Jap 75s and about 200 infantry had been accounted for. They had all been secreted in the scrub in ambush. Had it not been for Hank's heroic actions, K Company would have been annihilated that terrible day. He was awarded a Silver Star (it should have been the Medal of Honor) and was promoted to gunnery sergeant. He was later wounded, but recovered and served through the long ordeal on Okinawa. Boyes was dignified, modest, and soft spoken. Though a strict disciplinarian, he was fair. He lives in Australia now, but distance matters not. All of us love him like a brother.

Next morning we were ordered to capture the airfield, and we started across at a trot in the searing heat, into the face of Bloody Nose Ridge. That attack was the worst experience any of us had during all of World War II. The Nips smothered the open ground with artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire, and the company had to go about 200 yards through the thickest fire I ever saw. The ground rocked and swayed from shell concussions, and streams of machine-gun tracers streaked past our ears.

I expected to get hit any moment as I saw Marines crumple, pitch forward, or sag to the deck in death. I don't know how many losses any of the companies had, but it was an awful experience. Years later, a retired Marine Corps general who had witnessed the attack told me it was a foolish mistake by the division commander.

As we fought through that first week onto the ridges, we slowly realized that he had sent us into a death trap on Peleliu. Amphibious doctrine stated that the ratio of an assault force should be three-to-one over the defenders. The division's three infantry regiments (the 1st, 5th, and 7th Marines) each numbered about 3,000 infantrymen, excluding attached specialists who were not fighting infantry. We hit Peleliu with 9,000 Marine infantrymen. It was known that the Japs had more than 11,000 troops dug into those cement-hard coral ridges; rather than 3:1, we were outnumbered.

The 1st Marines were shot to pieces the first week, and I lost many a good friend. A note from the commanding general was read to all units on the line about D+5 or D+6, stating that we didn't need Army help to finish the job. It was met with curses and fervent hopes that the CG would burn in the nether regions. Fortunately, Major General Roy Geiger, the corps commander, ordered the CG to relieve the 1st Marines, and the 321st Infantry came to our aid. We were glad to see those dogfaces, and they did a good job.

The fighting in the ridges was exhausting and costly. Flamethrowers were indispensable. Any cave we attacked was covered by heavy Jap fire from other mutually supporting positions, and all were interconnected within the ridges. The Japs fought like demons, and shot our stretcher teams, the corpsmen and the wounded. We hated them with a passion known to few antagonists. Some writers blame it on racism. I don't believe that. The Code of Bushido by which the Japs fought fostered brutality. We never took prisoners, even when some few tried to give up. They often tried to throw a grenade at us. After taking a position we routinely shot both the dead and wounded enemy troops in the head, to make sure they were dead. Survival was hard enough in the infantry without taking chances being humane to men who fought so savagely.

The shell-blasted ridges took on the character of a moonscape. They were also a garbage dump, what with rotting enemy dead that we couldn't bury in the hard coral, discarded rations, and human excrement from thousands of men in a restricted area. The stench was nauseating. Huge green flies swarmed off Jap corpses and covered our C-rations. Too fat to be blown away, they had to be picked off. We covered our dead with ponchos and put them behind our positions. Our body filth from sweat, rain, and dust made us miserable, but it was unavoidable.

The Japs raided our lines every night but we always stopped them, though not before they caused casualties. The 1st Marine Division fought in this hell for 30 days and nights, and was shattered. It suffered 6,526 killed and wounded. My company sustained 64 percent casualties, including our beloved commander, Captain Andrew Haldane. The Jap garrison was all but wiped out; almost 11,000 were killed. Seven soldiers were captured and a few Korean laborers. It was all a criminal waste, because the island should have been bypassed. We realized that then, 50 years ago.

The awful struggle was a testament to the skill and bravery of the Marines against a tenacious foe. But our division intelligence section lacked critical information regarding:

• The large coral ridge complex, containing more than 500 connecting caves.

• The enemy plan to conserve manpower and fight a battle of attrition.

• Enemy plans for intensive night infiltration, greater than Marines had previously experienced.

