Leyte Landing: 20 October 1944

Top Layer

General MacArthur wades ashore at Red Beach

Bottom Layer

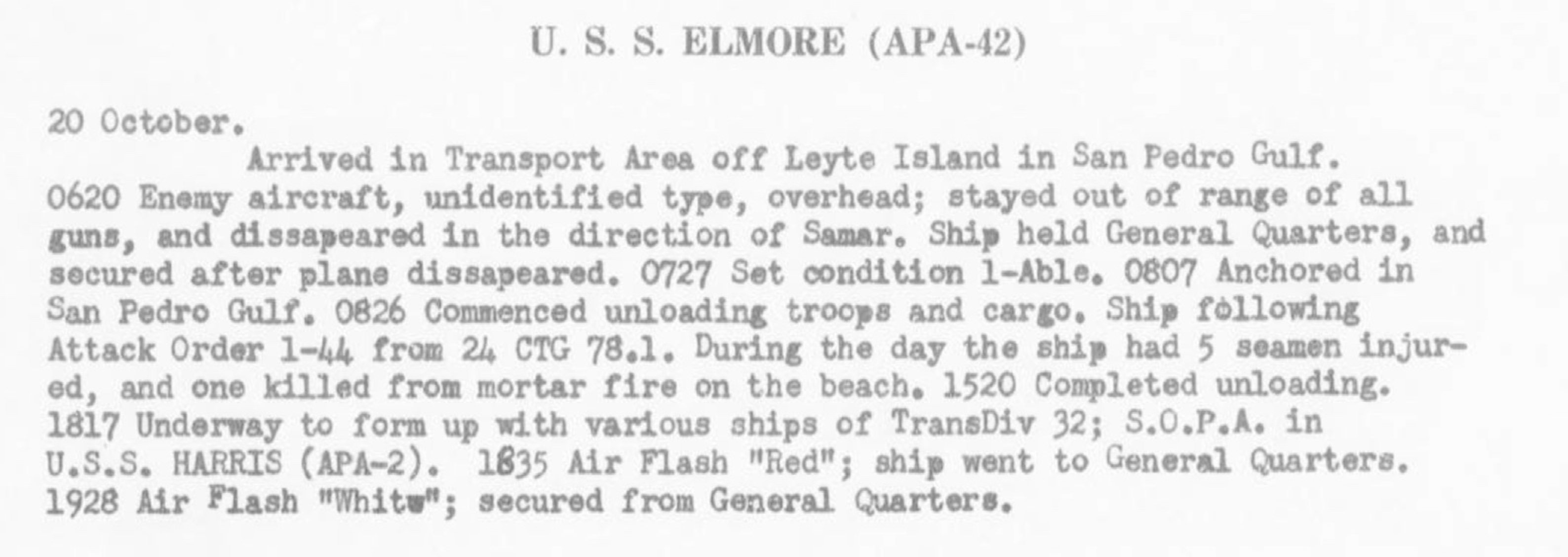

A Difficult Day for USS Elmore

Overview

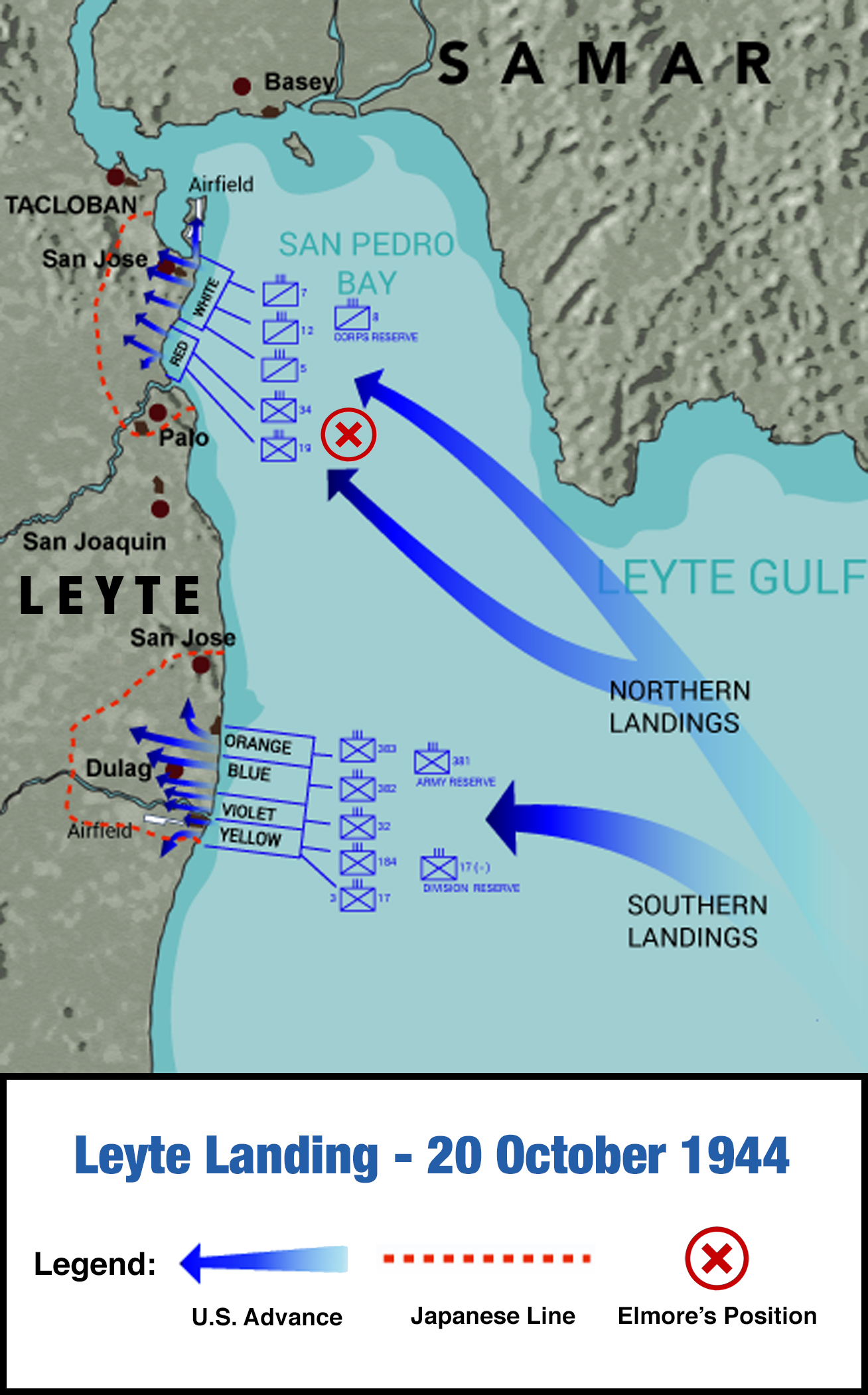

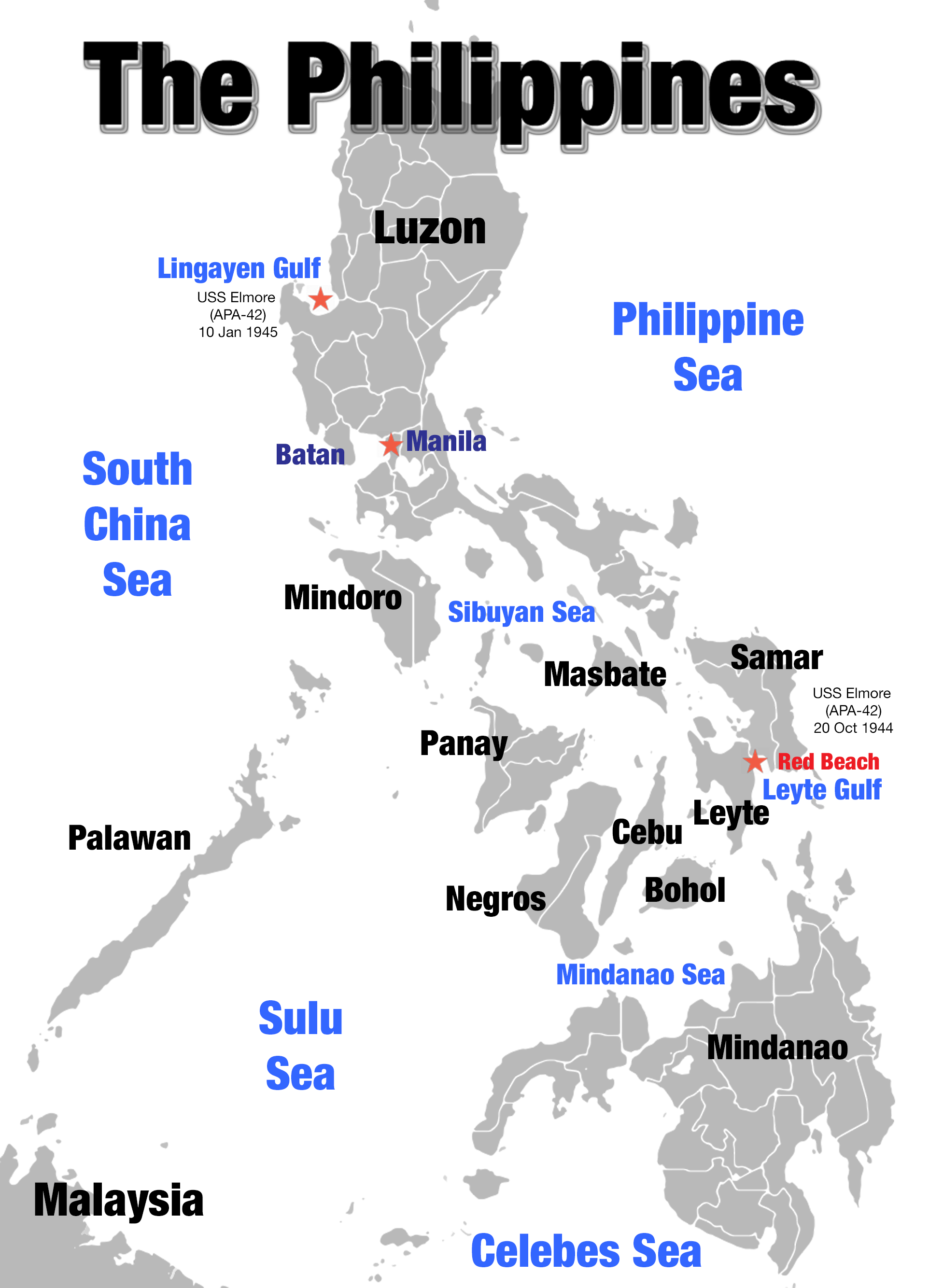

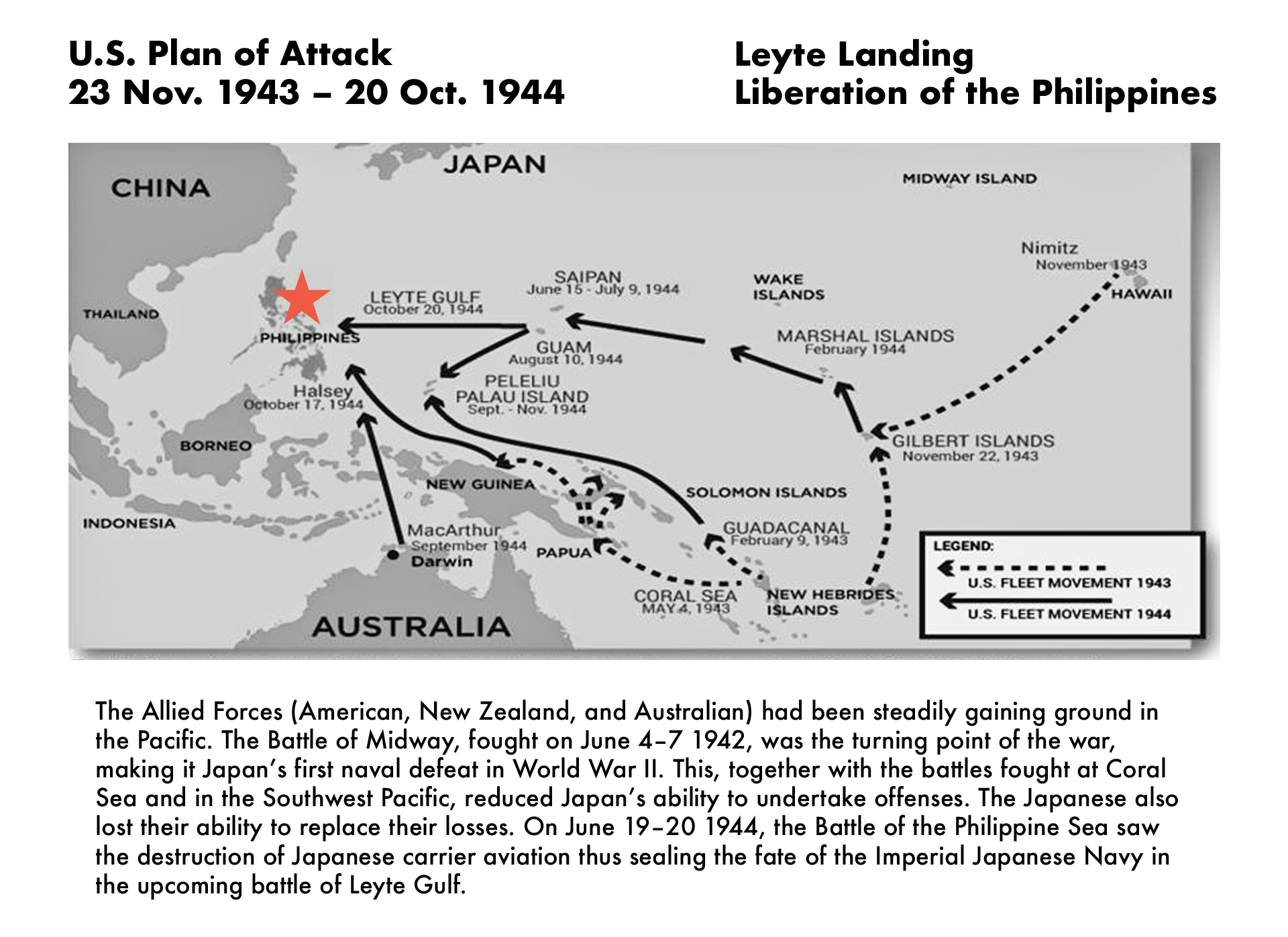

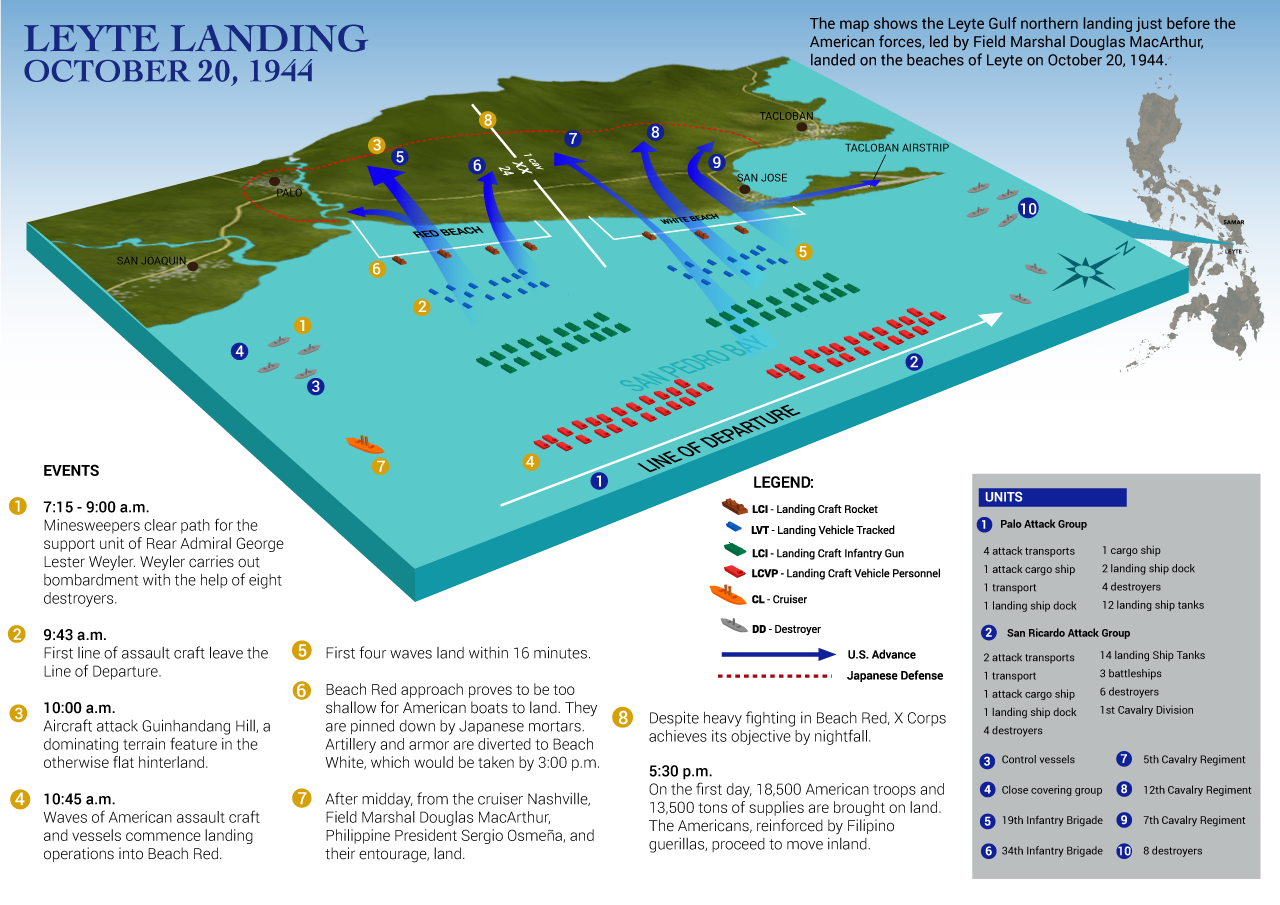

Precisely on schedule, on 20 October 1944, four U.S. Army divisions (1st Cavalry, 7th, 24th, and 96th Infantry) poured