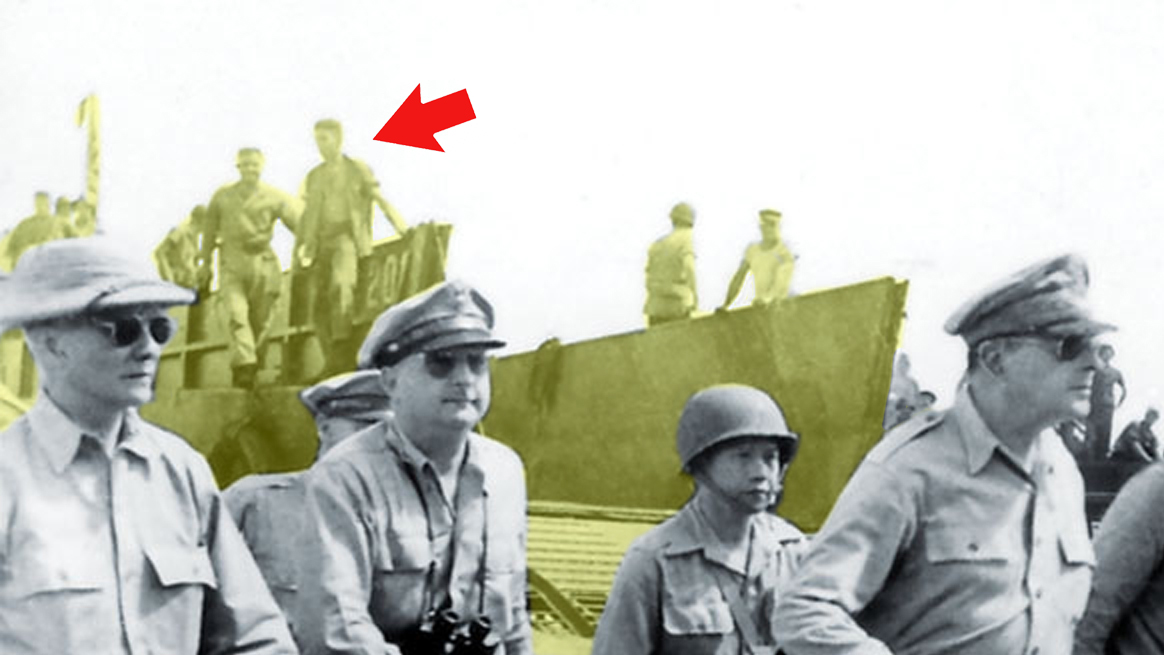

See above. The famous photograph of MacArthur's returns to the Philippines.

Pictured left to right:

Philippine President Sergio Osmeña, General George C. Kenney (almost completely hidden), Colonel Courtney Whitney, Philippine Army Brigadier General Carlos Romulo, General Douglas MacArthur, Lt. General Richard K. Sutherland, CBS correspondent Bill Dunn, and Staff Sergeant Francisco Salveron wade ashore just south of Tacloban at Palo, Leyte, October 20, 1944.

MacArthur's Return to the Philippines

Take a closer look. USS Elmore was there when MacArthur waded ashore at Palo (Red) Beach.

The landing craft immediately behind General MacArthur and his staff (highlighted in yellow) is a landing craft from USS Elmore (APA-42). As landing craft from the same ship would land together at an enemy beach, the adjacent landing craft are also from Elmore.

The sailor with the open shirt (indicated by the red arrow, below) has been identified as Carl J. Mullen, a Motor Machinist's Mate, 2nd Class, and member of the Elmore's crew. His son, Dick Mullen, confirms his father's identity in the photo.

Carl Mullen was well over 6', quite tall for that era. It shows in the photo above. Below is a portrait of Carl J. Mullen, a witness to one of the most significant historical events of the Pacific campaign.