There had never been anything like Peleliu in the Pacific. it set the stage for the bloodbaths of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. But they had strategic significance. As it turned out, MacArthur walked into the Philippines with little opposition. I shall always harbor a deep sense of bitterness and grief over the suffering and loss of so many fine Marines on Peleliu for no good reason. It was my privilege to fight alongside them, fine, courageous, loyal and dependable men who filled the ranks of the finest division in World War II.

We must never forget them.

Source:

Naval History Magazine, April 2010

Walking in My Father's Footsteps

Walking in My Father's Footsteps

By Henry Sledge

As a teenager, I would listen with rapt attention as my father, Eugene B. Sledge, recounted fighting the Japanese on Peleliu. I was always interested in his wartime experiences, and the thought of visiting the desolate, far-away island captivated me. While visiting my parents in the summer of 1999, Dad mentioned that the 55th anniversary of the Battle of Peleliu was approaching and a group of veterans and historians was going to the island. I then and there decided to see Peleliu for myself.

Visiting Orange Beach 2, where Dad landed in his LVT on D-day, was a visceral experience. I spent several minutes walking alone along the flat, sandy shore, making mental notes. The sand was clean, and the air, while characteristically hot and humid, smelled fresh.

The ground in the White Beach area, a few hundred yards north, was sharp coral. I thought about how the water, now so clear, ran red with Marine blood that day in 1944. Reaching down and touching the coral, I imagined hitting the deck to avoid enemy fire. It was easy to understand why the Marines' dungarees were torn and bloody after fighting in this environment. Just off the beaches the scrub growth began. While walking through it I looked down and saw an unexploded Japanese grenade. It was rusty, but completely intact.

At Peleliu's airfield, I found the area where my father's outfit, Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, crossed on the morning of D+1. Again I separated myself from the group. I wanted to be alone to reflect. My father's description of running across this shell-torn field in full battle gear was vivid in my mind. The Umurbrogol ridges several hundred yards to the north, where so much enemy fire originated, were obscured by heavy vegetation on the day of my visit, not blasted and burned bare by naval gunfire as they were during the battle.

Heavily used during the war, the airfield was abandoned and quiet in 1999, with weeds growing in patches through the dazzling white coral runway. I picked up a handful of that crushed coral and let it sift through my fingers as I thought about Dad and his buddies, crouched low, squinting against the bright glare, gritting their teeth, cursing the Japanese, clutching their carbines and rifles, and running as fast as they could. He always told me it was one of the more terrifying moments of the war for him, crossing this wide, open runway with shrapnel and tracer bullets snapping through the air.

While comparatively few Americans visit Peleliu, fewer still venture across the channel to Ngesebus Island. One of our group's main objectives that day was to find a particular Japanese bunker. We located it, overgrown with vegetation. Here Dad's 60-mm mortar section battled and killed the bunker's 17 defenders. A 75-mm shell hole in the bunker's side was still charred around the edges from where a flamethrower had finished off the Japanese inside.

At one end, from the same spot my father had stared down the muzzle of an enemy machine gun, I peered into the structure, only to see murky water and tangled roots. On the ground nearby lay some 60-mm mortar shells covered in thick green moss. At least some of them had to have been his. Before leaving the bunker, I used my machete to hack a chunk of mossy concrete from one of its walls. Now on my bookshelf, that piece of history serves to remind me that I've been to Peleliu, walked its hallowed ground, and seen the rusted remnants of my father's war.

Source:

Naval History Magazine, April 2010

No Enchanted Evenings in This Pacific Warfare

MIDWAY through the first hour of “Band of Brothers,” HBO’s 2001 mini- series about a company of paratroopers during and after D-Day, there’s a scene on a troop ship that’s jampacked with new recruits on their way to hard fighting in the European theater. “Right now some lucky bastard’s headed for the South Pacific,” one soldier says to another, envious. “He’s going to get billeted on some tropical island sitting under a palm tree with six naked native girls helping him cut up coconuts so he can hand-feed them to the flamingos.”