ashore on the east coast of Leyte, where strong opposition was met at only one of the four division beaches (“Red Beach”). Leyte, one of the larger islands of the Philippines, offered numerous deep-water approaches and sandy beaches which provided opportunities for amphibious assaults and fast resupply. USS Elmore and other attack transports were critical to the assault plan. Troops had to be landed quickly and safely to insure the success of the invasion.

Japanese aerial counter-attacks damaged USS Sangamon (CVE-26), an escort carrier, and a few other ships but did not hinder the landings. Later in the day, General Douglas A. MacArthur gave his "I have returned" radio message to the Philippine people. Previously, under orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, MacArthur had departed the Philippines by PT Boat in March 1942. By sheer determination, he was back. To the Japanese, if Leyte were to be lost, the rest of the Philippines would soon follow, so they prepared to send five strong naval forces to drive off the American fleet and add more troops for the land fighting. In the following days, this response would lead to World War II's largest and most complex sea battle, the multi-pronged Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Leyte Landing

The landings at Leyte were meticulously planned by the Americans in coordination with Filipino guerrillas, who provided them with intelligence assessments and raw information. Small teams of Americans would also covertly scout the landing areas and the approaches to it in order to ensure that there would be no confusion or obstacles that would disrupt the invasion. Areas were designated for fire support with warships assigned to them in order to prevent Japanese beach defenses and reinforcements from compromising the beachhead to be established by the Invasion forces.