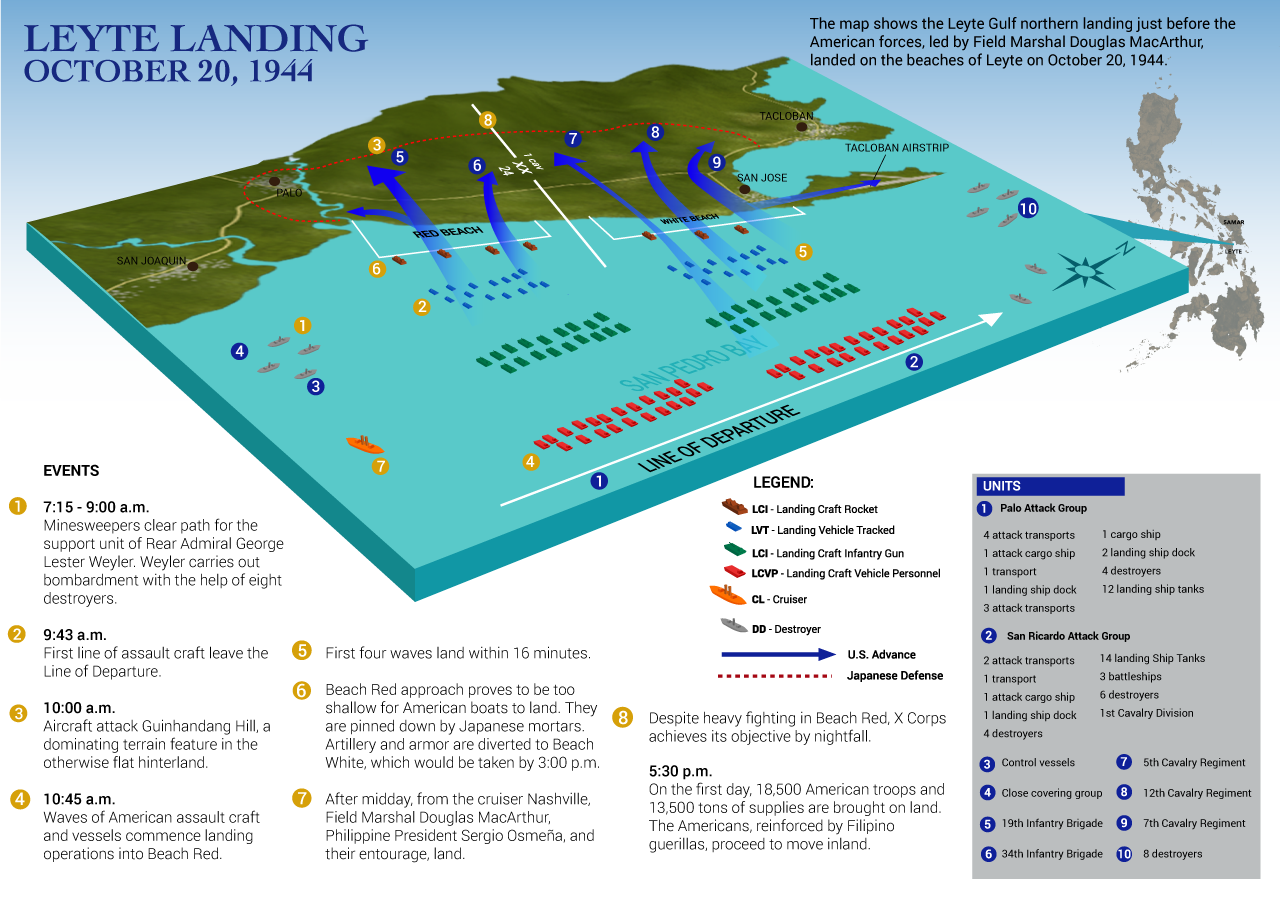

Along with USS Elmore (APA-42), the following ships were also assigned to the Palo Attack Group (Red Beach): attack transports USS DuPage (APA-41), USS Fuller (APA-7), and USS Wayne (APA-54); attack cargo ship USS Aquarius (AKA-16); transport USS John Land (AP-167); and Landing Ship, Dock, USS Gunston Hall (LSD-5). Click on map to enlarge image.

General MacArthur: “I have returned” to the Philippines

Landing barges loaded with troops sweep toward the beaches of Leyte Island as American and Jap planes duel to the death overhead. Troops watch the drama being written in the skies as they approach the hellfire on the shore. (20 October 1944)

Click on photos to zoom

American troops of Troop E, 7th Cavalry Regiment, advance towards San Jose on Leyte Island, Philippine Islands. (20 October 1944)

In March 1942 the Unites States forces on the Philippines had fought a bloody but unsuccessful action against the Japanese invasion. Famously when General MacArthur had then been compelled to evacuate the islands he had declared that “I will return”. Now that US forces were again landing on the Philippines he was not going to let the occasion go without publicity.