Now comes “The Pacific,” an HBO mini-series by Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks and the rest of the “Band of Brothers” crew that spends 10 grueling hours and almost $200 million showing just how inaccurate that newbie’s idyllic image was. The series, in one-hour episodes that begin next Sunday, follows three real-life Marines from Pearl Harbor to homecoming after V-J Day. There are no naked native girls or flamingos. Instead there are bloody battles against well-fortified enemies on small islands. There are heroic deaths and random ones; unrelenting rainstorms, tropical diseases, nervous breakdowns.

Mr. Spielberg, who was born in 1946, said the seed that became “The Pacific” was planted in his childhood, when he was confused by the disparity between the formulaic war films he would watch — central hero, romance, defining battlefield moment — and the stories he would hear from his father and an uncle, who both served in the Pacific.

“My uncle and my dad were telling me how hellacious the war was, and it just wasn’t jibing with what was coming out of Hollywood,” Mr. Spielberg said. Missing were the grind and harshness that the ground troops on the islands experienced — the malaria, hunger, extreme heat, sense of isolation — elements generally not captured by the films focused on Pearl Harbor, Midway and the Pacific’s other great battles.

After “Band of Brothers” came out — the series won six Emmy Awards — the mail told him he had to address this nagging incongruity. “All the letters that came from the veterans of the Pacific theater of operations were, ‘When are you going to tell our story?’ ” Mr. Spielberg said.

That story was of a war that many Americans could not fully visualize, then and now. The pivotal moments of the European war featured locales people had heard of and been to — the bombing of London, the liberation of Paris, and so on — and there was a central villain, Hitler, who was known to all. But the troops sent to try to stop the Japanese from taking over the South Pacific were, for the most part, going to obscure islands.

How obscure? Before 1940 Guadalcanal, site of the first major Allied initiative, had been mentioned by name in The New York Times only about a half-dozen times; several of those were from the 1890s and involved “Baron Henry Foullon von Norbeck, the Austrian scientist and explorer, who with several members of the party he was leading was killed and devoured last summer by the inhabitants of Guadalcanal.”

Even Mr. Hanks, a serious history buff, confessed that he knew nothing about Peleliu before beginning work on “The Pacific.” The battle for that island in the fall of 1944, which is the focus of Parts 6 and 7 of the mini- series, left more than 1,600 Americans dead and thousands more wounded.

If the Pacific war didn’t take hold in the popular imagination and Hollywood quite as firmly as the European one did, the roots may extend back to the coverage of combat in the two theaters. There were reporters in the Pacific, but certainly nothing like the 558 accredited print and radio correspondents covering the Normandy landings. Re-creating the sprawling, grueling story of the Pacific war was a matter of considerable research and synthesis. The process began shortly after the debut of “Band of Brothers” (like this series, a production of HBO, Mr. Spielberg’s DreamWorks and the production company of Mr. Hanks and Gary Goetzman, Playtone). The historian Stephen E. Ambrose, whose 1992 book had been the basis for that mini-series, had already been interviewing Pacific war veterans, collecting their stories.

“I suggested to Stephen that I’d be happy to pony up some cash and replace that tape recorder with a video camera,” Mr. Spielberg said, and the result was a substantial archive of firsthand accounts. (Hugh Ambrose became a historical consultant to the series after his father died in 2002.) The job of distilling that into a coherent narrative fell to a team of writers like Bruce C. McKenna.