This was an easy landing, compared with most amphibious operations in World War II – perfect weather, no surf, no mines or underwater obstacles, slight enemy reaction. British observers on board a control vessel reported that “at first sight, the landing plan appeared complicated, but as regards the landing on Red beaches, the precision with which they were controlled was good to see.”

However, despite the pre-invasion planning, unforeseen or undetected terrain features and Japanese resiliency led to some losses [see "The Story of Hill 522"]. Some landing ships were grounded due to errors in calculating water depth; while other landing ships were damaged by Japanese mortar fire, despite preliminary naval bombardment specifically designed to eliminate enemy resistance. The Japanese used Hill 522 for a mortar emplacement, targeting Elmore's incoming landing craft.

The naval assault force assigned to Palo's "Red" and "White" Beaches was Task Group (TG) 78.1 (Palo Attack Group), commanded by Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey (USN) and the Embarking Army 24th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General F. A. Irving (US Army). Transport Unit (Transdiv 24) was commanded by Captain T. B. Brittain (USN) and was comprised of the following ships: Attack transports USS DuPage (APA-41), Capt. George M. Wauchope (USNR); USS Fuller (APA-7), Capt. Nathaniel M. Pigman (USN); USS Elmore (APA-42), Capt. Drayton Harrison (USN); USS Wayne (APA-54), Capt. Thomas V. Cooper (USN); attack cargo USS Aquarius (AKA-16), Cdr. Ira E. Eskridge (USCG); transport USS John Land (AP-167), Cdr. Frederic A. Graf (USN); and Landing Ship, Dock USS Gunston Hall (LSD-5), Cdr. Dale E. Collins (USNR).

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Leyte: June 1944 – January 1945, Volume 12 of the History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Edison, NJ, Castle Books. © 1958. Page 134.