General Valdes accompanied General MacArthur and Philippine President Osmeña onto the landing beaches:

Entered Leyte Gulf at midnight. Reached our anchorage at 7 a.m. The battleships, cruisers, and destroyers opened fire on the beaches and finished the work begun two days before ‘A Day’ by other U.S Navy units. The boys in my ship where ready at 9:45 a.m. At 10 a.m. sharp they went down the rope on the side of the ship. Their objective was Palo.

At 1 p.m. General MacArthur and members of his staff, President Osmeña, myself, General Romulo, and Captain Madrigal left the ship and proceeded on an L.C.M for Red beach. The beach was not good, the landing craft could not make the dry beach and we had to wade through the water beyond our knees.

We inspected the area, and at two instances shots were fired by Japanese snipers. General MacArthur and President Osmeña spoke in a broadcast to the U.S. We returned to the ship at 6 p.m. under a torrential rain. We transferred to the Auxiliary cruiser Blue Ridge flagship of Admiral Barbey, as the SS John Land was leaving for Hollandia

MacArthur was now able to declare “I Have Returned”. In a speech, delivered via radio message from a portable radio set at Leyte, on October 20, 1944 he sent this message:

This is the Voice of Freedom,

General MacArthur speaking.

People of the Philippines: I have returned.

By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil – soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come, dedicated and committed to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring, upon a foundation of indestructible strength, the liberties of your people.

At my side is your President, Sergio Osmena, worthy successor of that great patriot, Manuel Quezon, with members of his cabinet. The seat of your government is now therefore firmly re-established on Philippine soil.

The hour of your redemption is here. Your patriots have demonstrated an unswerving and resolute devotion to the principles of freedom that challenges the best that is written on the pages of human history.

I now call upon your supreme effort that the enemy may know from the temper of an aroused and outraged people within that he has a force there to contend with no less violent than is the force committed from without.

Rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on. As the lines of battle roll forward to bring you within the zone of operations, rise and strike!

For future generations of your sons and daughters, strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike!

Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of Divine God points the way. Follow in His name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory!

Source: World War II Today (20 October 1944)

The Iconic Photograph

Iconic photos often have their own stories—some real, some myth.

For more than 70 years, questions have swirled around the famous photos of General Douglas MacArthur’s beach landings—first on Leyte, then on Luzon—as American troops returned to liberate the Philippines. Stories persist that MacArthur, no stranger to controversy or drama, staged the photos by coming ashore several times until the cameraman got the perfect shot, or that the photos were posed days after the actual landings. Those who were present say neither of these oft-repeated stories is true. But what really happened is even stranger than these misguided rumors.

MacArthur’s return was the high point of his war. In July 1941 he had been named commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, including all American and Filipino troops in the Philippines. In March 1942, with Japanese forces tightening their grip around the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered out of the islands for Australia. After reaching his destination, he vowed to liberate the Philippines, famously proclaiming, “I shall return.”

By April 1942, Japanese units advancing across the Philippines forced beleaguered Allied troops there to surrender. From then on, the Philippines “constituted the main object of my planning,” MacArthur said. By late 1944 he was poised to fulfill his promise—until an interservice battle threatened to derail his plans.

The U.S. Navy wanted American forces to bypass the Philippines and invade Formosa (now Taiwan) instead. MacArthur objected strenuously, both on strategic grounds and upon his belief that the United States had a moral duty to the people of the Philippines. The dispute went all the way up to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who ultimately sided with MacArthur.

Finally, on October 20, 1944, MacArthur made his long-anticipated return. At 10 a.m., his troops stormed ashore on Leyte, an island in the central Philippines. The heaviest fighting took place on Red Beach, but by early afternoon, MacArthur’s men had secured the area. Secured, however, did not mean safe. Japanese snipers remained active while small-arms and mortar fire continued throughout the day. Hundreds of small landing craft clogged the beaches, but the water was too shallow for larger landing craft to reach dry land.

Aboard the USS Nashville two miles offshore, a restless MacArthur could not wait to put his feet back on Philippine soil. At 1 p.m., he and his staff left the cruiser to take the two-mile landing craft ride to Red Beach. MacArthur intended to step out onto dry land, but soon realized their vessel was too large to advance through the shallow depths near the coastline. An aide radioed the navy beachmaster and asked that a smaller craft be sent to bring them in. The beachmaster, whose word was law on the invasion beach, was too busy with the chaos of the overall invasion to be bothered with a general, no matter how many stars he wore. “Walk in—the water’s fine,” he growled.