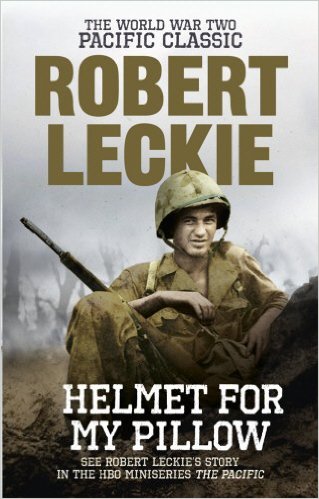

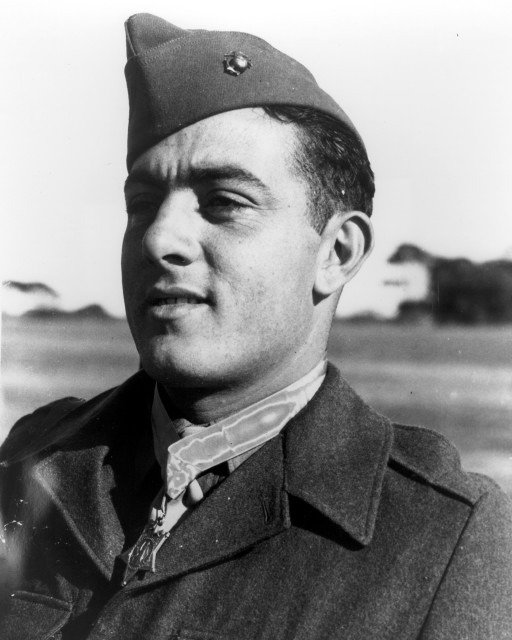

“All of us knew we had to do the whole war,” Mr. McKenna said; this would not be a simple story of a single battle. Eventually the decision was made to focus on three members of the First Marine Division: Eugene B. Sledge and Robert Leckie, both privates, and Sgt. John Basilone, who earned the Medal of Honor on Guadalcanal. Mr. Leckie and Mr. Sledge, who both died in 2001, wrote memoirs that became cornerstones for the series; Sergeant Basilone’s story was well documented in the news media at the time.

“We love the truth,” said Mr. Goetzman, who with Mr. Hanks also had success with the mini-series “John Adams,” another slice of history. “We think that’s where the best stories come from. You just can’t make up things that are any more exciting or any more compelling than what’s actually happened in this world.”

Combining the three men’s stories allowed Mr. McKenna and the other writers to take full advantage of the mini-series format, exploring their characters in a way that a standard two-hour war movie doesn’t allow. “What war movie have you ever seen where the main character was in a mental institute for half an episode?” Mr. McKenna said, a fate that befalls the Leckie figure. “And yet that’s a big part of war.” The physical and mental toll that the Pacific war took on the men who fought it is the mini-series’s defining feature.

“If ‘Band of Brothers’ was an examination of what we thought the Greatest Generation went through as a group, then this was more an examination of the personal cost to the individual,” said Tony To, who served as a co- executive producer on “The Pacific” and directed Part 6. Incongruously, that meant creating an even more expansive canvas than in “Band of Brothers,” in terms of both time and geography, to show the accumulation of pressures physical and psychological. (The writers used Sergeant Basilone’s return to the United States to sell war bonds as a way to break up the relentlessness of the battles.) It also meant few shortcuts.

For instance, Mr. To said, 500 coconut trees were brought to Australia, where the bulk of the filming was done, to create a particular setting; a less- conscientious production might have shot the actors in front of a blue screen and added the trees later. “We wanted the environment they were acting in to be as close as it could be to the actual experience,” Mr. To said, “so that they weren’t acting the experience, but actually experiencing it.”

Hawaii, Mr. To said, had been among the places in contention for the filming, but impediments like sacred burial grounds on the beaches there ultimately led the producers to select Australia instead. “We knew that whatever landscape we needed we would have to control completely,” he said, “because we were blowing it up,” not just once, but repeatedly: each island battleground had its own look (the black sand of Iwo Jima being particularly famous), so each required the beach on Australia’s northeast coast where the crew was working to get a makeover.

All these efforts represent an attempt to bring the starkness and psychological depth of the best Vietnam movies — “The Deer Hunter,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Platoon” — to the treatment of World War II. Mr. Spielberg and Mr. Hanks — one as director, the other as star — had already made strides in that direction in 1998 with “Saving Private Ryan,” whose unflinching depiction of the D-Day landing startled audiences. And where an earlier brand of ensemble World War II films — “The Dirty Dozen,” “The Great Escape” — were often star heavy, both “Band of Brothers” and “The Pacific” used actors with relatively low profiles.

Those actors — Joe Mazzello as Sledge, James Badge Dale as Leckie and Jon Seda as Basilone — knew early on that much would be asked of them.

They were sent to a simulated boot camp that entailed nine days of drilling and such, overseen by Capt. Dale Dye, a retired Marine. “We went into it thinking: ‘We’re actors. What can they really do?’ ” Mr. Mazzello said. “Well, we found out.”