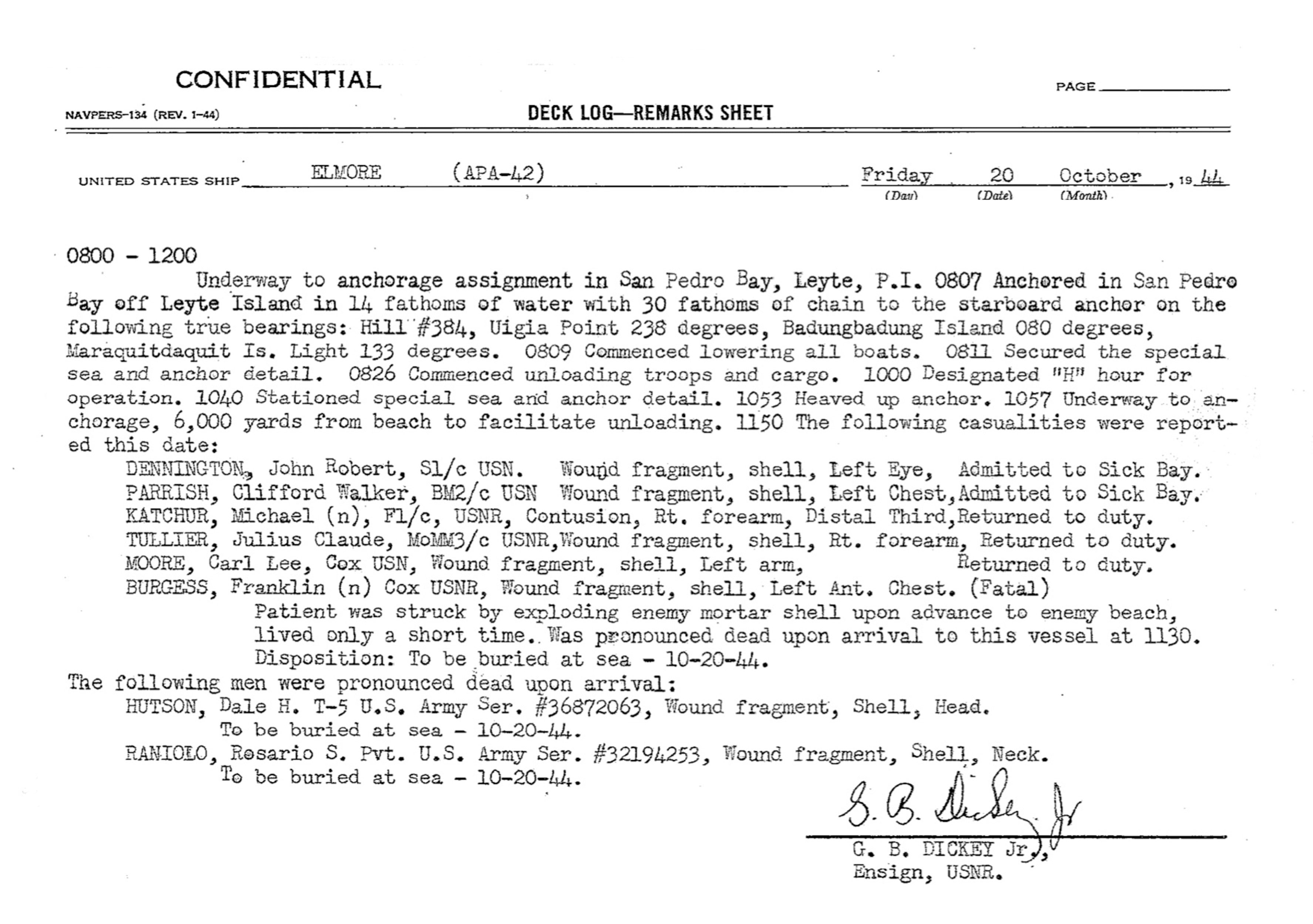

Enemy Action

USS Elmore lost a member of her crew that day: Coxswain Franklin Burgess, from Indianapolis, IN. The coxswain is the person in charge of a boat, particularly its navigation and steering. Burgess' boat was hit by a Japanese mortar shell, and he died a short time later. Two U.S. Army soldiers were also killed: Dale H. Hutson and Rosario S. Raniolo. It is uncertain if all three men were in the same LCVP (Higgins boat) as Burgess. The men were buried at sea later that day from the deck of the Elmore.

Aftermath

The campaign for Leyte proved the first and most decisive operation in the American reconquest of the Philippines. Japanese losses in the campaign were heavy, with the army losing four divisions and several separate combat units, while the navy lost 26 major warships and 46 large transports and hundreds of merchant ships. The struggle also reduced Japanese land-based air capability in the Philippines by more than 50%. Some 250,000 troops still remained on Luzon, but the loss of air and naval support at Leyte so narrowed the Japanese army’s options that they now had to fight a passive defensive of Luzon, the largest and most important island in the Philippines. In effect, once the decisive battle of Leyte was lost, the Japanese gave up hope of retaining the Philippines, conceding to the Allies a critical bastion from which Japan could be easily cut off from outside resources, and from which the final assaults on the Japanese home islands could be launched

Philippine Liberation Medal. The decoration was presented to any service member, of both Philippine Commonwealth and allied militaries, who participated in the liberation of the Philippine Islands between the dates of 17 October 1944, and 2 September 1945.

Sources:

• Wikipedia

• Morison, Samuel Eliot, Leyte: June 1944 – January 1945

• https://history.army.mil/brochures/leyte/leyte.htm\

• The Leyte Landing, Philippine Presidential Museum and Library