The bow of the landing craft dropped and MacArthur and his entourage waded 50 yards through knee-deep water to reach land.

Major Gaetano Faillace, an army photographer assigned to MacArthur, took photos of the general wading ashore. The result was an image of a scowling MacArthur, jaw set firmly, with a steel-eyed look as he approached the beach. But what may have appeared as determination was, in reality, anger. MacArthur was fuming. As he sloshed through the water, he stared daggers at the impudent beachmaster, who had treated the general as he probably had not been treated since his days as a plebe at West Point. However, when MacArthur saw the photo, his anger quickly dissipated. A master at public relations, he knew a good photo when he saw one.

Still, rumors persisted that MacArthur had staged the Leyte photo. CBS radio correspondent William J. Dunn, who was on Red Beach that day, hotly disputed these rumors, calling them “one of the most ludicrous misconceptions to come out of the war.” The photo was “a one-time shot” taken within hours of the initial landing, Dunn said, not something repeated sometime later for the perfect picture. MacArthur biographer D. Clayton James agreed, noting that MacArthur’s “plans for the drama at Red Beach certainly did not include stepping off in knee-deep water.”

Source: historynet.com

This story was originally published in the January/February 2017 issue of World War II magazine.

MacArthur Returns

After advancing island by island across the Pacific Ocean, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur wades ashore onto the Philippine island of Leyte, fulfilling his promise to return to the area he was forced to flee in 1942.

The son of an American Civil War hero, MacArthur served as chief U.S. military adviser to the Philippines before World War II. The day after Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, Japan launched its invasion of the Philippines. After struggling against great odds to save his adopted home from Japanese conquest, MacArthur was forced to abandon the Philippine island fortress of Corregidor under orders from President Franklin Roosevelt in March 1942. Left behind at Corregidor and on the Bataan Peninsula were 90,000 American and Filipino troops, who, lacking food, supplies, and support, would soon succumb to the Japanese offensive.

After leaving Corregidor, MacArthur and his family traveled by boat 560 miles to the Philippine island of Mindanao, braving mines, rough seas, and the Japanese navy. At the end of the hair-raising 35-hour journey, MacArthur told the boat commander, John D. Bulkeley, “You’ve taken me out of the jaws of death, and I won’t forget it.” On March 17, the general and his family boarded a B-17 Flying Fortress for northern Australia. He then took another aircraft and a long train ride down to Melbourne. During this journey, he was informed that there were far fewer Allied troops in Australia than he had hoped. Relief of his forces trapped in the Philippines would not be forthcoming. Deeply disappointed, he issued a statement to the press in which he promised his men and the people of the Philippines, “I shall return.” The promise would become his mantra during the next two and a half years, and he would repeat it often in public appearances.

For his valiant defense of the Philippines, MacArthur was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and celebrated as “America’s First Soldier.” Put in command of Allied forces in the Southwestern Pacific, his first duty was conducting the defense of Australia. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Bataan fell in April, and the 70,000 American and Filipino soldiers captured there were forced to undertake a death march in which at least 7,000 perished. Then, in May, Corregidor surrendered, and 15,000 more Americans and Filipinos were captured. The Philippines were lost, and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff had no immediate plans for their liberation.

After the U.S. victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, most Allied resources in the Pacific went to U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz, who as commander of the Pacific Fleet planned a more direct route to Japan than via the Philippines. Undaunted, MacArthur launched a major offensive in New Guinea, winning a string of victories with his limited forces. By September 1944, he was poised to launch an invasion of the Philippines, but he needed the support of Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet. After a period of indecision about whether to invade the Philippines or Formosa, the Joint Chiefs put their support behind MacArthur’s plan, which logistically could be carried out sooner than a Formosa invasion.

On October 20, 1944, a few hours after his troops landed, MacArthur waded ashore onto the Philippine island of Leyte. That day, he made a radio broadcast in which he declared, “People of the Philippines, I have returned!” In January 1945, his forces invaded the main Philippine island of Luzon. In February, Japanese forces at Bataan were cut off, and Corregidor was captured. Manila, the Philippine capital, fell in March, and in June MacArthur announced his offensive operations on Luzon to be at an end; although scattered Japanese resistance continued until the end of the war, in August. Only one-third of the men MacArthur left behind in March 1942 survived to see his return. “I’m a little late,” he told them, “but we finally came.”

Source: history.com

Original Published Date: July 21, 2010

Last Updated: July 28, 2019