Mr. Mazzello, a rather slender 24-year-old when the filming was taking place, said he lost 12 pounds during camp. (Though he also learned a lot: “You could show me a mortar from 1943. and I could still fire it.” The filming itself was no picnic either.

The battle scenes are, of course, filled with gunfire and explosions of all sorts, and there were no stunt doubles. But, Mr. To said, “we never asked our actors to do anything we wouldn’t do.” He recalled a scene in Episode 6 in which an explosion blows a soldier backward into a tree. To demonstrate the safety of the shot, Mr. To, the director of that episode, climbed into the harness and took the jolting ride.

All three lead actors spoke of developing an appreciation bordering on reverence for the men they were portraying. “We all felt a heavy responsibility in just needing to get it right,” Mr. Seda said. “We’re basically becoming the voices for all these men who never were able to truly express to their loved ones what they went through, and that’s a huge responsibility.”

One of those men, R. V. Burgin, 87, who fought in battles including New Britain, Peleliu (“by far the worst”) and Okinawa, had what is surely a veteran’s highest praise for the parts of the mini-series he had seen: “It puts you right in the foxhole with them,” he said. Mr. Burgin, who describes his war experiences in a new book, “Islands of the Damned: A Marine at War in the Pacific” (New American Library Caliber), recalled a request he made to Hugh Ambrose when he was interviewed for the series in 2004: “I told him, ‘Will you do me and all the rest of the guys out there who fought in that war a favor?’ And he said, ‘What’s that?’ And I said, ‘Leave the damn fiction out of it.’ ” The real stories of valor and loss, Mr. Burgin said, provide more than enough fuel for any mini-series.

There are, of course, innumerable stories out there still waiting to be told. Is Mr. Spielberg prepared for a new batch of mail after “The Pacific” is shown, from pilots, corpsmen, intelligence experts, Rosie the Riveters?

“All I can say is, please bring on the letters, because your first batch of letters led to this series,” he said.

SOURCE: New York Times

March 5, 2010

By Neil Genzlinger

7 Surprising Facts About the HBO Miniseries The Pacific

1. The Pacific is based on the stories shared in the real memoirs of U.S. Marines Eugene Sledge and Robert Leckie, both of whom are characters in miniseries.

Though a miniseries of its own, The Pacific was created as a companion to another popular wartime miniseries by HBO: Band of Brothers, which premiered in 2001 and focused on World War II. The Pacific presents the stories of three U.S. Marine Corps members – Eugene Sledge, Robert Leckie, and John Basilone – and their experiences in the Pacific Theater of Operations during the Pacific War.

Though these three men were each in a different regiment of the 1st Marine Division, their stories are drawn together thanks to their memoirs. The events of the miniseries come from With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa by Eugene Sledge and Helmet for My Pillow by Robert Leckie. Each memoir and the miniseries touches on the battles the 1st Marine Division and its men encountered, from Guadalcanal and Peleliu to the Battle of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

2. Although the miniseries itself was based on memoirs, HBO commissioned a book based on the series after it’s successful premiere.

There seemed to be no need for a companion novel for The Pacific – after all, the miniseries took its material from the books mentioned above – but ironically, when the show proved successful, HBO commissioned an entirely new book. However, to make the new tie-in book for the miniseries different and exciting for readers, HBO chose to incorporate a few new characters.

The book does cover the stories of John Basilone and Eugene Sledge but introduces Austin Shofner and Vernon Micheel. Written by Hugh Ambrose, a historian and the son of the author of the Band of Brothers tie-in book, the new characters help broaden the focus of the book’s stories to include more events during the Pacific War, including the fall of the Philippines, Midway, and Luzon.

3. Though the original battles featured in the miniseries weren’t fought in Australia, the country served as the filming location for all of the show’s scenes.

The Pacific may feature historical events that played out in the actual Pacific, but the miniseries wasn’t filmed in any of the original sites. Instead, the entire show was filmed in various locations throughout Australia. This was due to two companies associated with the series’ production, Seven Network, and Sky Movies. Both Seven Network and Sky Movies joined The Pacific in order to secure the necessary rights to air the finished show in Australia and the United Kingdom. So, the show’s production set up its headquarters in Melbourne and began casting and preparing for filming.

From August 2007 to May 2008, the cast and crew shot scenes at a wide variety of locations throughout Australia. National parks, downtown Melbourne, the beaches of Queensland, the suburbs, high schools and colleges, plantations, sand quarries, and even rural sites in Victoria were all used. Only one studio was used during the filming process, Central City Studios at Melbourne Docklands; all other shots were done on location.

4. The Pacific blew its budget; originally, $100 million was the production budget, but the miniseries ended up costing a total of $200 million.

Before production and filming began, producers estimated that The Pacific would cost about $100 million. However, it quickly exceeded that estimate and reached more than $200 million spent – and the miniseries earned itself the title of most expensive television miniseries ever created.

Steven Spielberg, known for his multimillion-dollar productions, spared no expense to recreate historically accurate battle scenes in “The Pacific.” The filming of the landing on the island of Peleliu cost $5 million. The scene required 300 actors to stay on an Australian beach for four days.

5. John Basilone really did participate in bond tours back in America – and he did reenlist in order to join his former friends at Iwo Jima.

Although The Pacific blends together the real stories of those who fought as Marines with fiction created by show runners, there was truth at the heart of the characters’ stories. One, in particular, John Basilone, had a story that seemed almost entirely fiction.

According to the miniseries, Basilone received a Medal of Honor for his heroism during the landing at Guadalcanal, then spent months celebrating his new status as a military hero traveling throughout the U.S. on a star-studded war-bond tour – only to reenlist so he can join the men of his company at Iwo Jima. There’s no fiction in Basilone’s story; every one of these moments are featured in the TV series is true.

Basilone did earn the Medal of Honor and returned to America in 1943, embarking on war bond tours that were publicized nationwide and celebrated with parades and audiences of thousands. He was recognized as a hero by celebrities, politicians, and national news outlets, and Basilone used his new-found fame to raise money for the war effort.

Unsurprisingly, this fame became too uncomfortable for the veteran, and he wanted to step out of the limelight – Basilone felt more at home on the battlefield. He asked the Marine Corps to return to war but was denied and offered an instructor position in the U.S. instead. Basilone refused, and made a second request; the Marine Corps approved this time, and Basilone reenlisted just in time to fight with his original company at Iwo Jima.

6. It was so realistic that some veterans who fought in the depicted battles fell into flashbacks.

Television shows tend to glamorize everything; such wasn’t the case with The Pacific. Veterans of the Pacific War found the miniseries to be so accurate, so realistic in its depiction of the battles that they felt as though they were back in those very moments. According to an opinion piece written by veteran Bill Gallo for NY Daily News, The Pacific and its visually stunning scenes were enough to bring on flashbacks.

Gallo stated that “it was real, so goddamned real that my head darted back to when I was wearing green combat fatigues and carrying my M-1 Garand rifle fighting in the Pacific.” Watching each episode of the series brought Gallo back to every battle he faced in the Pacific War, giving him flashbacks. For him, it brought back, the intensity of the situations and “the elements of war” as the show addressed his real-life experiences.

7. Executive producers Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks decided to create this miniseries, not because of the success of Band of Brothers; vets from the wars in the Pacific actually pleaded with the two to share their stories, their experiences.

Although Band of Brothers saw immense success after its premiere, that initial miniseries wasn’t what prompted Spielberg and Hanks to create a follow-up to capitalize on veterans’ stories. In fact, the inspiration for The Pacific sprung from veterans themselves; those who fought in the Pacific War reached out to the two executive producers and asked for their stories to be told.

Many of these veterans felt that Americans were very familiar with World War II, but were unaware of what took place in the Pacific. The story of the Pacific War was so drastically different from World War II, and a “particular kind of hell” according to those who fought its battles; they wanted to share their experiences before losing them entirely.

While The Pacific may appear as another war miniseries, another attempt to explain and summarize the events of an international conflict, it’s a show that does so much more. From introducing new audiences and new generations to the Pacific War to relaying the experiences of the Marine Corps and its men in brilliant, realistic detail, the miniseries presents an eye-opening view of what happened on the ground during the war.

Whether you’re watching The Pacific for the very first time, or it’s become your favorite since its premiere, there’s a lot to learn in each episode of this interesting and engaging show.

Source:

warhistoryonline.com

The Battle of Peleliu

US Marines during the Battle of Peleliu, 1944.

by Kennedy Hickman

Updated January 02, 2019

The Battle of Peleliu was fought September 15 to November 27, 1944, during World War II (1939-1945). Part of the Allies' "island-hopping" strategy, it was believed that Peleliu needed to be captured before operations could commence against either the Philippines or Formosa. While planners had originally believed that the operation would only require a few days, it ultimately took over two months to secure the island as its nearly 11,000 defenders retreated into a system of interconnected bunkers, strong points, and caves. The garrison exacted a heavy price on the attackers and the Allied effort quickly became a bloody, grinding affair. On November 27, 1944, after weeks of bitter fighting, Peleliu was declared secure.

Background

Having advanced across the Pacific after victories at Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, Guam, and Tinian, Allied leaders reached a crossroads regarding future strategy. While General Douglas MacArthur favored advancing into the Philippines to make good his promise to liberate that country, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz preferred to capture Formosa and Okinawa, which could serve springboards for future operations against China and Japan.

Flying to Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt met with both commanders before ultimately electing to follow MacArthur's recommendations. As part of the advance to the Philippines, it was believed that Peleliu in the Palau Islands needed to be captured to secure the Allies' right flank (Map).

The Allied Plan

Responsibility for the invasion was given to Major General Roy S. Geiger's III Amphibious Corps and Major General William Rupertus's 1st Marine Division was assigned to make the initial landings. Supported by naval gunfire from Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf's ships offshore, the Marines were to assault beaches on the southwest side of the island.

Going ashore, the plan called for the 1st Marine Regiment to land to the north, the 5th Marine Regiment in the center, and the 7th Marine Regiment in the south. Hitting the beach, the 1st and 7th Marines would cover the flanks as the 5th Marines drove inland to capture Peleliu's airfield. This done, the 1st Marines, led by Colonel Lewis "Chesty" Puller were to turn north and attack the island's highest point, Umurbrogol Mountain. In assessing the operation, Rupertus expected to secure the island in a matter of days.

Colonel Lewis "Chesty" Puller, 1950, US Marine Corps.

A New Plan

The defense of Peleliu was overseen by Colonel Kunio Nakagawa. Following a string of defeats, the Japanese began to reassess their approach to island defense. Rather than attempting to halt Allied landings on the beaches, they devised a new strategy which called for islands to be heavily fortified with strong points and bunkers.

These were to be connected by caves and tunnels which would allow troops to be safely shifted with ease to meet each new threat. To support this system, troops would make limited counterattacks rather than the reckless banzai charges of the past. While efforts would be made to disrupt enemy landings, this new approach sought to bleed the Allies white once they were ashore.

The key to Nakagawa's defenses were over 500 caves in the Umurbrogol Mountain complex. Many of these were further fortified with steel doors and gun emplacements. At the north of the Allies' intended invasion beach, the Japanese tunneled through a 30-foot high coral ridge and installed a variety of guns and bunkers. Known as "The Point," the Allies had no knowledge of the ridge's existence as it did not show on existing maps.

In addition, the island's beaches were heavily mined and strewn with a variety of obstacles to hamper potential invaders. Unaware of the change in Japanese defensive tactics, Allied planning moved forward as normal and the invasion of Peleliu was dubbed Operation Stalemate II.

A Chance to Reconsider

To aid in operation, Admiral William "Bull" Halsey's carriers commenced a series of raids in the Palaus and Philippines. These met little Japanese resistance led him to contact Nimitz on September 13, 1944, with several suggestions. First, he recommended that the attack on Peleliu be abandoned as unneeded and that the assigned troops be given to MacArthur for operations in the Philippines.

He also stated that the invasion of the Philippines should begin immediately. While leaders in Washington, DC agreed to move up the landings in the Philippines, they elected to push forward with the Peleliu operation as Oldendorf had begun the pre-invasion bombardment on September 12 and troops were already arriving in the area.

Going Ashore

As Oldendorf's five battleships, four heavy cruisers, and four light cruisers pounded Peleliu, carrier aircraft also struck targets across the island. Expending a massive amount of ordnance, it was believed that the garrison was completely neutralized. This was far from the case as the new Japanese defense system survived nearly untouched. At 8:32 AM on September 15, the 1st Marine Division began their landings.

The first wave of LVTs moves toward the invasion beaches, passing through the inshore bombardment line of LCI gunboats. Cruisers and battleships are bombarding from the distance. The landing area is almost totally hidden in dust and smoke.

Coming under heavy fire from batteries at either end of the beach, the division lost many LVTs (Landing Vehicle Tracked) and DUKWs forcing large numbers of Marines to wade ashore. Pushing inland, only the 5th Marines made any substantial progress. Reaching the edge of the airfield, they succeeded in turning back a Japanese counterattack consisting of tanks and infantry (Map).

A Bitter Grind

The next day, the 5th Marines, enduring heavy artillery fire, charged across the airfield and secured it. Pressing on, they reached the eastern side of the island, cutting off the Japanese defenders to the south. Over the next several days, these troops were reduced by the 7th Marines. Near the beach, Puller's 1st Marines began attacks against The Point. In bitter fighting, Puller's men, led by Captain George Hunt's company, succeeded in reducing the position.

Despite this success, the 1st Marines endured nearly two days of counterattacks from Nakagawa's men. Moving inland, the 1st Marines turned north and began engaging the Japanese in the hills around Umurbrogol. Sustaining serious losses, the Marines made slow progress through the maze of valleys and soon named the area "Bloody Nose Ridge."

As the Marines ground their way through the ridges, they were forced to endure nightly infiltration attacks by the Japanese. Having sustained 1,749 casualties, approximately 60% of the regiment, in several days fighting, the 1st Marines were withdrawn by Geiger and replaced with the 321st Regimental Combat Team from the US Army's 81st Infantry Division. The 321st RCT landed north of the mountain on September 23 and began operations.

A U.S. Marine Corps Chance Vought F4U-1 Corsair aircraft attacks a Japanese bunker at the Umurbrogol mountain on Peleliu with napalm bombs.

Supported by the 5th and 7th Marines, they had a similar experience to Puller's men. On September 28, the 5th Marines took part in a short operation to capture Ngesebus Island, just north of Peleliu. Going ashore, they secured the island after a brief fight. Over the next few weeks, Allied troops continued to slowly battle their way through Umurbrogol.

With the 5th and 7th Marines badly battered, Geiger withdrew them and replaced them with the 323rd RCT on October 15. With the 1st Marine Division fully removed from Peleliu, it was sent back to Pavuvu in the Russell Islands to recover. Bitter fighting in and around Umurbrogol continued for another month as the 81st Division troops struggled to expel the Japanese from the ridges and caves. On November 24, with American forces closing in, Nakagawa committed suicide. Three days later, the island was finally declared secure.

Aftermath

One of the costliest operations of the war in the Pacific, the Battle of Peleliu saw Allied forces sustain 2,336 killed and 8,450 wounded/missing. The 1,749 casualties sustained by Puller's 1st Marines nearly equaled the entire division's losses for the earlier Battle of Guadalcanal. Japanese losses were 10,695 killed and 202 captured. Though a victory, the Battle of Peleliu was quickly overshadowed by the Allied landings on Leyte in the Philippines, which commenced on October 20, as well as the Allied triumph at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

The battle itself became a controversial topic as Allied forces took severe losses for an island that ultimately possessed little strategic value and was not used to support future operations. The new Japanese defensive approach was later used at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In an interesting twist, a party of Japanese soldiers held out on Peleliu until 1947 when they had to be convinced by a Japanese admiral that the war was over.

Source: thoughtco.com

World War II: Battle of Peleliu

Video Clips from "The Pacific"

Artwork from "The Pacific"